Abstract versus representational painting: here are some some thoughts on this topic by Eric Kandel, an old colleague of mine, and Sarah Mack.

While artists are now wondering whether they are doing something important, scientists are all talking about art – Margaret Livingston, V.S Ramachandran, Robert Shapley and, as discussed here, Eric Kandel. Neuroscientist have invented the new discipline – neuroesthetics. This trend of neuroscientists getting interested in the arts reminds me of an earlier trend when molecular biologists, such Francis Crick, switched to the neurosciences.

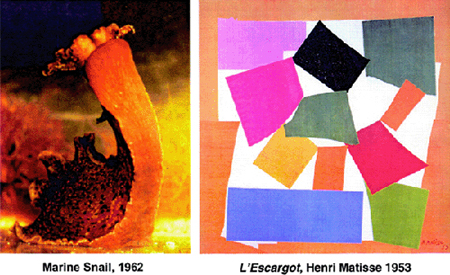

Eric Kandel with his interest in learning and memory, studied a form of learned fear, in Aplysia, a seaslug, for nearly three decades.

Subsequently, he verified that the biological principles discovered in Aplysia also hold true for the mammalian brain: A seaslug with only 20,000 neurons stores its memory as we do with our estimated 100 billion neurons.

In his article, Eric Kandel argues that a reductionist approach is not only fruitful in science, as in his case, but also in art, taking J.M.W. Turner and Mark Rothko as examples.

Turner, early in his career, portrayed ships realistically as seen in Calais Pier: an English Packet Arriving (left picture). In contrast, his later paintings of ships in stormy weather were highly abstract, e.g.: Snowstorm: Steamboat off a Harbor’s Mouth (right picture).

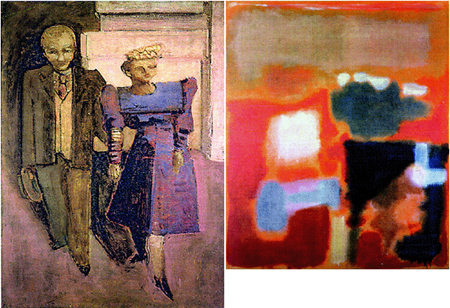

Mark Rothko, Eric argues, is an artist who takes this reductionist approach even further. Rothko’s early work in 1938, he judges to be figurative and fairly unremarkable (left picture). But, Eric suggests that Rothko’s work in 1948-49 shows that the human drama, which is evident in the painting, now has become detached from the human form (right picture).

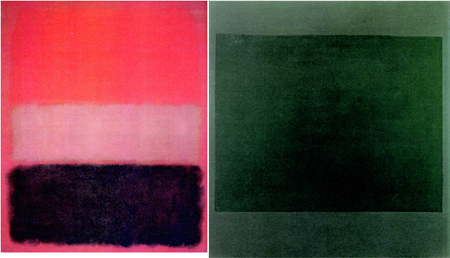

In the fifties, Eric continues, Rothko limited the number of forms and colors even further (left picture) until, in the sixties, he says, the reductionist approach is taken to the extreme by the artist shifting his focus from contrasting colors to the absence of colors (right picture).

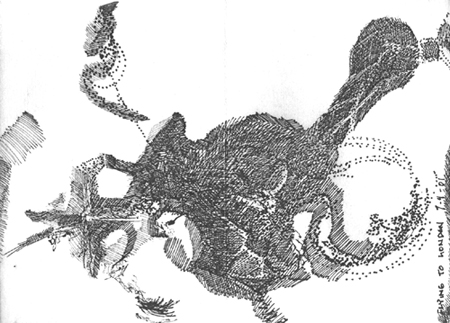

Interesting is the final picture in Eric’s article, a pen and ink drawing on a scroll by Jean Magnano-Bollinger, undated.

Eric now suggests that a reductionist approach in art may serve to forge a bridge between art and science:

Much as Leonardo and other Renaissance artists used the revelation of human anatomy to help them depict the human form in a more compelling and accurate manner, so contemporary artists are likely to benefit from insights into brain processes that inform them about the critical features of emotional response. Indeed, some artists who are intrigued by the workings of the mind have attempted that already. One such artist is Jean Magnano-Bollinger, who uses pen and drawings on a scroll to record what is going on in her own mind. She seeks a direct communication between brain and paper, without the intervening processes such as feelings, sensations, and aesthetic judgments.

