19th century shtetl

In the book, Journey to a Nineteenth-Century Shtetl, Yekhezkel Kotik shares his memories of living in a shtetl not far from Soutine’s home of Smilovitchi in what is now Lithuania and what was once the part of Tsarist Russia that held on desperately to the edge of its borders with dirty fingernails. Of the superstitious beliefs of the townspeople, and there were many, there is this one in regard to death,

And when the body is lowered into the grave, the Angel Dumah appears beside him and asks, “What’s your name?”

To his misfortune, the unlucky deceased has forgotten his name. The Angel Dumah rips open his belly, plucks out his guts, and flings them into his face. He then turns the corpse over, strikes it with a white-hot iron rod, subjects it to excruciating torture, and finally tears the body to pieces, and so on. Everyone believed those things as though they were irrefutable facts.

As a child, Soutine was obsessed with the rituals of death, going so far as to participate with other children in the shtetl in mock funerals and burial rituals. If this particular superstition was known to Soutine, and it seems likely that it did, one can only imagine what a gruesome story such as this would do to a sensitive child who wrapped himself in white sheets and pretended to be dead on a regular basis.

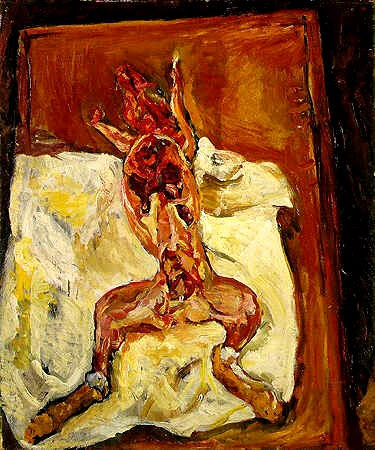

Flayed Rabbit, 1924, Barnes Collection

Although Soutine was from an Orthodox Jewish family, he lived in a part of the world deeply influenced by the teachings of Ba’al Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidism and a Kabbalist whose mystical Judaic teachings stressed the primary idea that God is in everything. And while this has only been speculation by Soutine scholars, one should add to these above mentioned superstitions and teachings whatever psychic weight Soutine carried with him for breaking Judaic law by becoming an artist, something taboo to the Jewish religion at that time. Additionally, putting all speculation aside, there was the very real abuse and neglect Soutine suffered as a child as well as the rejection by his family and his community over his desire to create art.

The Angel Dumah, also called the Angel of Silence, is not an unfamiliar concept in Judaism and has more than one meaning dependent on which school of Judaism it pertains to. For instance, Dumah is the name for a city in Judah and is mentioned in The Septuagint and in Rabbinical Literature; Dumah is the name for the angel who is in charge of souls in the nether world, the one who takes the wicked souls and casts them down into the depths of Hades. But every evening, Dumah leads the souls out of their torment and into Hazarmaveth, (the Courtyard of Death and also a geographic location mentioned in the Old Testament) where they eat and drink in absolute silence.

It is also written in Rabbinical Literature that the soul cannot leave the body entirely until it cries out in confusion from its decaying body and Dumah takes it immediately to Hazarmaveth. So there seems to be a mutual working relationship of give and take between the soul and the Angel Dumah and is inherent in all of Judaism which relies on a give and take between a person and God, whether it is intellectual or mystical or in Soutine’s case, artistic.

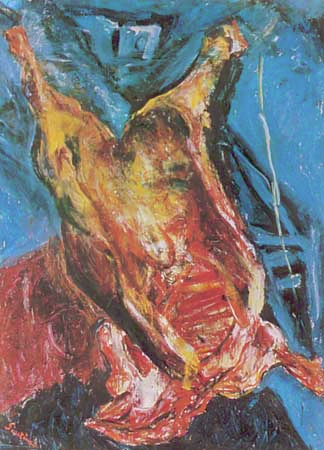

Soutine the adult who rarely spoke of the harsh conditions of his childhood, who because of his early years of poverty and lifelong stomach ulcers viewed food as a luxury and never ate anything beyond basics like potatoes and milk, re-enacted both his childhood death rituals and food rituals in these carcass paintings, exorcising whatever fears and fascinations he held towards his religion, culture and memories. Jews were forbidden to be artists because to be an artist is to create and only God can create. Also, according to dietary laws, an animal was to be killed quickly and as painlessly as possible, with the blood carefully drained from the body. It is not to be gutted and posed nor is it to hang in a studio with regular drenchings of fresh blood, as Soutine famously did when he created his Side of Beef painting, based on the work of Rembrandt. Yet Soutine immersed himself in the act of painting, of creation, with an abandon that can be likened to religious zeal.

