In the beginning, all music was live.

But since 1877, thanks to Thomas Edison, we’ve had sound recording. By the turn of the century, musicians could play in front of a microphone or two, and their performance would be captured, preserved and reproduced. People anywhere could listen to a singer or a band any time they wanted, by playing a record on their phonograph. Sound recording wasn’t considered an art form. The sole purpose of recording was to faithfully capture a live performance. Though the technology improved greatly over the first half of the 20th century, the role of recording remained the same.

In 1947 jazz guitarist Les Paul released a recording of himself playing 8 different guitar parts. This was the first known “multi-track” recording, and was made by recording onto wax discs. In the 50s, Buddy Holly would record a rhythm guitar track on one tape recorder, then play it back and play a lead guitar part along with it (or sing harmony w/ himself), recording both onto a second tape machine.

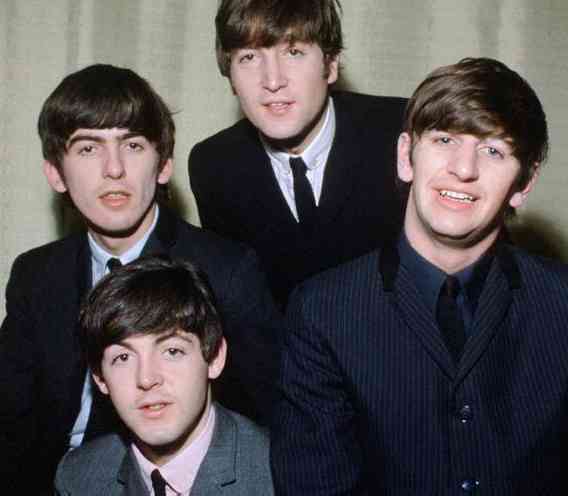

When the Beatles recorded their first albums in the early 60s, they were basically traditional recordings, in the sense that they would rehearse their parts and then perform them together live in the studio. Over then next few years they began using the new 4-track tape machines, that allowed them to add other tracks later, played either by themselves or other musicians. And they could adjust the mix (the relative volumes of instruments) after they were recorded. So they had more control over the recording process, but the goal was still to record something that sounded like a live performance, even if it wasn’t.

By the time they recorded Sgt. Pepper in 1967, and Abbey Road in 1969, everything had changed. The Beatles, along with their producer George Martin, were using the studio not just to capture their performances, but as a creative tool in itself. They recorded tracks backwards, or at faster and slower speeds. They cut up the tapes they had recorded and pieced them back together out of sequence. They layered tracks, both musical and otherwise, creating dense soundscapes that would be difficult, if not impossible to recreate in a live performance.

Were they cheating?

I ask this in the context of other discussions that have taken place here on A&P, about painters looking at photographs, or projecting photographs, or printing photographs on canvas. I ask it in the context of comments I’ve read elsewhere by photographers. About whether a photo composed in the camera is more legitimate than one that’s been cropped, or whether one that’s printed in a darkroom is more legitimate than one printed digitally, or whether the more an image is manipulated in Photoshop the less “true” it is.

I should mention that things in the music world, as I’m sure you know, have come a long way since the Beatles’ explorations. The number of tracks on tape recorders went up from 4 to 8, to 24 then 48, and at this point, with digital recording, are practically infinite. Drum tracks can be generated entirely in the computer, as can many other musical parts. Sounds can be sampled from the real world, or from other records, then used within a new recording. You can buy prerecorded loops of sounds (drum beats, bass parts, etc.) and use them in your projects. You can record the tracks for a song, then go back and correct out-of-pitch vocals, speed up or slow down tempos of individual tracks, and cut and paste sections from one part of the song to another, squashing and stretching them to fit. The same kinds of issues we discuss for visual art are also debated among musicians and music fans.

So where do you draw the line? When is it real art, and when is it cheating?

D.

It is so wonderfully complicated that I prefer to think of it simply as a question?

Here was a recent show that examined the question directly:

http://www.independentschoolofart.org/

Then to: Events.

Then to: Past Events.

Then to: Black Market Auction.