Jean Magnano-Bollinger herself says

“The most important note about these scrolls is that they were recorded with my eyes closed. They were not drawn to create art; they are recordings of my attempts to understand process and movement of mind to focus as deeply as possible on brain.”

What Jean Magnano-Bollinger does sounds like fun. However, the late pictures of JMW Turner and Mark Rothko, shown here by Eric, are sad choices for illustrating the power of a reductionist approach in art. I see the mental decline of both of these artists manifested in these late paintings. It is tragic that these two great artists sacrificed their lives to reductionism.

In my opinion, better examples of the power of abstract art are seen here on A&P. David Palmer, MJ Illingsworth and Syau-Cheng Lai express a beauty in their abstract paintings that reminds me of music. Rather than making me feel dissolved into misery, as the late Turner’s and Rothko’s do, these contemporary examples of abstract art convey to me a joy of life.

In contrast to Turner and Rothko who did not or could not return from abstract to representational art, Eric Kandel applied his findings from the seaslug to the complexity of our limbic system, our substrate for learned fear.

Wouldn’t his scientific approach be akin to going back and forth between abstract and representational art?

I guess I will need some more time to digest and comment on this post as it makes me think a lot, but I have to say that I am honored to be in the company of people like Birgit who count the great Kandel as an ‘old colleague of mine’. I vicariously followed his adventures with the aplysia in his latest book and I remember loving every bit of it…

Birgit,

There are several interesting threads one could take up here. I certainly think some artists have pursued abstraction and simplification to try for a certain purity of expression. According to some exhibit text at the National Gallery about Rothko

I don’t know whether Rothko was simplifying partly in order to “study” color phenomena, or if his goal was just maximum impact of his color.

An example of an artist apparently adopting methods of experimental science is Mondrian. When taken to task by someone for painting over his canvases, he replied: “I don’t want pictures, I just want to find things out.” Like Rothko, he went from more figurative early work to very simple, abstract forms. Of course, the idea of making experimental studies to try something out is used by perhaps most artists to some degree or other, and doesn’t necessarily relate to either science or abstraction. I guess once could say that idea/hypothesis-trial-error-repeat is a method for learning that one can use in any field.

Yes, I agree with you on the view that Kandel’s approach switches from classic reductionism (when he developed a working theory of memory using single neurons of the aplysia) to wholesome representation (when he and other researchers like Joseph LeDoux are using the principles understood using reductionism to explain fear/emotions using models involving large scale neuronal ensembles).

I believe that what we perceive is not just an upstream flow culled of individual neurons working in concert but also a downstream flow of stored experiences and dispositional states that influence individual neurons to act in ways they do…

That said, I have not seen much of this two way traffic in art. In most cases, artists tend to switch from a very representative ‘realist’ format to a reductionist ‘abstract’ format and never the other way around (like you have pointed out). I have always wondered why… Of course there are others who have stayed the course throughout their lives (like Chuck Close).

On A&P, I like Mark Illingsworth work that seems to straddle abstract ideas and shapes with representational forms (I think I called it meaningful abstraction)…

I like the snail and the Turner, though I have always preferred his simple and airy watercolors.

In the case of my own photography, abstraction seems to come in two guises. In the totally non-representational color work I mentioned on Sunil’s post yesterday, aside from just inexplicably loving the abstract patterns, I am curious about how the forms and colors create that attraction. But I suspect that anything I learn from this will not carry over much to the rest of my work.

On the other hand, as Karl commented recently, I also like a lower level of abstraction to achieve what I want with my “realistic” work. This may be similar to what representational painters do when they’re deciding how realistically detailed to make their pictures.

Birgit,

I wish you would clarify what it is you see in the work of Palmer, Lai, Illingsworth that you don’t see in the later Rothko and Turner. Certainly, Rothko adopted a severely rigid compositional format. The work of David et al. is more lively and varied, to be sure. But I don’t see that issue in Turner.

I like Bollinger’s drawing–would love to see more. You might also be interested in the artists from this show. I will be traveling to see it soon.

Very interesting concepts. Whereas representational art is more broadly accepted and contains objects of association, abstract art does have merit.

It is indeed interesting that Turner and others recognized the power of form and color all on their own.

Science should definitely explore the effects and nature of abstract art. We already know how music can so profoundly affect moods. Why wouldn’t images?

Arthur,

Those are fascinating artists, I like all I’ve looked at so far. Slavick echoed one of David Palmer’s ideas about his work, with her “ambiguous scale so these systems equally resemble an aerial view of a city at night or a microscopic view of organic matter.”