Side of Beef, 1925

Soutine

Tree Smith:

Thanks for adding that. I was going to say something about the forks being in some manner analogous to artists’ tools and the studio being somewhat the abbatoir where conceptions and perceptions are eviscerated, but I won’t.

Also, could you expand on the subject of creativity? I was under the impression that the Jewish prohibitions extended only to graven images and singing a new song onto the Lord was encouraged.

Hi Jay, I don’t completely understand the prohibition against art that existed in Soutine’s village. I touch on this in Part 3, but Soutine was nearly beaten to death when he painted the portrait of the village rabbi. The money he got from the court settlement got him out of the shtetl and into art school.

There are many examples of Jewish art throughout history, art historians and Judaic scholars seem to emphasis the Medieval period, but as you pointed out, there were not “graven images” for fear of idolatry. I thought this was interesting… http://www.commentarymagazine.com/viewarticle.cfm/jewish-art-14739

But I’m really not quite sure what you want me to expand upon. It seems the Jews have a long history of creative expression even without figurative painting and I’m afraid I’ll either state the obvious or miss the mark entirely!

Tree:

Sounds like things were unsettled in the shtetl. The rabbi sat? What was he thinking? Sounds like Soutine took a fall while the reb walked.

Not meaning to prod. I have to think that artistic creativity had a specific definition in the shtetl context that may have extended beyond some form of prohibited imagery. Artists are such troublemakers after all.

I’ve always wondered about that, too. Why did the rabbi sit for a portrait? Or, did Soutine draw from memory and then show it to people? Don’t think I’ve ever seen a full explanation of it but it definitely sounds like a set up.

Quite a few stories of Soutine’s secretive art making and his punishments on being caught. I’m sure as poor as his family was, art was seen as a frivolous waste of time.

I’m not an expert on the shtetl where Soutine grew up or its dynamics but it sounded like a dreary, unhappy place. Maybe creative juices were released during services (?) There had to have been musicians, at least.

Maybe one of the reasons people believed in such outrageous superstitions like the one I write about is because that was their creative outlet.

In the movie Local Color, a painter rages against the idea that growing up in a ghetto is supposed to predispose an artist not to see and paint beauty.

Chagall, born in a Jewish ghetto, painted fish motifs out ‘of respect for his father’ who did ‘hellish work, the work of a galley-slave’ to support his family.

Tree:

In loose connection with this are two novels by Chaim Potok: “My Name is Asher Lev” and “The Gift of Asher Lev”. These depict the fraught relationship that exists between an artist and his Hasidic community.

Birgit, there is such a joy to Chagall’s works. How different from Soutine!

I’ll see if Netflix has that movie.

Jay, you’re the second person to recommend the Potok books to me so I take that as a hint from the universe to read them asap!

An enjoyable article, Tree. I know almost nothing about art or Soutine, so not only the fine meanings but the large meanings are unfortunately lost on me of these pieces, but I would offer a comment about Hasidism, though I am not one myself. At the one Hasid service I attended, I marveled at the seeming rapture the Rabbi neared as the singing of the prayers reached culmination. It was my understanding that this was the radical change( joy and expression, as opposed to immersion in texts) that Baal Shem Tov brought to Jewish prayer. At the same time, there are numerous references to how strictly observant lifestyles were required to be. In my mind I am not rambling, but I apologize because to everyone else I might be, but I remember the reaction to Mapplethorpe when that exhibit came to Cincinnati, and whether that was truly “art”. There are numerous paintings and statues of Jewish religious figures dating to antiquity, so I would be surprised that it was the act of painting a rabbi that was a problem. Perhaps how Soutine chose to portray what he portrayed was, umm, ahead of his time.

Hi Q, glad you like the article. I appreciate what you wrote about attending a Hasid service–sounds interesting!

