Lawrence Weschler has a delightful article in the Virginia Quarterly Review on the work of the young twins Trevor and Ryan Oakes. They are very original and persistent thinkers about how we see and the consequences for art. For example, though we’re seldom aware of it, our nose intrudes in almost half the visual field for each eye. This may be subliminally responsible for the claimed common appearance of roughly triangular shapes in the lower parts of pictures. (I haven’t attempted to confirm this, but it’s something I’ll be looking for in future, especially in abstract art; ask me again in six months.)

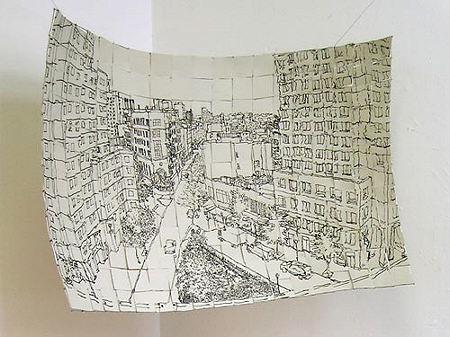

Most of the article is about a novel approach to rendering perspective, something that June particularly has discussed on A&P. Her prime example of Rackstraw Downes is another artist especially concerned with the wide peripheral vision, like the Oakes twins. The technique is essentially spherical projection combined with independent focusing of the artist’s two eyes, one on the scene being depicted and one on the paper being drawn on. The brain’s binocular vision, attempting to deal with this abnormal input, essentially overlaps the two views, so that the artist can “simply” trace with a pencil the scene that appears to be on the paper. I’ve tried this enough to see how it works, though it would clearly require practice and patience to keep it up. And it can only be achieved for a smallish angular range. So the brothers constructed a frame (see the article) which allows them to build up a panoramic image by building it up bit by bit.

This technique is unrelated to any hypothesized by David Hockney in his studies leading to the book Secret Knowledge, in which he presents evidence for the use of camera obscura, camera lucida, lens, or mirror by many artists going back to the Renaussance. Despite the popular interest, his conclusions remain controversial (see James Elkins for a skeptical review from a conference). For his part, Hockney seems to be concerned with cognitive or psychological, rather than optical perspective, as I mentioned in a previous post on landscape.

I haven’t been much worried about perspective in my photography, but I’m starting to think more about things that govern the viewer’s sense of spatial relationship with an image. For example, why does it feel that one is looking up to these branches (from Meeting Sky)

whereas those in the following seem to be viewed with a more horizontal gaze?

Have you had to deal with perspective in your own work? Is it something you’re aware of when looking at pictures?

Talk about serendipity! This morning Tyler Green posted on Carel Fabritius’ tiny, mysterious painting and its odd perspective. According to the web site for the painting at the National Gallery (italics mine):

It may be that Hockney’s techno tricks were not the only ones used early on.

Steve:

I see what you mean with your illustration. The second photo does create its own set of expectations. What’s needed to complete the effect would be for Birgit’s duck to wander over from her post.

But I would note that experience can influence expectations even here. Last summer I reclined under a somewhat similar set of twigs and branches, and watched swallows swallow mayflies. I am now imprinted with that and needs mentally rotate myself to an upright position before empathy can kick in.

And, boy, I am having a hard time with Hockney. At least twenty five years ago a Dutch team installed an exhibition at the CMA that pretty much covered the same ground.

Jay,

Does “having a hard time” with Hockney mean you’re not convinced of his thesis? Or is this a statement about his paintings? For myself, I find both interesting, but not overwhelming.

Steve:

Interesting but not overwhelming indeed. I feel that Hockney has led a charmed life. He has a public reputation that far exceeds what I feel are his accomplishments. But caution is due here as my opinion may be based upon a misreading of his work, or an insufficient eye on my part.

Without reading his book, I needs exercise caution as well with the ” aided by science” thesis that he advances. The assumption that many artists from the Renaissance on used optical devices was something of a given – or so I thought. It was as though he had come out with the breathless news that the use of linseed oil as a binder and hardener had influenced the art of painting. But then I have’nt read his book.

As a perspective junky, I enjoyed the first picture.

I am with Jay in saying that ‘But I would note that experience can influence expectations even here.’ Having unsuccessfully tried to photograph tall birches with their spectacular fall colors last year, I am wary about the second photograph. For me, the branches do not point down but the slant reflect the manner in which the branches were photographed.

And, ‘Birgit’s Duck’ has begun to walk onto a 12 x 10 board, trying to teach her to paint moving water.

Birgit:

In the spirit of Angela’s experiments with earth as a medium, your duck could use wattle.

Jay,

The penny has not dropped, perhaps because my brain is mush after a marathon-like day. I had to look up ‘wattle’ on wikipedia. Maybe, I figure it out walking home in a little while.

Jay,

Hockney believes that optical devices were used both earlier and more extensively than anyone previously thought. His argument was initially from considerations of artistic style and technique–i.e. how the pictures looked to him–but he later had some help on the science from an unimpeachable physicist. Still, there are interpretive issues in applying the scientific understanding to specific paintings and drawing conclusions.

Personally, I value Hockney more for originality and interesting idea, rather than as a great artist.

Regarding the duck, what’ll she do for the image?

Steve,

I’m not feeling well at the moment, but I was in good enough shape to read (or read at) the Wechsler article you linked to.

I am going to either buy that Virginia Quarterly Review number or, barring that, print out the piece — it’s both fascinating and illuminates for me something about my wacky urban-scapes.

I am also slowly reading a book by William L. Fox, called “Aereality”, which articulates a kind of perspective I used in one of my big desert paintings. Fox was recommended to me by Mary Hill (one of my Nevada clients) who said she found some of his earlier ideas evinced in the telephone poles I use in many paintings. I am waiting for Amazon to send me the book she spoke of, “The Void, the Grid, and the Sign.”

Slowly I feel like I’m gathering information about why I seem to see (or perhaps, more specifically, paint) things the way I do.

I love it when someone else says what I meantersay, only better. Many thanks for the link!

I shall try to check in about your photos soon, when, if the crick don’t rise, my brain starts to function more normally.

Birgit:

Please don’t wrack your brain – my comment was a poor punnish play on “waddle”.

June:

Hope you’re feeling better.