My ongoing look into Japanese and Chinese painting has turned up a few new/old ideas, and blown me away with some new discoveries. It’s becoming quite clear why I felt attracted to it; these are themes I’ve written on before in the context of my own photography (e.g. here and here).

My ongoing look into Japanese and Chinese painting has turned up a few new/old ideas, and blown me away with some new discoveries. It’s becoming quite clear why I felt attracted to it; these are themes I’ve written on before in the context of my own photography (e.g. here and here).

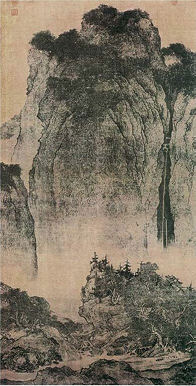

The first idea is about the level of abstraction frequently present. Many of those mountains and rivers seem as much about shapes and textures as about landscape, more evocative than representational. Sometimes there’s an interesting mix of broad abstraction and realistic detail, as in the thousand-year-old Travelers amid Mountains and Streams by Fan Kuan, shown at left.

A second realization is that, like similar works at different times, this one by Fan Kuan smacks of the sublime. This is evident in the language used to describe it by historian Patricia Ebrey (Cambridge Illustrated History of China, or Wikipedia):

Jutting boulders, tough scrub trees, a mule train on the road, and a temple in the forest on the cliff are all vividly depicted. There is a suitable break between the foreground and the towering central peak behind, which is treated as if it were a backdrop, suspended and fitted into a slot behind the foreground. There are human figures in this scene, but it is easy to imagine them overpowered by the magnitude and mystery of their surroundings.

In an interesting side note, Buddhist concepts led some painters to experiment with random (or “automatic”) techniques. For example, Wang Mo (died c. 805) even prefigured Pollock: he

painted only when drunk. He would spatter ink on a piece of silk, laughing and singing all the while. “He would kick at it, smear it with his hands, sweep his brush about or scrub with it, here with pale ink, there with dark. Then he would follow the configurations thus achieved, to make mountains or rocks, or clouds or water.”

Early Spring, Liu Guosong, 1966

But the most exciting discovery for me was the more recent work of a group of Taiwanese artists that called themselves Fifth Moon (or, less poetically, May). Mainly active in the early 1960s, they married modernist abstraction with classic Chinese influences. One of the Fifth Moon painters, Liu Guosong (old-style: Liu Kuo-sung) had studied and worked in a modern Western style, until he saw in 1960 an exhibition of major Song dynasty paintings: “…when I stood in front of Fan Kuang’s ‘Travel in the Mountains’ for the first time I felt that the mountain bore down on me and I experienced a wave of power rushing towards me.” (There’s that sublime again…)

Running Spring, Liu Guosong

Wintry Mountains Covered with Snow, Liu Guosong, 1964

Much of the earlier Fifth Moon painting, like traditional ink painting, was monochrome. It also often had a strong sense of calligraphy, an important (and abstracting) influence throughout Asian art. Color, though usually muted, became more common later on.

Another favorite Fifth Moon artist is Che Chuang, whose father was, in fact, a famous calligrapher. I don’t have decent images of his earlier paintings, but some of his later ones are shown below.

Bottom of the Valley, Che Chuang

Abstract I, Che Chuang, 1985

In comparison, this 21st century American photographer still has far to go. He’s considering taking a brush with him on his next trip to the mountains.

Steve, you too: taking a brush with him on his next trip to the mountains.?

I really like Liu Guosong. I have been googling his water images.

Steve,

I’ve been working my way through Arthur Wesley Dow’s Composition: Understanding Line, Notan, and Color, and co-incidentally today ran across this: “Abstarct design is, as it were, the primer of painting, in which priniciples of Composition appear in clear and definite form. In the picture they are not so obvious, being found in complex interrelations and concealed under detail. …A picture, then, may be said to be in its beginning actually a pattern of lines. Could the art student have this fact in view from the outset, it would save him much time and anxiety. Nature will not teach him composition. The sphinx is not more silent than she on this point.”