Interesting question David. In my personal opinion I don’t think any of it is cheating because I don’t think there are any rules. If there are no rules in art or recording then you can’t cheat.

It makes me wonder as to where all these so called rules came from. Who says you can’t use black watercolour paint, you mustn’t use photographs and who says recordings must sound live? I reckon if Da Vinci was alive today he’d be using photoshop, breaking all the so called rules and discovering new things by doing so.

Of course he isn’t so we’ll never know!

John,

You raise an interesting point. Can we look at art history and study what were the “rules” of the past, who “cheated,” and whether they got away with it? That might inform the current discussion.

This is an issue that has interested me since (well, during, actually) graduate school.

The idea that they “cheated” is, to me, bizarre. It would be like asking whether a person who gained literacy and then wrote down their story rather than committing it to memory was cheating.

Before the availability of audio recording (and related sound manipulation processes) virtually all music performance was created in the same space and time occupied by the observers, either by improvisation or by more or less faithful realization of a score. In this sense, music has been more like theatre, dance, and other time-based art forms that are traditionally performed live.

On the other hand, art that is created in final objective form has also existed for a long time: painting, sculpture, literature, and more recently photograpy and film.

Using a recording process to create sound art seems no different. It simply allows musical artists to create both kinds of art – the kind that is temporily bound and different each time it is “realized” anew, and the kind that is created in a more or less fixed form by the artist.

If using a recording process to create music is “cheating,” then making a movie, a photograph, or a painting would also be “cheating.”

Dan

David,

It is cheating if you claim it to be something that it is not (this is a ‘live recording….’; that smoke was really over Beirut; ‘hand made’ etc).

But if you just say ‘I’ve finished, what do you think of it?’ then how could you possibly be cheating?

Yeah, I think David is spot on. You’re cheating if you’re saying it was done one way but it was actually done another.

Wait a minute. That’s not cheating, that’s lying isn’t it?

Maybe our worry about cheating is a result of school exams. When we leave school we feel everything is an exam, but it isn’t I don’t think. Things can be lying, immoral or illegal, but unless it’s a game with rules, it can’t be cheating. Can it? This is all a bit mind numbing!

Wow.

So, suppose I write a very complicated piece of music. It’s so complicated that it can’t be performed with two hands at a piano; so I get six friends to all sit down and perform the piece. We record the performance. Is this cheating?

Suppose I take the same piece, but instead of using a set of friends, I laboriously cut holes in a roll of paper, load the paper roll into a player piano, and start the piano, then record the performance. Cheating?

I take the original sheet music, scan it, and run it through software that produces a midi stream. The midi stream runs through the cable to my little black box, which contains samples of piano (such boxes exist). The digital output of the box is burned directly to a CD, which is then distributed. Note that at no time was the music ever realized as sound until the consumer popped the CD into their stereo. Cheating?

There aren’t any rules, it seems. With no rules, you can’t cheat.

I think it’s clear that there is no cheating unless there is misrepresentation. There’s no philosophical or moral question so far. But a problem arises when listeners/viewers make assumptions, informed or not, based on historical practice or not, and then accuse artists of cheating if they learn the truth of the matter. For artists using non-traditional techniques (or just unusual ones that the public may not be familiar with) and trying to make a living, this could be a serious problem. The question is, how do you present your work? How much do you say up front? Is it worth arguing with those who accuse you of cheating?

This is an interesting discussion.

The reason I used the word “cheating” is that I’ve heard it stated that way in regard to painting, that some people think it’s cheating to paint from photographs. Or that if one does use them, it’s just as an expedient substitute for (the preferred mode of) painting from life. This has been much discussed here on A&P.

And I’ve read statements by photographers who feel that the less you do to an image using Photoshop the better. The software is dismissed as a necessary evil that should be used sparingly, if at all. Both of these opinions reflect a sort of purist attitude toward the mediums involved (painting and photography). I’ve come across similar types of attitudes toward music, especially when you get into issues about computer-generated drum tracks, or sampling.