Yes, one may find examples of Judaic art throughout history. However, Judaism is not just one way and my understanding is a prohibition against certain forms of art predominated for centuries.

When one compares how synogogues have been built and decorated historically to cathedrals, one sees the drastic difference. A comparison like this is very common in the academic world of art history.

Of course, plenty of Christian sects had or have the same decorating prohibitions, but maybe for different reasons.

More specifically, according to my research, friends of Soutine and Soutine himself, he most definitely was punished more than once for doing what was considered taboo.

Tree:

For many, the creation of art is seen as prideful, and therefore one of the seven deadly sins. However, a creative spirit would raise a tentative head in the preparation of fancy foodstuffs like chow-chow and the practice of fractur. among the Mennonite faiths. And let’s not forget distelfinks.

There is a fictionalized short story about Soutine. It is Roald Dahl’s story “Skin.” Just to warn you, it is no Charlie and the Chocolate Factory–the story’s gruesome and definitely not for young children! I read the short story for university. I didn’t know Soutine was a real figure until I read this post. Thanks!

Dear Tree Smith,

I find your essay on Soutine very helpful and informative. But I am having difficulty in tracking down the quote that you cite about Dumah the Angel of Death in Kotik’s book : Journey to a 19th Century Shtetel. Could you tell me on what page the quote is cited?

Thanks so much,

Eric Kandel

Dear Tree Smith,

I find your essay on Soutine very helpful and informative. But I am having difficulty in tracking down the quote that you cite about Dumah the Angel of Death in Kotik’s book : Journey to a 19th Century Shtetel. Could you tell me on what page the quote is cited?

Thanks so much,

Eric Kandel

Thanks so much, Eric.

I’m afraid that, while I remember reading that in the book, it’s been too long for me to remember the exact page. A lot has happened since I wrote this and I am unable at this time to find my notes and research.

I’m glad you read the book on Shtetl life. I found it very interesting and worthwhile.

Sorry I can’t be of more help but I know it’s in there.

Google comes to the rescue here. Tree’s quote is exact, and appears on p. 157, at least in the edition of the book that Google references. There are footnotes there that may be of interest to Dr. Kandel or others.

Here’s the URL I found by googling the phrase “misfortune, the unlucky deceased has forgotten his name. The Angel Dumah rips open his belly”:

http://books.google.com/books?id=mMT9BuKi8pYC&pg=PA157&lpg=PA157&dq=misfortune,+the+unlucky+deceased+has+forgotten+his+name.+The+Angel+Dumah+rips+open+his+belly&source=bl&ots=UIljR6R-Bp&sig=2h9W5M3I7zYrLt0Uf0TtJrbDO_c&hl=en&sa=X&ei=Nja4UpOYL8amygGD3IGgBw&ved=0CCsQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=misfortune%2C%20the%20unlucky%20deceased%20has%20forgotten%20his%20name.%20The%20Angel%20Dumah%20rips%20open%20his%20belly&f=false

I’m so delighted that this nearly dormant blog is still serving a useful purpose. Tree, how’s everything?

Thanks so much, Stephen!

I’m doing OK, thanks. Very busy working and caring for our nearly three year old daughter. I’m afraid there’s no time for writing these days.

How are you? Still doing photography, I hope.

Well, sort of, though you wouldn’t know it from how long it’s been since I updated my web site. I’m working intermittently on a project that is a follow-on, with the same print artist, to In Praise of Trees, described on this very blog. But I’ve been mostly occupied by other web projects and recent ventures into “deep learning” (google!), which coincidentally, ventures into Kandel territory. Same job (software), which had the unexpected benefit of taking me to India the last couple weeks.

Dear Steve Durbin,

Right you are; it is indeed on page 157 in the edition I have. The Index was Completely uninformative and misled me. Thank you so much for leading me to right quote.

The more I get in to Soutine the more I like him. I always enjoyed him but the Soutine– Beacon exhibition in NY 2 or so years ago blew me away.

Anyway I am much in your debt Steve and Tree for this very penetrating discussion

Eric.

Eric, have you seen the Soutines at the Barnes Foundation? They are well worth the visit.

Stephen, a trip to India sounds like quite an adventure! Sounds like that active mind of yours remains active. Happy Holidays!

Eric: Enjoyed your book on Vienna.