‘What one must paint is the image of resemblance—if thought is to become visible in the world. ‘ —Rene Magritte

Semiotics is the study of works of art signs and symbols, either individually or grouped in sign systems that can give us more insight from the work source and meaning. All painters work in a pictorial language by following a set of standards, basics and rules of picture-making. There is a big resemblance between pictorial image making and the creation of written language, the study of this nature of what consists and the individual components of pictorial and written language is known as Semiotics.

Semiotics can translate a picture from an image into words. Visual communication terms and theories come from linguistics, the study of language, and from semiotics, the science of signs. Signs take the form of words, images, sounds, odours, flavours, acts or objects, but such things have no natural meaning and become signs only when we provide them with meaning.

The semiotic theories are not definite but constantly being reviewed, extended and developed to become more precise and improve the significance of the information gathered when these theories are applied to works of art.

Visual Art consumers have become highly sophisticated readers of signs and signals, decoding subconsciously art work compositions. Everything surrounding us human beings today, including our own identities are all moulded and manipulated by signs, words, images and our visual language.

Communication can be a form of mind control; the one that has the power to speak higher and have the right speech can have a power over others in a certain way by making the individual point stand above all. The same happens with artworks with a conceptual meaning that stand and activate other people’s minds.

Different media carries different meanings despite the message content. Each form of media explores these meanings in the way the subject is represented and the context in which it appears. Visual language covers a whole range of different social mediums from low culture advertising, comic books and television to high culture like galleries and theatres. Visual signs look for the possibility of a language that already exists and is used already by a large amount of people connected or not with the arts and the media. The linguistic sign consists of content like sense and meaning of an expression like letters or sounds. Language is ruled by strong codes or rules and becomes complicated when we look at it in the form of visual artworks. It becomes a translation from linguistic to visual expression and the forms are as random as in linguistic signs.

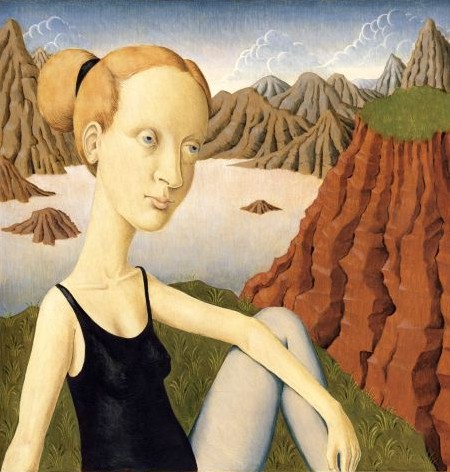

Icons as a form of semiotics are all kinds of pictures representing an object like photos, drawings and paintings. Most pictures have a double meaning; visual and symbolic, conventional and arbitrary. Everyone knows, for example, that a picture of an old woman with a broom it is just a picture of an old woman but it can be perceived as a picture of a witch. Modern advertising is filled with this type of signage that holds double meanings.

Normally it is thought of as language in relation to pictures, very straight forward and clear where the visual language is an expression of emotional, deeper thoughts or even ambiguous ideas. It is then that visual expression needs the linguistic explanation to clear up the superfluous meaning. For example, in advertising, a linguistic message always comes attached to the advertisement in order to help establish the picture being shown.

So this form of anchorage of meaning opens us up to not only one, but several meanings without unsettling the main indented meaning; it forces the mind to interpret the media in a most complex and accurate way.

Pictorial Semiotics is often concerned with the study of pictures into a more constructive verbal description while maintaining confidence in the objectivity of the practice. A linguistic community that speaks the same language is a group of people making verbal agreements, speaking similarly as long the community lasts. Small changes are easily adopted and taken positively and are adjustable. The idea of representation by chance, where things do not follow rules but are used as signs is however very explored in the visual arts. This is where the principles of semiotics come in use; to map out and decode as a discipline.

The paintings of Rene Magritte for example in his series called ‘ The key of dreams (1930)’ show a collection of objects illustrated and labelled just like in a child’s learning picture book. They are all incorrectly described except for one of them. the As another example he paints a standard side view of a head of a horse against a black background with white writings and labels it ‘a door’, all of this with a primary aesthetic. These violations of representation are playing up with our early impingement teaching of associating names with the correct class objects that are part of our visual culture since childhood. Of course we grow up taking this for granted but Magritte with this illustration is showing us in a great way how resemblance, symbols and signs are often just representations of the real things.

Magritte in ‘The Betrayal of Images‘(1929) makes a painting of a simple pipe, a side view well illustrated with the phrase underneath saying’ This is not a pipe’. This text is neither true nor false and explores a new science of representation and signing. Is the painting a pipe or a depiction of a pipe? Yes, it is not the physical reality of a pipe, it is a representation of a pipe, a painting of it, a signifier for it but not the real thing. Would that still make it a pipe or should we call it something else?

Magritte had a special talent to make objects look mysterious and magical, and his objects are carefully chosen and depicted in a school textbook way. The ‘Pipe’ painting is a good example of how conventional imagery often betrays us all by making everyone realize that it is just a convention and not a real object. In my opinion I think Magritte was trying to make us all aware of the signs and symbols we often take for granted in our everyday lives.

This is a classical association for artists to make out the difference between the signifiers and the signified. A sign is something that stands for something other than itself; we interpret things as signs naturally by relating them to familiar systems or conventions.