My personal feeling is that photography (for painters) and computers (for everyone) are not just technical aids to achieve the same results you could achieve without them (just quicker or more easily), but are in fact incredible creative tools that open up new possibilities. Most photographers, from what I gather, view Photoshop as simply a digital darkroom, and many seem to feel that it’s overly complex and contains many unneeded features. Maybe because I’m a painter, I’ve never looked at Photoshop as a darkroom, but as an image manipulation tool (and a fantastic one). I use some of the same features that photographers use, but I use them in ways that many photographers would find appalling. And in music, I personally find the possibilities opened up by MIDI, sampling and ProTools to be incredibly exciting, but I’ve met people who think it’s not real music if it comes from a computer.

I asked if the Beatles cheated, knowing that, of course, nobody would think they did. But it seemed like a good way to initiate a conversation about what our (perhaps unspoken) rules are. Even though most of us agree that there are no rules, we still have prejudices about what constitutes real painting, real photography or real music.

This is sort of funny. The question as I see it is “are you personally moved by what you are hearing, reading, seeing etc.” If not it “ain’t” art to you. Art can’t be a science, if it were, then all of our work would look and sound the same. Oh forgot there is a movement to do just that. Sorry.

So some musicians make collages… or mixed media work with some original portions and some collage portions… As long as proper permissions and attributions are used, it doesn’t sound like cheating to me.

I’ve thought about this off and on for a few years, and here’s what I think:

There are art forms (like painting, drawing, sculpture, etc) that are “obviously” not mechanical captures of reality. Nobody expects a painting to be photo-perfect. If one is, the photorealism is assumed to be a deliberate choice on the part of the artist, and possibly that it was technically difficult to pull off.

On the other hand, there are art forms (like photography and, maybe, recorded music) that are “obviously” mechanical captures of reality. Here, the default is to believe that reality at the time of the capture is faithfully represented by the recording.

To focus on photography, if it’s indeed your expectation when looking at a photograph that the scene represented looked “just like” the photograph at the moment the photo was taken, then if you learn that the photo was heavily manipulated, you are liable to think that the photographer “cheated”. The same is true with a sound recording if your initial belief is that it faithfully represents a performance that could have been experienced live.

Indignation stems from violated assumptions. If the artist makes clear that an audio recording is not simply a “straight” capture of a live performance, there is no misrepresentation and nobody should feel deceived. Likewise if it is made clear that a photograph is “manipulated”.

The thing that still perplexes me is specifically about photography. It seems that a great many people believe that a photograph is less good if it has been “manipulated” than if it hasn’t. As far as I can tell, this is no longer an issue of broken assumptions or misrepresentations, but rather one of simply attaching more value to “straight” photographs. I’m still not sure where this value judgment comes from.

Possibly it comes from the same place: that photographs are “obviously” faithful reproductions of reality, or ought to be, and so manipulated ones are somehow vaguely disreputable, even if specifically identified as such?

The thing that still perplexes me is specifically about photography. It seems that a great many people believe that a photograph is less good if it has been “manipulated” than if it hasn’t. As far as I can tell, this is no longer an issue of broken assumptions or misrepresentations, but rather one of simply attaching more value to “straight” photographs.

Maiken, thank you for picking up on this issue, which is really at the heart of what I’d hoped to explore with my post.

It’s probably pretty obvious to everyone that I wasn’t in any way suggesting that the Beatles really “cheated”, or even that there are any rules to break. The Beatles are 5 of my all-time favorite artists in any medium. I was playing devil’s advocate with my question, hoping to make a analogy to the attitudes about photography you describe (as well as those about painting). For me it’s not a matter of misrepresentation (that’s a separate issue), but of a value hierarchy that some people place on different ways of working. Like you, I’m perplexed by it.

maiken,

It seems that a great many people believe that a photograph is less good if it has been “manipulated” than if it hasn’t. As far as I can tell, this is no longer an issue of broken assumptions or misrepresentations, but rather one of simply attaching more value to “straight” photographs. I’m still not sure where this value judgment comes from.

Leave aside for a moment those with very conservative outlooks (and there are plenty of people who remain appalled that PS exists, let alone about what people do with it), you may find a part of the answer to your question in this article.

I can look at an obviously constructed additive photo-type artwork and be plain uninterested in it because I am more interested is what is seen than what is imagined.

