This post began life as a musing on Robert Irwin’s not permitting reproductions of his (abstract) paintings, detailed in a statement in the catalog of his recent show in San Diego. The catalog, of course, is loaded with photographs, including ones of his early paintings, though many could be considered installation views rather than “reproductions.” (As far as I can tell, Irwin has less objection to photographs of his more recent work, despite its contextual and perceptual nature, seemingly much less representable via photography.)

But then I started wondering about the broader question of our willingness to settle for imperfect, incomplete, and often unsatisfying versions of works of art of all kinds: paintings, sculpture, music, theater, and yes, even photographs. Don’t we constantly tolerate inferior prints, recordings, performances, etc? Indeed, how could we live without them? How would we even learn enough to develop an interest in the originals?

I can understand an artist wanting to control encounters with their artwork, but isn’t contempt for inferior reproductions also a sort of contempt for the viewer or listener? Can’t we be trusted to realize that, say, a Rothko is a much greater accomplishment than it appears in that little jpeg on the web?

How far are you willing to descend in accepting low-quality versions of high-quality art?

HI Steve,

I’m not sure about how far I would descend — seems to me that if you (I mean me) show your (MY) work on the web, you’ve (I’ve ) probably already made the descent — lower than that, it’s difficult to go.

I remember a college professor of mine, early 60’s, saying that she would not listen to music on records. Her reasoning was that the musicians got to edit out all human imperfections when they recorded — they could record over and over until they got it precisely as they wished — and that ruined it for her. She wanted to fully human experience.

I’ve pondered that a lot since then. Now, of course, we can listen to 10 different versions of Weber’s Concerto for Horns over a span of a day or two and appreciate all of them in different ways. It’s unlikely that any of us could hear 10 different versions in concert halls and appreciate as fully the differences in orchestra, performers, conductors, temperament of the hall. And then it would take years to accumulate the 10 experiences and I for one don’t have the memory to hold so much over so long a period of time.

So I have to think that the professor was not just a luddite, but more simply wrong. What a host of delights she was refusing to indulge in in the name of a strange kind of purity.

And likewise, it seems unlikely that I will ever get to Holland, and so will not see much of Rembrandt in person. Should I deprive myself of his work because I won’t stoop to reproductions?

I’m not sure about “contempt,” Steve, but I think the world of thinking about art suffers when art is available only “in person.” At least, my thinking would be impoverished if I couldn’t see even poor reproductions. And too, once in a while, even a web view overwhelms me, stops me cold. Should I deprive myself of the possibility of that happening in the name of purity? Or deprive others…..?

…Robert Irwin’s not permitting reproductions of his (abstract) paintings…

Perhaps, he does not readily identify himself with his early work?

Irwin’s statement:

My interpretation is that, according to Irwin, the unmediated experience of such art is essential. A reproduction on a page or screen is so different it negates the point of the art, and can only be for the purpose of “expediency” (Irwin’s term).

June, I agree with you whole-heartedly. I think it’s very important to settle for less than perfection in most things. Sometimes we may forget how much better being at an actual performance, before the real painting, or in the cathedral itself can be. But that doesn’t mean we should do without the lesser versions.

“Contempt” is too strong a word for Irwin’s case, though possibly it might better fit Clyfford Still, who also kept much of his art out of public view, and sought to control what he did give out. I don’t mean to denigrate an artist’s effort to get the best presentation of the work, but I think it’s counter-productive if taken too far.

I think there’s a difference in photographing Irwin’s paintings, many of which cannot be appreciated at all in an inferior reproduction, and photographing his installations. With the latter, I think the photographer can convey something about their experience (and about others’ experiences) that I imagine Irwin would find valid and valuable. I would really like to know what he thinks of the catalog and publicity photographs.

Steve,

The situation is worse than Irwin describes. Merely inserting a piece of glass between a painting and the viewer is destructive.

Two decades ago, I very much enjoyed a Rembrandt, his 1928 Self-portrait. Five years ago, I found it to be covered with glass. It no longer appealed to me.

It makes for variety that the artist discussed here features himself as an elitist. Inner city children will not find his paintings reproduced in their school books.

Steve sometimes photographs and prints can make some works of art more interesting and actually look better… it can work the other way too!

…isn’t contempt for inferior reproductions also a sort of contempt for the viewer or listener? Can’t we be trusted to realize that, say, a Rothko is a much greater accomplishment than it appears in that little jpeg on the web?

I’d have to say no to the first part, and that the second isn’t the issue Irwin seems to be concerned with.

Some kinds of work, I think, translate pretty well, even in poor reproduction, and others get lost no matter what the quality of the photograph or recording. I’ve been looking at reproductions of Italian Renaissance paintings my whole life, and I finally got over to Italy a couple of years ago to see them in person. It was amazing to be able to get right up next to the Raphaels and the Pieros, but I already was pretty familiar with the paintings through the reproductions. On the other hand, I had seen a photo of one of Irwin’s disks years ago, and couldn’t even figure out what I was looking at. It totally misrepresented the experience of the work, and if I hadn’t already been fascinated by his thinking I would never have bothered to seek out the real piece. It isn’t so much that it was a poor photo, but that the piece is kind of unphotographable.