And, in a later chapter: “One uses the facts of nature to express an idea or emotion. …Composition is the greatest aid to representation because it cultivates judgment as to relations of space and mass. Composition does not invite departure from nature’s truth, or encourage inaccuracies of any kind — it helps one to draw in a finer way.”

There’s something in there about the relation of formalism to abstraction that I haven’t quite sussed, but the gist seemed relevant to your post.

Birgit,

A certain number of images are available on the web, but the older ones I like best I’ve only seen in a couple of small exhibit catalogs I happened to find in the library. Liu later turned to more “popular” (for lack of a better term) sorts of subjects, particularly astronomical ones. He was very impressed with moon and space exploration.

melanie,

I find abstraction and composition very closely related in that, as an image becomes more abstract, the composition becomes more evident and more important. I’ve wanted to read Dow’s book, but it’s not available here.

I’m sure you know Dow was a primary proponent of japonisme in the U.S. I also just learned that he made very nice landscape photographs, and was sought out as a teacher by Georgia O’Keefe.

An interlibrary loan might be fruitful…

or a browse at abebooks.com (an antiquarian and used book seller where frequently the postage is more than the book)

Steve:

When all a person hears about these days is “subprime”, it is refreshing to have you refer to the sublime.

If you would, could you describe what the sublime means to you? Is it inherent in things or more a matter of personal reaction? That kind of thing.

Jay,

I like your way of asking the question. So as not to go inventing my own terminology, I think that the sublime has to at least involve some sense of great or even overwhelming power. In my view, it does depend on the viewer’s reaction more than on subject. Perhaps the stereotypical mountain abyss invokes a “sublime” feeling for many, but it could also be a street photograph that captures a powerful moment. I would expect it (but haven’t yet had the experience) viewing a great Rothko. I’d use it for what I felt seeing Michelangelo’s Pietà for the first time.

Some have tried to distinguish the sublime from the beautiful, but to me it’s a different dimension. The two terms might or might not both apply to a given work. I could get an overpowered, sublime feeling from something I immediately recognized as beautiful, or might come to see the beauty in, or might never consider beautiful. (June, is the big open pit in Butte sublime? I think it can be.)

Steve:

Do you think that the sublime would tend to involve something bigger than one’s sense of self? I wonder if Fan Kuan’s painting would so encompass a sense of sublimity if it showed a group of laughing peasants pointing at the distant mountain, thus diminishing it’s remote grandeur.

This last July fourth the City of Lakewood decided to throw everything they could afford into a big boffo finish to the fireworks. It was sublime in a way, as it overwhelmed the senses. But it seems that the sublimical response might be developed from such crass voyeurism to the seeing of eternity in a grain of sand. I’ve tried that and all I could manage was an eon or two.

Yes, June, bet you could roast Babe the Blue Ox in an open pit like that.

Jay,

Generally, the sublime does have to be about something beyond self. This is typically taken as Nature, the infinite, the universe, God, the Tao… But one might broaden it to encompass any “major” realization of connection to something you didn’t think you were or could be connected to.

Steve:

Do you think, then, that Obama may have experienced the sublime when he learned that he was distantly related to Dick Cheney?

From the sublime to the ridiculous. Perhaps that’s a political statement.

Overpowered = sublime? In my life, there were small moments that felt sublime.

Steve, thanks for this post.

I think experiencing the sublime, in nature or in art is being aware of a closeness to mystery, a sense of awe that points to some profound or truthful understanding that isn’t easily processed because it is arresting and catches you off guard.

I think this relates to what you said about a realization of connection.

Your article sounds fascinating. I’d like to have more information about Wang Mo, could you tell me from what book you took that extract?

Thank you!

Valentina,

I read about Wang Mo in several places; he seems to have been influential as well as fascinating. The quote is from “Three thousand years of Chinese painting.” by Richard Barnhart, Yang Xin, Nie Chongzheng, James Cahill, Lang Shaojun, and Wu Hung. You can read part of it on Google by following the link from Wang Mo’s name.

Steve, say a piece by Chuang Che at an estate sale, and it set off a whole new direction of inquiry. Thanks so much for your piece.

Steve, saw a painting by Chuang Che at an estate sale, and it set off a whole new direction of inquiry. Thanks so much for your piece.