That doesn’t make the manipulated or additive PS artwork any less good than a ‘straight’ photo, but it does make it an expression of a different skill.

I’m on record as saying that there is no such thing as an unmanipulated photo, so there is no black and white here. I also think that the ‘reproduction of reality’ is a bit of a dead end in terms of enquiry. You very quickly get to the question of ‘what is real’.

David,

Comments crossing in the post again….

For some people, to be sure, the craft that they know is the craft that they value. And a lot of the ‘I hate PS’ comments come from that source.

I don’t hate PS, but I do think it is bad at doing what I want software to do (and I’m not alone in thinking that).

I can’t remember what percentage I’ve used in the past, but the overwhelming part of the art process that interests me has happened at the moment that I press the shutter. And art is a verb….

That doesn’t stop me appreciating other art forms. I’m quite fond, for example, of this ‘photo’ by JohnJo but I wouldn’t have produced it. As a viewer, I care not how something is produced, but as a producer I care a lot.

Helpful?

It seems that one person or another has already made every point I would make, but reading the post and the comments was fun. I gather that what bothers people is misrepresentation. So long as the artist doesn’t do that, no one seems to be terribly concerned about the methods.

But in many arts, I have noticed the purist attitudes of those who would disagree too.

Mmm… I just thought of something. From photography. Having to manipulate print after print in the darkroom is a royal pain in the ass if you’re trying to do any kind of quantity. Getting a good neg (that is — the one that does what you want) in the first place is a solid, practical way to easily produce consistent prints in quantity, so there’s a case where “purism” is sensibly grounded.

In painting, getting a line or brush stroke right in the first place gives a work a special zing that overly worked or fussed with stuff doesn’t.

One time, while playing bass in a band, the keyboardist gave me a piece of advice, “Play each note like you mean it.” I finally started doing my job in the band then.

But you really don’t get those fresh effects when you fuss with stuff too much. If there weren’t any rules, then that wouldn’t be significant. But that is a rule that gets results. Therefore saying there’s no rules is a particularly harsh rule.

Leave aside for a moment those with very conservative outlooks (and there are plenty of people who remain appalled that PS exists, let alone about what people do with it)

Well, let’s not leave them aside! The view you go on to express, that “straight” photography and “manipulated” photography are just two different skills, seems perfectly reasonable to me. I can also understand how one may be more interested in one than the other.

But I find a different view surprisingly widespread, one that seems very much like what you write off as “very conservative”. It seems to me that lots of people, if they admire a photograph, will be disappointed if they learn that that image was “manipulated”, and then think less of the image.

I’ve had discussions with many such people, in which I explain that my personal goal is to represent what I saw, subjectively rather than some poorly-defined “objective” representation of the scene. I sometimes also explain that it’s a fallacy to imagine a “completely unmanipulated” photograph. Somehow, this often makes it more OK to them that I “manipulated” the image.

Clearly, these folks have an internal value hierarchy that places “straight” photography at the top, and “additive”, or “completely fabricated” photography at the bottom, and furthermore, assigns moral value to different motivations the artist may have had for manipulating the image. This is all still something of a mystery to me.

Any thoughts?

Therefore saying there’s no rules is a particularly harsh rule.

Ha, Rex you’ve got a good point :)

How about, “there are lots of rules, but no absolute ones. Your rules may be different from my rules. And the rules can cahnge at any time.”

Also there’s a big difference between overworking something (which can happen in any medium) and using tools creatively. I guess because I’m not a photographer, I hardly ever use P’shop as a darkroom (except when I’m documenting my work). And my end product is never a photograph, though photographs may be what I use to get there.

Comments crossing in the post again….

Colin, the difference in our time zones seems to have neutralized the differences in our blogging habits :)

The distinction you make between being a producer and a viewer makes lots of sense. And you seem to have a better understanding of those differences than some people. Though it doesn’t account for the value hierarchy that Maiken mentions, and that I’ve encountered also.

I wonder if people bring those same value judgements to movies. One of the things I did at my day job was to help create the 3-headed dog in the first Harry Potter film. I don’t think the film was that well-directed, but the effects I thought were pretty convincing. Hopefully people wouldn’t be disappointed if they knew it wasn’t a real dog :)

Maiken, you’re making some interesting observations. I tried to click on your name and go to your website, but there must be a typo in the link. I keep getting errors.

