Just a few miles along the Newfoundland coast from the kelp of last week is the Cape St. Mary’s Ecological Reserve, a haven for sea birds of nearly a dozen main species. Most were gone by mid-September, but there were still many thousands of northern gannets, graceful birds with gold-dusted heads and necks, and a nearly six-foot wingspan.

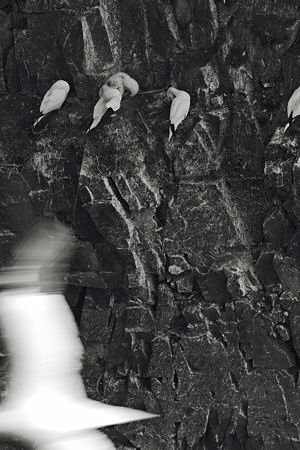

The gannets cover Bird Rock quite thickly, amounting to several thousands on this single sea stack. Viewers can see them from across a narrow gap, and the birds seem to pay no mind at all. Greater numbers nest on neighboring cliffs that are less isolated, though still protected by the reserve. Despite the density, the gannets manage to find their nests even when returning after a year. By the way, if you look closely, you’ll discover some dark-feathered birds in these images, sub-adults (less than four years old) that have not yet attained mature coloring. Not being a birder and this not a birding blog, I’ll spare you most of what I learned from our knowledgeable official guide, Chris, who also happened to be our B&B host. I’ll just mention that perhaps the most amusing behavior was a sort of sparring with the beak, called a courtship ritual in this short video, but actually used more widely as a family greeting.

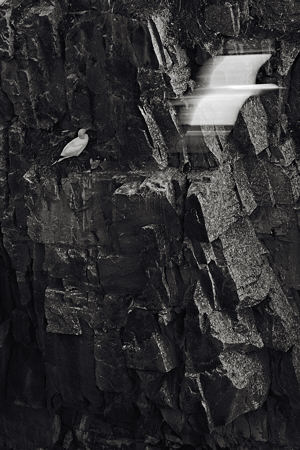

Now I’m not much of a wildlife photographer, though I have been stalking (or stalked by) deer lately. But birds are fascinating for their movement, so I thought I’d try extending the approach of letting motion register by using longer exposures, as I’ve done with water and, more recently, the seaweed. It’s hardly a novel concept, and I’m sure it’s been applied to birds by many others, despite my impression that the vast majority of bird photography is more about stopping motion to get a sharper, more detailed image of the bird itself. No doubt there are other photographs out there similar to mine. Nevertheless, I haven’t seen any yet, so please send links to any you know of.

None of the photographs, I can safely say, are particularly noteworthy, but what I found interesting was the power of a symbol to hijack the project. Can you guess what it was? Warning: spoiler in the next paragraph.

As soon as I examined on the camera display the first image of a gannet in flight, gliding past the cliff, white wings spread and softened by the motion blur, I thought of angels. I began seeing the flying birds as a protective presence, watching over the ones huddled against the (dark) rock. Like the jingle you can’t get out of your head, that was the idea I had in mind as I continued to capture images, aiming deliberately (to the estent possible) for the similarly suggestive. What do you think: does the idea come through In the selection here? Does anything else come to mind?

There’s no good reason not to think of something else. To the extent the angel impression is evoked, reality has likely been distorted. There’s no evidence of any guardian role in gannets. In fact, as naturalist Chris put it, the birds swooping about the rock seem to fly for the love of flying. They embody and represent the freedom to go where they will. That’s equally strong cultural symbology (and more universal), which seems to be at odds with the notion that the colony is in need of protection. If we’re doing symbols, I don’t mind drawing on either version; both seem powerful and, in some sense, appealing. But it may be their conflict is responsible for the images not working well. Or perhaps I’m exaggerating out of all proportion the role of symbolism, and these come across as just plain images of gannets at home. How do they strike you? And has a symbol ever done you in?

Steve:

I’d fly.

You may have seen pigeons handled this way. Their changing configurations, drawn out over the span of the exposure as they progress, says things about them that a sharp image cannot convey. The gannet soars while the pigeon flaps and the drawn out shapes differ to that extent.