I also find the Bollinger very interesting.

The whole “ambiguous scale” thing appears to be something of a trend. See, for example, this show.

An exciting trend.

Following up on Steve’s first comment,

I guess once could say that idea/hypothesis-trial-error-repeat is a method for learning that one can use in any field

when I first read the article, I wondered whether it was making a contribution to the arts. The paper was originally presented at a symposium ‘Perception, Memory and Art’ held at the inauguration of a president of Columbia, 2002. Half of the paper deals with science, the other half with art. Perhaps, the art was a way of providing pretty pictures for a research story. Perhaps, the art discussion was a compliment to Columbia’s new president whose wife is an artist.

But then, I started thinking about as Sunil says I have not seen much of this two way traffic in art . I also began to wonder about the message of the article because the scientist, praising reductionisms in art, himself is using both a reductionist and a ‘holistic’ approach.

What prompted me to do finally do this post was Steve’s interview of David in which David considered the possibility of going back to painting people.

As David pointed out there are painters who go from representation to abstraction, or vice versa, besides Richter a few I can think of are Diebenkorn, Jennifer Bartlett, and David Hockney

Perhaps now, there is more fluidity, a greater exchange between abstract and representational art. From what Steve says in his comment#5, I get the sense that in his photography, his representational work profits from his abstract work (even though he himself questions this).

Suppose that up to recent times, there really has been a largely one-way street from representational to abstract art and that this one-way street was promoted by great artists at a cost? Suppose, Turner, in seeking more and more light for his pictures, was compelled to grab more and more for the bottle until his diet reputedly consisted solely of rum/gin/milk? That seeking for his holy grail brought about his mental decline?

And Rothko, of whom Kandel says: “In the 1960ties Rothko takes the reductionist approach to the extreme. His focus shifts from contrasting colors to the absence of colors – the black canvas. …In spite of the work’s radical simplicity, viewers consistently invoke mystical, psychic, religious references to describe Rothko’s effects.” Psychiatrists, other than Kandel, speculate on Rothko’s state of mind. http://www.pep-web.org/document.php?id=jaa.030.0017a. Wouldn’t one assume that an artist, as a result of mental decline, would lose the ability to utilize his/her original skills?

The question that I am raising is whether the huge embrace of abstract art in recent history could have been prompted by disease? Did a few great artists of sick mind inspire the fashion of abstract art? And whether the more natural state of artistic expression is a-going-back-and-forth between abstract and representational art?

Birgit,

I don’t buy the disease hypothesis. More likely, in my view — and I’m not as well versed in art history as I would like to be — is that the advent of photography shocked many painters. In particular, the previously unique ability of painting to capture a scene was surpassed by photography, with the important caveat of color. (Color photography was actually possible early on, but the process was difficult and the results unimpressive.) I think this had a lot to do with painters moving toward abstraction as something they could still do better. Plus it was a great way to rebel against the past.

Curtis,

You have some interesting thoughts and paintings on your website. Are there particular ideas or emotions you want to express that are better suited to an abstract approach? Does it just feel more natural to you?

The question that I am raising is whether the huge embrace of abstract art in recent history could have been prompted by disease?

I fail to see how. It may very well be that individual individual modern artists were neurologically abnormal—although not necessarily in a pathological manner. But such abnormalities would presumably not be any thing new for the human species. Probably all great artists are abnormal in some way. Abstraction took of when it did for historical-cultural reasons and not biological ones (or at least so it would seem).

And the very idea is offensive, reminiscent of the Nazi idea of modern art as “entartete”(degenerate). (It also suggests the contrary but equally problematic idea of romanticizing mental illness.) Of course, this doesn’t matter so much if you have a rock-solid case. But you don’t, you’re just speculating. So, at the very least, you need to seriously qualify what you’re saying.

And I think that aesthetic theories based in neuroscience (or evolutionary psychology, or what have you) would be a lot more credible if they would avoid facilely labeling certain artistic approaches as more “natural” than others. A general aesthetics needs to do justice to the broad spectrum of human creativity, which has manifested itself in an incredible range of activity.

Brigid,

Disease?

Abstraction certainly has firm roots in Thinking (William James, etc.) and is, I think, consistent with our modern sensibilities.

deKooning?

Steve,

Adding onto what you said, the rise of photography, absinthe and the engine of the industrial revolution all contributed large parts to the development of abstract art. Established painter brains atrophied by liquor also helped.