Hmm. For some reason, my website URL got mangled. The correct one is http://www.chromalark.com, a photoblog. I’ve tried to fix the link for this comment.

David, if you’re exceptionally bored, perhaps you could correct the link in my previous comments? :)

Mark, great images! I particularly like Snowtracks and Montreal Overpasses, but many others too. Welcome to A&P.

I’m not bored enough to go back and fix the old links (also, I’m at my day job now), but hopefully people will click through the new ones and see your work.

maiken,

I was only putting the group to one side for the sake of clarity and following a thread in an argument.

The attitudes that you comment upon are very widespread, but they are essentially not attitudes that relate to an art experience. They are about something else.

I’ve written a bit about them here – although I will admit that you have to go looking for it deep in the article.

It is all about working within a convention. We human beings like conventions (habits, stereotypes). They help organise our lives and make things easy to manage. There are a lot of people for whom the convention is the big thing.

So, there are two reinforcing things at play. One is that it is the convention that photos are realistic (they can be counted on as representations of reality and we would recognise the reality if we saw it after the photo). The second is a fear of the use of the imagination. Straight, conventional people like straight conventional photos.

It is the same sort of reaction that people give to seeing a Picasso or a Dali. They ‘don’t understand it’ because it is neither straight, nor conventional. Although over time conventionality changes, such that those two painters are now either in, or nearly in, the conventional set.

As to attitudes changing once you have given your explanation – I think that that may be nothing more than the smoothing given by the words. It sounds plausible doesn’t it? “What you saw”. You are not making stuff up (deals with the use of imagination) which gets you halfway there, and you give a line between ‘reality’ and picture. They may have seen something different, but maybe it is just what was there really and you saw it.

I haven’t yet looked at your pictures – off right now – but I like your words :-)

I think Rex has found the key insight here. Rules, constraints, paradoxically give freedom. The “good negative” example is the perfect illustration. I like it because it reminds me of something we were discussing earlier. Looking back, this brings fond memories of when I was first getting to know David.

Karl, this may seem like I’m contradicting what I said before, but I agree with you. Rules and constraints are extremely useful. I have a pretty strict set of them for my linoleums (I made them up, of course), and they’ve been serving me well.

What I should have said, and Rex called me on this one, is that there are no universal rules. (I’m not talking about laws of nature, like gravity or light refraction, but rules about what one should or shouldn’t do). Any rules that exist are either ones you make up, ones you accept from other people, or ones that are the result of a consensus that you participate in.

I don’t think there’s anything wrong with having and following rules, but I think it’s a mistake to just accept them blindly, or to assume that there’s any objective reason for anyone to accept the same ones you do. Rules of thumb can also be useful, as long as you recognize them for what they are.

David,

I think completely irrational rules can be of great help in art. It is not the rightness or wrongness of the rule that matters (in this unique situation) but the fact of the rule itself. Rules provide a structure, something to struggle with, or against. If the rules are external, it is easier to take them seriously. Making your own rules has the problem that you can change them whenever you want to. Here is where the “painting a day” people have something going for them. They commit to a common rule. If they want to be considered part of that movement, they have to at least make a show of following the rule. And whatever you think of that movement, it certainly seems to inspire productivity.

At the risk of annoying Rex, I could very meekly point out that certain types of neurosis can constrain a person to follow “rules” in a sense, to follow behavior patterns without external rules. In this context, these could be useful to the artist, at least following the argument above. Please Rex, don’t hurt me for saying this. It’s just an intellectual exercise, not a promotion of crazy behavior.

Karl, productivity is fine, but if all it means is painting 365 mediocre paintings a year I don’t see that as a particularly good thing. I realize any judgement of quality is completely subjective, of course. But please point me to an objective measure. (BTW, I’m not saying that the PAD painters are mediocre, just that the quantity in itself is meaningless).