The first image presents the difference with the birds tucked away on their cliff as one of their fellows carves a path. The doughty penguin shuffling over the ice versus itself, the rocket in the water: the Canada goose, a pooping goof on land vs. the royalty of our skies – these represent the ascendancy of ascending for these creatures and for our opinions of them.

Cross two fingers at a right angle and by that simple act you evoke a world of meaning. Nail two boards in a like configuration and put the result on the wall and you will start religious conversations. That said for whatever reason that I said it, those gender symbols do me in daily.

These remind me of the chronophotography of Etienne-Jules Marey. There’s a book, “Picturing Time,” from the University of Chicago Press about his work in aviation and other fields that also explores how the images that came from chronophotography had a profound impact on art (in particular, Cubism and Futurism). The book is full of beautiful and somewhat eerie images.

The hand and the spiral, together and separately, are my go-to symbols. I struggle with myself about the hokiness of them, but always fall back on: “an ill-favour’d thing, but mine own.”

Melanie,

Thank you for the introduction to Marey; I’d only known of Muybridge in that area. At the Wikipedia article there’s one of his photographs of a pelican landing. He’s also the guy who studied cats landing on their feet.

The hand and spiral seem like great symbols. Both asymmetrical and highly variable, and they feel significant, though in many possible ways.

Jay,

I’m sure you’re right, I must have seen plenty of pictures of pigeons like that. Also right that still vs. moving was important. I didn’t make any photos of just flying birds.

The Canada geese are just starting to honk by overhead in the last few days here. It’s definitely fall now.

Steve:

Climate would dictate their migration. Many years ago the geese around here chose to winter over and have been doing so. They will form up in v’s for the sake of parading about, but the v rarely points south.

Steve:

That symbols crashing thing went right through my head without so much as slowing down!

Symbol-as-object is a wonderfully loaded topic, as you might expect me to say. The throwing star of David, Zildjians cut into symbolic shapes to be crashed – oh my.

Indeed a loaded topic, but normally not of great interest to me. That’s why I was surprised that such a specific symbol (angel) even became a question with these photos. Unlike Melanie and Jay, I have no personal symbols, either in the sense of ones I’ve worked with or feel close to. Unless you count favorite subjects like trees or rocks; those could be used symbolically, but I don’t think I do. I definitely do have an interest in the sorts of individual and cultural associations they might have. Symbol, though, in my vocabulary, implies a more well-defined meaning.

I wonder also if “angel” was lingering in your mind from your recent reading of Wim Wenders. Not so much a symbol as an echo.

“Symbol, though, in my vocabulary, implies a more well-defined meaning”

–and that would be . . . ?

Melanie,

I had totally forgotten, but you’re quite right. In addition to the reading, I saw Wings of Desire a few months ago.

About symbol meaning: I haven’t really thought about this, and doubtless I’m on shaky ground, but it seems I want to distinguish something a bit like denotation and connotation. In the case of the angel, I was only thinking of the generic sense of protective thing, which could be served (in a different setting) by an overhanging eave, a spreading tree, etc. I didn’t want to bring in conventional associations with Heaven, God, or special powers. And I certainly wasn’t looking for anything so detailed as Rob was recently. I suppose it’s all symbolism, but I believe there’s a real difference.

Joie de vivre!

Buzzing and flying for the love of doing it. One of my heroes is Chuck Jaeger because of his love and competence of flying.

Steve:

Looking at my relationship to symbols I would have to say that it centers on simple diagrams and their often rigid graphic relationship to a given system of belief or affiliation. I have been tempted to play with this rigidity, which I encountered in my youth, by moving graphic symbols around. But notoriety is not one of my objectives.

Birgit:

I bet you like Chuck’s cool.

Steve,

‘Be cool’ will be my mantra this week for solving complicated affairs.

Birgit,

Let’s up your complicated affairs don’t don’t require ejecting over the desert with your flight suit on fire.

A flaming rocket jockey he.

Good news, my friends. I am not planning on ‘buying the farm’!