So I think the call about whether to allow something to be reproduced or not is personal, and is specific to the work itself. I have a wonderful book from the Getty documenting the design and creation of the gardens, and Irwin seems to have had no problem about allowing the many photographs in the book to be published. Seeing the photos isn’t the same as being in the garden, but they at least give a fair representation of what’s there.

As to the second point about the Rothkos, I don’t believe the issue is measuring the greatness of the accomplishment, but deciding whether the reproduction communicates anything of value about the experience of the original. If anything, I think Irwin’s decision not to allow photos of certain pieces shows a high regard for his audience. He doesn’t want them to be mislead into thinking they’ve seen something that they haven’t seen.

Angela,

This is interesting. Can you think of an example or describe something you’ve seen that looked better with — I’ll call it “interference” because I can’t think of a better word.

Steve,

I’m very grateful for reproductions — my life has been greatly enriched by access to things I wouldn’t otherwise be able to experience at all. Of course, “ain’t nuthin’ like the real thing, baby” but something is better than nothing and I’m grateful for it. (Maybe not, though, for Starry Night coffee mugs. Poor Vincent. On so many levels, poor Vincent.)

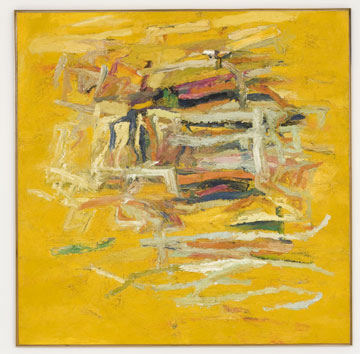

Confessions: I didn’t quite “get” Vermeer (I can hear all the cries of “Philistine!!” even at this distance) until the road show 10 or 15 years ago that pulled most of them together in one place. Many of the paintings are tiny, and something about the scale of them — and, yes, the light, the light, I know, the light — was profoundly moving. Similarly, I resisted Pollack but one day at the Whitney, I decided “I’m going to stand here until I get this.” Again, I think it was the scale of the piece (humongous) that afforded a way in, but I did get it or, at least, I got something that moved my inherent skepticism closer to appreciation. That experience opened me up to the Ab Exes in a way that wasn’t possible before. I had always thought it was a kind of fraud, but in that protracted moment of getting the Pollack painting, I understood and continue to understand that these people really did think about what they were doing, they really were and are after something. I still may not like the work from my personal notions of aesthetics, but I’m more willing to engage with the work. So I start with books and such and then try to see things in person when I can.The repro experience allows the viewing to be more intellectual than emotional, and that can be useful.

So there’s a kind of echoing forward and back in the reproduction experience — studying reproductions lets me know what’s out there, seeing whatever I can see illuminates the repro, and then the repro is enriched by and recalls the live experience.

But also, one of my favorite painters is Whistler. He was an extremely interesting artist, but a profoundly bad chemist. Many of his paintings have not aged well because of the extent to which he corrupted the paint with thinners and because he scraped down and painted over so many times. When I look at those works, I know I’m not seeing what the artist intended and that’s another layer of involvement in the experience of seeing them. To answer my own question, this is one artist for whom repro sometimes is kinder than the in-person experience.

He doesn’t want them to be mislead into thinking they’ve seen something that they haven’t seen.

David, that’s a very nice take on Irwin, but I’m not sure I can go along with you completely. Perhaps part of the issue is the way photographs might get separated from words. A photograph of a disk, for example, would mean very little by itself. Even together with the descriptions I’ve read, it’s difficult to appreciate. But the point is, I can tell that I’m not fully appreciating it, yet I can still see enough to understand the basic concept and its originality, and to be very motivated to view an original. Likewise with his dot or line paintings: anything less than a large, high quality photograph will dramatically misrepresent them. But again, having a description together with a mediocre photograph (and a detail) allows me to construct an inadequate but still entrancing idea of one. Why should I be denied this opportunity? True, I might cast a cursory glance at photo only and conclude Irwin’s a fraud, or the idea I’ve constructed might be a great distortion of the real thing. Why should that bother anyone?

I’m playing devil’s advocate here, and I certainly don’t mean to pick on Irwin in particular: he’s just a convenient example whose work I love. And I do understand about being bothered by what others think. I often cringe at how even my digital photographs–an art form as fitted to the Internet as any can be–come across on an average or even an outstanding monitor screen. Artists tend to be acutely aware of shortcomings even in the original, and that may be one reason it’s difficult to let one go.

I agree that reproductions can sometimes look better–especially if the painting is spatially strong but is perhaps weak on paint-handling or color. The arrangement of forms takes precedence in a smaller, even thumbnail form, so if the paintings’ organization of space is its best element, it will look good small.

This reminds me of an exercise I thought up for a visual artist. Draw a ½ inch by ½ inch box with a pen. Then, fill the box with forms–but make it interesting. This is very difficult because you can’t work with nuance, texture, etc–just a fat penline in a small space. Do about ten of these and you’ll see both how limited an artist’s choices are in terms of overall forms, and how interesting a little box can be.

McFawn,

This exercise is very appealing. I’m working on a series in the form of 12-inch squares and the challenges of the format and the relatively small size grow larger the more I explore it. My thumbnails for the series tend to be about 2×2; 1/2 x 1/2 is very intriguing. Thanks for the idea.