I also don’t agree that external rules are easier to take seriously. If they are backed up by force (like state laws) you have to take the consequences seriously, but that doesn’t make the rules themselves any more valid. External rules can change too, often quite arbitrarily. I think the most interesting artists are the ones that come up with the most creative rules for themselves.

Probably the best rules are the ones that make the most sense to us, or that we find the most useful. Whether these come from us or are external doesn’t seem to make a whole lot of difference. None of them are universal. If you personally find that external irrational rules are of great help in art, you could probably arrange with a friend to make some up for you. Just make sure there’s a good punishment for breaking them :)

PS – Welcome back. How did you like California?

Karl,

I’m with you totally on the constraints stuff. Limits, whether internal or external (rational or irrational) serve to direct focus. Too much freedom can diffuse creative energies. Freedom is seductive, but like other seductions, it can render one dissolute.

As to whether you could be hurt for your hypothesis, well, I suspect I could no more embarrass the wind by shaking my fist at it than hurt you on that point. You express what is perhaps one of the kernels of truth in what became a whole set of non sequitur derivations; furthermore, you keep your assumptions examined.

But imperatives from whatever the actual source of irrationality is have a deadly aspect to them to the exact degree they cannot be examined or changed. In the short run, they may lead to exciting work, but in the long run how exciting is it to be a puppet of the ‘unconscious’ mind?

David,

I see you’re re-examining your phrasing. Karl has a point, but I do agree with you. It’s blind obedience that we must watch for.

A note on quantity. I think you know perfectly well that sometimes quality is achieved through sheer quantity. Didn’t you ever ride a skateboard? Remember all the practice? And then one day, that trick you’ve been trying and trying just comes like you were born to it?

I regard the PAD thing as not a movement. It’s an exercise which is growing in popularity because people are discovering things in themselves that they would not have learned otherwise.

Karl, productivity is fine, but if all it means is painting 365 mediocre paintings a year I don’t see that as a particularly good thing.

If that were the only thing you end up with at the end of a year of the PAD thing, I’d agree.

But that’s not the only thing that’s left at the end, is it?

I mean, you’d have to be a REALLY slow learner to do 365 paintings and not learn something from it.

And, I’d be quick to point out, you’ll learn more from 365 mediocre paintings in a year than you will from, say, five mediocre paintings in a year. And without consistent, disciplined practice, if you only do 5 paintings a year, that’s what you’ll end up – 5 mediocre paintings.

Rex: A note on quantity. I think you know perfectly well that sometimes quality is achieved through sheer quantity.

Paul: I mean, you’d have to be a REALLY slow learner to do 365 paintings and not learn something from it.

Guys, I agree with you. I’m a big fan of both quantity and practice. They’re both very important. My only issue w/ the PAD thing is that it’s just a work habit, but it’s claiming to be an art movement.

Would you consider Practice The Piano Four Hours A Day to be a new musical style?

Well, you must have been reading fast, David, or you would have seen that I don’t regard the PAD exercise as a movement either.

People can say it’s a movement, but that doesn’t make it true. These things are decided in the marketplace, not advertising copy.

I’m a fast reader :)

Actually, I did catch that, and it was one of the things I agreed with. Sorry if I didn’t make that clear it in my answer (I was kind of sleepy). My response to you and Paul was just a quick way to encapsulate what I think about PAD. I have no problem w/ what they’re doing, but there’s just not much about it that catches my interest.

In the context of “rules”, their rule about how they work isn’t a conceptual restraint, but just a way to make them practice every day. If that works for them, that’s great. But as a viewer I don’t see anything particularly new or unique there.

PS – For a good example of what I consider a great rule, take a look at Karl’s post about Jennifer Hoes.

For one series she created porcelain objects cast from her body. That was the rule, that all the objects in the series would be created that way.

As a result, not only did she have a conceptual framework to limit her choices, but she arrived at shapes for her ceramic vessels that wouldn’t have occurred otherwise. And as a viewer, when I look at the work I may sense that there’s something unique about the shapes, even if I’m not sure what that is. When I find out the concept behind it, it adds to my appreciation of the work, and helps me see the connection with other things she’s done.

So that’s what I mean about the artist defining her own set of rules or constraints. Defining the rule itself is a creative act, and it determines the type of work that she will do.

