I don’t know why anyone would have a problem with it, but commercial art is cool.

All right, I do know why some people would have a problem. Working with clients can be ghastly. I remember saying these exact words to one guy one time, “Look dude, I’m not your art dog.”

“But I’m paaaaying you,” he whined while amazingly managing a smug smile, thinking, no doubt, that he’d just laid on me an argument for which there could be no possible riposte.

“You’re not paying me enough to **** your ***.”

“WELL! If that’s your attit…”

“It is. This deal’s off.”

So there’s that.

But most clients are much less demanding and far more appreciative, more appreciative by far and far more generous than your average gallery goer. You see, when you do commercial art, you’re helping someone else.

Usually, you’re helping them make money. That’s translates into money for you.

And the fact is, you really don’t get away from asshole customers when you do fine art.

I remember well another customer who’d commissioned a painting of Irises, giant, in a pseudo Georgia O’Keefe style that suited my temperament at the time. But she kept wanting me to change the colors after it was done. I accommodated her twice, but when she had me look at her bedspread and insisted I match it I said, “Sure.”

A couple of days later I invited her over to see the piece. It was quite large, four feet by two feet. I had it out on the patio on one of my steel display easels. It was a lovely patio too, a grape arbor overhead and in that summer, verdant.

“But you haven’t changed it!” She huffed.

“Oh yes. Watch!”

I tossed the half quart of alcohol I’d prepared, ready, and with a quick flick of a Bic, caused the painting to burst into lovely blue flames — just the color of the flowers on her bedspread.

I’d considered gasoline, but the alcohol, while not as spectacular, had the right color of flame. Also, one can put alcohol out with water. (I had some nearby.)

I laughed as she screamed, “You crazy bastard!” while running off.

It was hilarious. She actually waved her hands in the air.

Ironically, that incident helped my business because she talked about it so much around town. I got a reputation as a “real artist.”

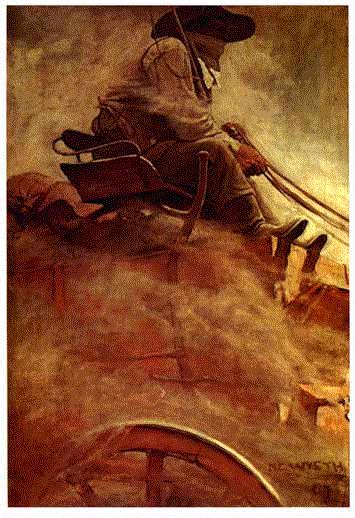

But client stories aside, the thing that attracted me to commercial art was that I generally liked the commercial stuff I saw better than the so called “fine art.” It seemed that fine art had been usurped by a not even middling amateurism while commerce and industry continued to insist, get, and put forth a higher standard of craft. I consider those gorgeous N.C. Wyeths in my beloved pre-teen books, like Treasure Island, The Deerslayer, and Robinson Crusoe and all those fabulous Frazetta covers of all those Edgar Rice Burroughs stories and I think, “The artsy fartsys are just smoked and they ain’t man or woman enough to admit it.”

So now I’m illustrating a book — back to my origins and the work that most inspired me. I’m now using a computer to cut and paste different drawings together because only the printed result matters. There’s no cheating. There are only results. Too much time spent burns the deadline.

I’m happy with my art. I like drama, excitement, and action in art. I’m bored to tears by what I see in the fine art scene, and speaking of tears, if I never exhibit in another gallery for the rest of my life, I will shed none.

One could do worse.

Commercial art is a blast. It’s fun to make. The best of it always transcends the original purpose of the commission. There’s a lot of money to be had, and I do like to make, as the French say “fun tickets.” Lot’s of ’em. You have a lot of freedom. I have no idea how commercial art ever got looked down upon by fine artists. Sour grapes, I suspect. Does anyone else have a clue?

Commercial art is at least easier to judge in that it probably has a well-defined purpose. The art you are doing for your book, Rex, has commercial intent also, but all the decisions are yours. Do you consider it in the same category as commissioned work?

Great points, Steve.

I love smart people.

How many of my decisions stick remains to be seen. We’ll see what my agent and publisher say. Generally, the idea behind book covers is: Does it make the person want to read the story? (And therefore buy the book.)

So though I’m originating the idea, it’s more in the commisioned arena.

Illustrations can have the same purpose as book covers, but in the case of an illustrated novel, the illustrations do part of the story telling. Like a kid, what’s happening is senior to what it is of; or, like a speaker of Latin, Greek, or Sanskrit my thinking is informed more by verbs than nouns.

Just popped in. I’m off to breakfast and my morning run now. Cheerio.

