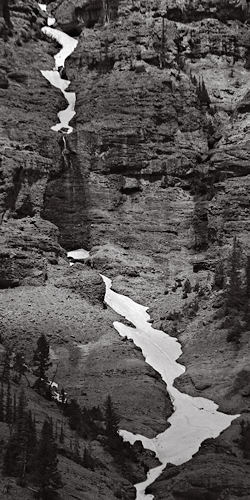

On my last waterfall post, I claimed I had just started making waterfall photographs less than a year ago. But later, going back exhaustively through my files, I discovered the one above from just over two years ago. It show the Lower Falls of the Yellowstone, an extremely popular subject for all kinds of image-making. That would normally be enough to rule it out for me, but there was nobody else around, I had biked 40 miles in freezing temperatures to get there (snow permitting, Yellowstone is open to bikers a few weeks before cars are allowed in) and I wasn’t about to bike back empty-handed.

Viewing the image later, though, I had no idea what to do with it. It didn’t seem to fit anything that made sense to me. I sort of liked it, but couldn’t figure out why. I not only didn’t print it, I never even tried processing it (developing the raw image toward something presentable). So it’s no wonder it slipped from my mind.

I was not only shocked to rediscover it, but excited to have found an image like this from so early (second time around, that is: I had a previous fling in photography followed by a long, long hiatus). It seems a harbinger of my evolution towards flat, abstract compositions reminiscent of Clyfford Still paintings, as discussed before. It is not as flat as later ones. It has a layered spatial organization, but is tending toward flatness in that the layers have very different tonal ranges, making them less related in depth and more like independent shapes.

A few weeks ago I made a rather different kind of image (above), in which I was mainly interested in the broad, varied line of snow going down the crack (the waterfall is mostly a dark, wet patch on the rock wall in the middle). Turns out Still had been there, too.

Clyfford Still, 1949-A No. 2

My most recent waterfall work is influenced by reading Frank Stella’s thoughts on creating a space that is more three-dimensional, especially one that reaches out to contain the viewer. I think the last waterfall from my previous post is more like that. Along those lines, I’m wondering what you think of the following three images of Lost Creek Falls in Yellowstone. In particular, which one or ones give a stronger feeling of 3D-ness? Or put another way, with which do you feel more as though you are a part of the scene? I know it’s difficult to get the right effect from tiny images on a computer screen, but just use your imagination and try your best! I’m not claiming that any of them succeeds at all, I’m just wondering how other viewers perceive them.

I loved the connection between Clifford Still and the frozen waterfall. It is indeed great when artworks complement and contrast one another… With regard to your question, I would certainly say that the last image is the one that captures the essence of the 3-D’ness’ the most… The rocks jutting out from the outcropping make me feel like I am standing at the bottom of the fall getting all wet. I think it is the angle of the third image that gives it this perception. In fact the first image would have much more elements of 3-D’ness’ if shot from the same angle as the third (just looking at the water bouncing off the crags on the face of the rock)…

Steve:

The third for sure. But why? Sunil points out the camera location and the angle. I would add a vote for the “spring” of the water.

Your waterfalls make me want to categorize. I can see at least three significant aspects of a waterfall as such: The line of release where the water abruptly changes direction, the veil or drop as the water falls freely and the splash. Perhaps they can be thought of as the pop, drop and plop.

In the first image, the springing effect is graphic in that the river is making a bee line for the precipice and it doesn’t appear to carry as much water as is falling over the cliff. Suddenly the waterfall announces itself as a pronounced increase in volume. Furthermore, the snow and ice conspire to redistribute the orderly stream into a complex of veils.

The falling water then fans out into a mist that merges with the snow and ice banks below and the tightly channeled water becomes a ghost. I love it. The stream cannot be Still when flowing Cliff ward.

From a mysterio perspective, it would seem that a waterfall image is best served when one of the “p”s is left to the imagination.

Jay,

You sure know how to play with the words..

“The stream cannot be Still when flowing Cliff ward”

Loved it.

Yes, Jay is too funny. I only tolerate him because he’s so creative in the other thoughts be gives us. :) I love his description of the first picture. Jay, will you write the text for my book?

You both make a good point about the role of the water stream jutting out toward the viewer, which makes a lot of sense. For some reason, I had been thinking more in terms of the architecture of the rock cliff and the degree to which it wraps around toward the viewer.

Steve,

At last, I figured out why I lack affinity for Clyfford Still!

In ‘Creative Perspective for Artist and Illustrators’, Ernest W. Watson writes that

(Sorry to bore you sophisticates with elementary facts of art history, but I am on training wheels).

The Clifford Still, shown here, looks flat compared to the perspective in your beautiful waterfall pictures.

Being fascinated by perspective, of course, I am bored by C.S.

Birgit,

I don’t especially “like” Still either, though he is definitely growing on me. And I’m certainly not trying to imitate his style, along the lines of Cennino’s recommendation. But I keep finding that shapes and relationships that I do like are ones that he has also explored. I’m not sure how significant it might be, but I’ve become increasingly curious about his work. I guess I’ll have to make a piligrimage to his Denver museum when it opens.

Steve,

At what distance do you shoot your waterfalls?

In ‘Basic Perspective Drawing’ John Montague claims that a normal view is achieved with a 60 degree cone of vision. Do you use telephoto or wide angle lenses or do you aim for a ‘normal view’?

After J. M.’s illustration of how objects are flattened out using a telephoto lens, I will be more alert to that issue when I shoot the dunes.

Steve:

And what book might that be?

Reminds me of a Rauschenberg book that came out some time back. Robert had disapproved of the text, but must have lost out to the publisher. The compromise was to print the text in gray ink on gray paper and with the busiest prints interposed as a backdrop.

By the way, the image of the snowbound ravine interrupted by the drop off is terrific. The effect of gravity on water is inferred very nicely.

Birgit,

I don’t remember about the first one (I can check later), but the last three were all with the standard kit lens, 18-55mm. The focal length must vary, but it’s not telephoto or very wide angle. The second one, unfortunately, was with telephoto. The creek was pretty high, fast, and cold. I took my pants off and started to ford it, but it looked like I’d have to take off everything and risk ruining my camera if I lost my footing.

Jay,

Like the Beatles, I’ve got no book and it’s breaking my heart. But I’ve got a writer and that’s a start. Baby, …

sTEVE:

Ah…that kind of book.

Steve,

To respond rather late to your query, the last photo is definitely the one that makes me feel like I should duck out of the way. And admire the change in texture between the water and the rock. And also admire the astute comments of others about this blog.

Birgit, Steve’s photos are the exact opposite of your dune path leading over the hill to the lake — that photo leads us right into the depths. Steve’s makes us jump back out of the way.

Steve,

There is a picture of me when I was a kid in a yellow slicker on a boat (Maid of the Mist) getting soaked by the spray of Niagara Falls. I like that picture because it reminds me of so much: my family, our vacations, the hotel, the pool, the fear, the long line, the thrill, the smells, the roar, the coolness on a hot day, etc.

I like these photos because I can think of you: alone on your bike, a long-ride in the cold. The dimension of Life.

D.,

Perhaps the more we like an artwork or any object, the less the reason lies within the work itself.