Colin,

I wonder if you’re not being a little hard on those who disapprove of “manipulated” photography? Upthread, you say that you believe this disapproval comes from clinging to convention, and a “fear of the use of the imagination”.

I was once talking to someone who had expressed disappointment that my photos were “manipulated” and I tried to gently learn exactly what they were thinking. One of the things I found interesting was that they said something like “Well, it would have been nice to think that a scene like this really did happen in the world. It’s not something you see every day.”

Perhaps this is an alternate explanation: that people view photography as reporting what the world looks like, and so a beautiful photograph is to be celebrated because it shows a beautiful world? And that a “manipulated” photograph is disappointing because they hoped it was showing us our beautiful world, but, disappointingly, turned out to be fantasy instead?

maiken,

I was stating a case strongly for clarity.

There is something in the example that you give. That person had obviously been taken in by looking at a holiday brochure at some point. Perhaps a common human experience when reality didn’t match the image.

However, I stand by my idea that we are creatures of habit. I wouldn’t think that this was controversial. Maybe it is.

As to fear of using the imagination…that is a little strong, but I can’t offhand think of another way of putting the same idea (hey, David, you are better at words than me…..). But there is something there, no? Some people delight in the use of the imagination and some people don’t. One isn’t better or inherently more noble than the other, but it does explain some part of the range of reactions to a work of the imagination. I am on record as saying that I’m not much interested in visual art based on imagination. And I don’t think that I’m alone. Anyhow, it is a range, and not two extreme groups.

David’s three headed dog is a usable example. I know people who couldn’t imagine why such a creature would be interesting or worth watching. I know other people who would go to see a film not otherwise well directed because of such creatures.

Have you ever put it to the people that you have discussed photo manipulation with that there is no such thing as an unmanipulated photo?

Have you ever put it to the people that you have discussed photo manipulation with that there is no such thing as an unmanipulated photo?

Yes, I often point this out. As far as I can tell, though, they seem committed to the idea that there is a reasonably bright line between a photo that shows “what things really looked like” and one that does not, and that they think less of the latter.

I think you’re right that when I explain that I intend for my photos to show how I saw a scene, this is comforting to them, becase it moves things closer to the “this is how things looked” side.

Maybe this is all simply because photos appear so strongly to be “just like reality”, that it’s a natural and automatic leap to the idea that they are faithful reproductions of reality? A sort of commonly-assumed contract between the photographer and his/her audience?

Maybe this is all simply because photos appear so strongly to be “just like reality”, that it’s a natural and automatic leap to the idea that they are faithful reproductions of reality? A sort of commonly-assumed contract between the photographer and his/her audience?

This reminds me of the story about Picasso painting a commissioned portrait of a woman. When it was done, the husband didn’t like it, and said “It doesn’t look like my wife!” Picasso asked “So, what does she look like?” and the man took a photo out of his wallet and passed it to Picasso. “She’s rather small and flat!” responded Picasso.

On the rare occasion that I get confused about reality and my photographs, I show my recent work to my dog. He loves me a lot, but he thinks my fascination with pieces of paper with colored patterns on them is utterly perplexing. He, at least, does not confuse reality and the photograph.

But Maiken is right. Try this experiment – dig out a photo of some recognizable thing. Find a person. Approach the person, hold up the photo, and ask “What is this?”

99 times out of 100, the response is “It’s a (subject of photo)”. Only 1 out of 100 will say “It’s a photo of a (subject of photo).”

David,

I think we should make “Did The Beatles Cheat?” the new tagline.

(hey, David, you are better at words than me…..)

Colin, you’re probably impressed because I do tricks with them. My most famous one is to use words as a lasso and pull my foot into my mouth.

I think we should make “Did The Beatles Cheat?” the new tagline.

Well it certainly would be the most cryptic one we’ve had :)

David

Colin, you’re probably impressed because I do tricks with them. My most famous one is to use words as a lasso and pull my foot into my mouth.

Well, it is a trick worth knowing how to do :-)

Here’s a post from David Byrne that relates to this old thread of ours: Crappy Sound Forever! Pretty interesting reading about how technology influences aesthetic conventions.