Rex,

I am not sure what your definitions in the 2 categories are. And why they would be pitted up against eachother. It reminds of the old high art/low art debate, as well art vs. craft. It seems like a cat chasing its own tail. I am aware of a snobbery toward some types of what you might call “Commercial art”, especially when I get involved with academic types. They are always on th e lookout for those dreaded “Sunday painters.” People can certainly be quick to snub their noses.

But in my mind there is huge crossover between what you might define “commercial” and what you might define “fine.” I see all sorts of crappy art as well as art I love, in both worlds (if I guess at how you distinguish the two).

What I will say is that I am also very glad for art that has no way of making money, that exists outside of the whole commercial system (not completely outside, because I don’t think any of us can be completely outside of the rules of economy – but that’s another story). What would Joseph Beuys do if “had” to sell his work? I think we would be at a big loss without some of his performances and ideas and they certainly were nto big money makers. But maybe those are just the ones that bore you to tears? It is hard to figure out just what you mean about the “Fine art” scene since galleries have such a huge range even within one city block! Are you referring to some personal experience of being dismissed as a commercial artist?

ps – remind me to hide my lighters if I ever see you in person!

Hi Leslie,

I think we actually fundamentally agree. Art vs. craft, high art vs. low art and the snobbery of academics. In another field, for example, I had a number of math professors tell me I would good engineer. It was meant as an insult.

I decided to not go on to graduate work in mathematics as result of that snob attitude. Besides, one of my favorite math heroes, Bezier (the same Bezier in “Bezier curves” — which any image editing or vector graphics program user will know), did his work in order to efficiently calculate how much sheet metal was required to make the curved surfaces of cars, and the math teachers were, as far as I could see, making zero useful contribution to the world outside their domain.

I too am glad there exists art that’s not for money, though I’m not familiar — in fact I’ve never heard of Joseph Beuys.

There has long been the ideal of the amateur. The Olympics are an ancient tradition with respect to that. Colin makes a very good case for that sort of thing, but the distinguishing thing is that good amateurs could sell if they wanted to, and people would buy. They just don’t want to.

So I guess that’s where I’m drawing the line. The definition of “commercial” I’m using is art that is used to help someone else make money. That means selling books, magazines, or some product. Good commercial artists have always managed to produce work that manages to stand on its own merit above and beyond that though. That is my personal standard of excellence. I do not consider a piece there until I’ve gotten that.

The personal snubs I’ve received have always come from over-educated non-representational artists, and I’ve come to just despise their whole psychology. I can spot them in a gallery usually before they even open their mouths. :)

Rex,

As usual, your stories make me smile!

Like you and others, I see worth in the highest forms of both endeavors. And I think that the enjoyment you get from working commercially (or alternatively, using your lighter to make color) must translate to your work.

Here’s where I think some differences (not better or worse, just differences) might lie.

As you say, it’s the finished look of the commercial art that counts — cut and paste in photoshop, whatever works to make that highly polished (or rough and ready) look that the client needs to put across her message. The product, to work as it is intended, has to be of the particular format required and often this requires a look that can translate into a flat medium, like a book cover or glossy magazine ad. In the very few classes I’ve taken where design was the focus, I found that I spent at least as much time, if not more, refining the presentation as I did doing the work.

In textiles (to move to a field I know far better than illustration per se) this means making the inside look as precise and finely finished as the outside. It can translate further into the standards set up by some long lost group-think — I’m thinking of the 12 per inch size of quilting stitches as well as their evenness. And of mitered edges. And batting that runs completely to the edge of the binding. and so forth.

What this results in is a squeezing down of materials that the artist can use — cotton doesn’t slip and slide and slither and stretch like silk. These standards insist that first and foremost the artist must consider the finished product — no jumping in without knowing precisely that you can achieve that spectacularly crafted look.

Now I’m perfectly happy to present that spectacularly crafted look, but I find that it can either interfere with the look that I really want (stretched and puckered silk is delicious but doesn’t photograph well and exhibit juries are confused by it) or that I become inhibited by the standards and blocked by the seeming impossibility of achieving it.

Someone once said “trouble shooting is easier than planning.” Somehow I think that illustration requires planning ahead, while fine art can wing it and sometimes exceed what illustration can’t.

And like Leslie, I also think you can refute everything I say here because the two fields are so full and encompass so much (and overlap at times, too).

For me, personally, the flat glossy perfection of illustration (or its equivalent, the high-end cotton quilt) is no fun to do. It doesn’t move my mind like the wonky irregularities that happen to come along as I struggle to achieve something else, something not intended to push a product or enhance a message.