Arthur,

of course, I am speculating. I am posing questions for you people, the artists and scholars of art.

You are wrong in claiming that I said individual artists are neurologically abnormal. Instead, I speculated whether a few afflicted great artists might have inspired a trend towards abstract art.

Also, clearly, I cannot possibly find abstract art ‘entartet’ having professed a great liking of David Palmer’s and Mark Illingworth’s art.

I am surprised that you equate ‘modern’ with ‘abstract’. Isn’t abstract art quite old by now?

On a personal note, growing up in postwar Germany, I suffered intense guilt feeling about the country’s Nazi history. Perhaps, this guilt prompted me to marry a Jewish man whose parents were communists?

What about abstraction as an expression of Inablility, with or without the booze?

Birgit,

I’m not calling you a Nazi; I’m saying that when you make claims like these in such a casual manner, these ideologies are invoked. You’ve brought forth the idea of abstraction in art as a symptom of pathology, and like it or not, this notion has some unpleasant associations.

Its exceedingly doubtful that the cognitive excentricities of a few artists would lead to a large-scale shift in aesthetic sensibility in the absence of broader cultural shifts. This is why the later more abstract work of Turner (and Goya, and others) failed to permanently upset a mainstream sensibility dominated by the likes of David, Ingres and Bouguereau. When the likes of Monet, Kandisnky, and Mondrian came along, they were connected with larger social-cultural movements. These movements are what tipped the balance, ultimately. And whatever the artists’ “afflictions”, they were also by and large smart, rational thinkers, which is what gave them such influence.

Modernism in art is widely associated with abstraction, be it partial like Turner’s or more extreme like Mondrian’s. When people talk about things like post-modernism, they’re often talking about a turning away from abstraction as ideal.

John Lennon:

The basic thing nobody asks is why do people take drugs of any sort? Why do we have these accessories to normal living to live? I mean, is there something wrong with society that’s making us so pressurized, that we cannot live without guarding ourselves against it?

i’m always intrigued by how rothko didn’t call himself an abstract artist:

“I am not an abstract painter. I am not interested in the relationship between form and colour. The only thing I care about is the expression of man’s basic emotions: tragedy, ecstasy, destiny.”

it’s also fascinating to me how once artists step away from representational to abstract, they never did go back. love this discussion/questions raised…

Very interesting quote, Jenny. I guess abstraction to Rothko meant academic, removed from human reality. I think for most people it is used in about the same way as non-representational or non-objective.

it seems ironic when we see it now, that he would refuse to call himself an abstract artist. but i can see why he wouldn’t want to have a label fit on him, if most of his work was to eliminate the historical content of art, to ruin the illusion that is offered in representational art. that makes sense to me, if i were fighting to change boundaries and create a movement, i wouldn’t want one put on me either.

and yes, i agree that abstraction, and art in general would be better off without the drugs & alcohol…

i guess with the duo of art and science, i wonder is this an honest creative event? (i would like to think that creativity knows no bounds and reaches beyond the canvas.) abstraction in america seemed to born out of an identity crisis, art today is offering a new identity crisis (the question we all wonder, are we doing anything important?)so will science have an answer for us? so interesting…

Jenny,

I think the label question depends on your goals. If you’re an individual artist just following your own evolution, then perhaps being labeled is not desirable. But it might be good marketing unless the label is quite negative or really doesn’t fit. On the other hand, if you’re hoping to start a movement or a community of like-minded artists, having an appropriate label could be very helpful in attracting people. They would have something straightforward they could relate to.

I think art and science have much more in common than most people imagine, but one of the big differences is that some kind of community is truly essential for the scientist. If your work doesn’t fit in with the rest of your field, it’s simply not science. Of course you may be working out new ideas with new techniques and so on, but the connection is necessary.

But maybe I’m wrong about this, too influenced by the myth of the individual artist. Communities are still important, there are materials and working techniques that are passed on, etc. Is the similarity greater than the difference?

absolutely. i think that with the individualism, loneliness and the lack of community with non-artists is what automatically creates a community with artists! (of any technique, medium, movement, label or lack of.) you’re right though, we have the option to take part in that community, science doesn’t really have that choice, as a practice.

Jenny,

this is breaking into your discussion with Steve and temporarily changing theme:

Reading the links on your website, I learned that one of the first painted rectangles was Malevich’s Black Square. In America, Rothko may merely have further popularized this art form and inspired later rectangle painters – Ad Reinhardt, (middle of 1960s), Mel Bochner’s (‘70s) and Peter Halley (’80s).