Yes June,

The dividing line is personal pleasure. For me, that means passion. I have to have it. If I do, it comes through in the work; if I don’t, I just can’t fake it.

(Well, not for long, anyway.)

What you say about the joy of the frumpy unpredictability of random irregularities makes total sense. On the other hand, there’s a lot of commercial work that’s fantastically loose. Look at the art in CD jackets, for example. Pretty wild stuff.

Rex,

This Wyeth painting is interesting in the way it has such a strong chromatic impact with a limited palette. White and grays play the role of blue, for example, a do so effectively.

Look at the art in CD jackets, for example. Pretty wild stuff.

Seems to me there’s both good and boring stuff going on in “fine” and“commercial” art. By “commercial” art I’m assuming you mean advertising or illustration, as opposed to “commercial fine art” like Kincaid or that blue dog person.

Since commercial art is about selling something other than the art itself, the only kind I can get excited about actually doing is art that sells something I like. Music is shrinkingly in that category, in the sense that while I love music, the artwork keeps getting smaller. First there were album covers, then smaller CD covers, and now it’s whatever can be viewed on your iPod.

Hi,

I’m actually a student at art school and am writing an essay on commercial art vs “fine art”, and I found your opinion interesting. I’m basically of the same opinion. I think that the “fine art” world has become controlled by an elite few, mostly public servants who head state run galleries and government grant issueing bodies, and as a result all of the “talent” has moved to the commercial arts.

I was having a debate with my supervisor over this (we don’t agree obviously). My essay is specifically about Frazetta, comparing him to other great hero/narrative painters of history, of which there is plenty of precedent. My supervisor kept coming up with fairly lame reason’s why “my guy” (apparently commercial artist’s aren’t good enough for him to refer to them by name) wasn’t a real artist. He basically said that to be a real artist, you had to express doubt, anxiety, uncertainty, and explore problems. What a load of rubbish! That’s perhaps true if you’re an insecure loser who isn’t sure about anything.

Another thing I hate is the the “fine art” world is so snobbishly dismissive of any art that people like, i.e. true “pop art”, like comics, landscape photography, fantasy art, etc. The fine art world is of the belief that if a work is “too easily digestible” then it must be bad because it isn’t challenging or confronting. The belief around my school is that “real art” is difficult, challenges, and confronts the viewer – i.e. the viewer doesn’t like what they see. No wonder fine art has marginalised itself while film/tv has come to such cultural dominance.

anyway that’s my beef. if you have any helpful info please email me!

Rex – one my students posted a link to this post as part of his answer to a question in our online classroom about commercial art vs. fine art. I wanted to tell you I absolutely LOVED your story about the blue flames that so perfectly matched the customer’s bedspread! As someone who has straddled both the fine art and commercial art fields I applaud your astute observations.

wants a differnce between commercial art & applied art

Hello Rex,

Personally I think – after read all the arguments/debate above- I find the conclusion. As a live human. “Art much less important than life, but what a poor life without art” (Unnamed)

There’s no real “fine artist” without body and soul. There’s no body without foods.There’s no foods without money.

Fine art is only for art sake. Even a gallery try to exhibit it’s fine art work aims to show it to the peoples due to this gallery reputation, event, prestige etc… so it’s already miss from the first rules.. “Only for art sake”

and for e fine artist too..

try to live and works in third world country with it’s fine art skill only..

I guarantee soon the artist will be dead in poverty; no foods, no beverages etc..

So fine art is very complicated and almost not possible to do for poor artist even he is talented in art..and I agreed with Dan notes above :

“I think that the “fine art” world has become controlled by an elite few, mostly public servants who head state run galleries and government grant issueing bodies, and as a result all of the “talent” has moved to the commercial arts”

it sound capitalism system influence art. Personally I don’t like it.

I more agree that we have a GIFTS from God -or nature if you’re an atheist- it’s our TALENTS… or ability to create something… for life it self ability to paint…and if “a fine artist” refused a commission art because his idealism about “Fine Art” when actually he really needs money for: his wife medication, pay the house rent, pay the kids school, pay the bills etc… and he able to do it easily… but he don’t…

Yes maybe he is a Great Fine Artist for some peoples… but for me He is the most stupid person in the world… stupid father.. stupid husband.. etc..

I found lot of case like this is my country.. 3rd world country. Lot’s of fine artist divorce.. abandoned his wife and children..living in a dirty flat.. sick.. eat Geckos for survive… no foods..no money… and dead terribly…unleash you are son of Donald trump or Bill Gates may be this will not happen… :)

Rex you choose the right decision. :)

http://high-end-skills.deviantart.com/

Life: For Art, By Art, for Art..

thank you,