I am learning! Should one read up on what inspired Malevich to become a ‘suprematist’? Or, perhaps, it would be more interesting to find out what made so much of the Western world embrace simple geometry?

Again, my background intrudes, the Black Circle was painted in 1915. Other Europeans then also took up painting simple geometric forms – rectangles or circles, and sticks. Perhaps, they were inspired by the large-scale destruction of Europe during the first half of the 20th century into building blocks, sticks, squares and stones.

Very few events have a single cause. In medicine, many diseases are considered to have a multifactorial origin. Must be the same with fashions in art.

wait…birgit, what link on my website?

Steve,

I think that community is pretty much essential in art as well as science. Its true that many artists spend time working alone in a studio, working on individually motivated projects. This I believe is more or less impossible in modern science. But the same lonely artist will also visit the studios of other artists, discuss ideas is coffee shops a bars, show their work in galleries, get written about in newspapers and magazines, and so on. Nowadays, they’re on the Internet. Without such activities—as informal as they are—there is no art, no culture.

But it might be good marketing unless the label is quite negative or really doesn’t fit.

Negative labels are okay. I believe that impressionism, fauvism and cubism all started out as slurs concocted by enemies.

Jenny,

this one

http://www.boston.com/news/globe/ideas/articles/2007/03/04/out_of_the_box?mode=PF

I like sociologist Howard S. Becker’s notion of art worlds

Arthur,

I think you used the right word culture there. I’m thinking that’s analogous to the body of science, in which some theory about biology has to respect the chemistry and physics of the situation. It’s not as well-defined or perhaps tightly connected in culture, but an artist still has to fit in in some way or they practically don’t exist.

Arthur, individually motivated scientists still exist but their professional existences are precarious.

It works the same way in art.

brigit,

well, i can’t really tell you what to read, i just bookmark things that i find interesting, like the petrovich article.

and what a parallel..art is like a disease…i would agree that when it comes to works of art, it would be difficult to declare that there is a single source of inspiration.

reminds me of what lordeit said, “there are no new ideas. there are only new ways of making them felt.”

D.

I have not read William James, probably, because I was not educated in America. But, back In Germany, I discovered his younger brother and read all his novels.

Looking up William James now in Wikipedia, I learned that he too had periods of depression and even attempted suicide.

And you mentioned de Kooning.

As Wikipedia says about de Kooning

..there is much debate over the relevance and significance of his later paintings, which became clean, sparse, and almost graphic, while alluding to the biomorphic lines of his early works. Some say his mental condition and attempts to recover from a life of alcoholism had rendered him unable to carry out the mastery indicated in his early works, while others see these late works as prophesizing the clean, surface-oriented painters of the 1990s and 21st century.

It is interesting that ‘abstraction’ in art and psychology can be linked with depression and alcoholism.

Brigit,

WJ?

Here is my favorite WJ story:

WJ was teaching Philosophy (Pragmatism) at Harvard and really did not like it so much: rules, pretensions, etc. He was told that he had to give a final exam which seemed ridiculous to him and absolutely contrary to his thinking/teaching.

Gertrude Stein was in his class and on the day of the final, as it was a beautiful spring day, she decided not to take the exam. Instead she wrote a note to James saying that because the day was so splendid, she was taking a walk along the Charles.

The consequences: She got an A.

deK?

Certainly deK was losing his facilities at the end (who doesn’t?), but I find no useful connection as it relates to his “abstraction”. For him, it was a continual process over many, many years.

There is a very good biography on deK that came out several years ago. I still don’t like him.

D.

I will read WJ. He sounds like a neat guy.

I very much liked one of deK’s paintings at the Met exhibition, about a decade ago. It was of a mountain side.

Arthur,

The Big Bang exhibit does sound exciting. I hope that you will do a post on it for A&P.

Arthur and Steve,

I have not been able to find out much more about Jean Magnano-Bollinger’s work. Perhaps, Karl can found out more for us when he goes to NYC after his vacation.

Brigid,

You are right. I too have seen deKoonings that I have liked a lot.

And, Jean Magnano-Bollinger.

She peeked. Her temptation is my jealousy of a thought so well-formed.

D.

In the sense of:

Verb 1. peek – throw a glance at; take a brief look at; “She only glanced at the paper”; “I only peeked–I didn’t see anything interesting”

?

I’m doing a full-scale write-up of Big Bang! for another online publication. You can see my related blog post here.

B.

That’s the peek.