I’m still reading Pessoa, especially his Alberto Caeiro persona, my favorite, who has a seemingly clear and simple view of the world and our experience of it. According to Wikipedia: “Central to his world-view is the idea that in the world around us, all is surface: things are precisely what they seem, there is no hidden meaning anywhere.” Suppose we accept this for encounters with the natural world; how can or should we apply it to looking at art? Can a river, a tree, a rock in an artwork be as innocent of meaning as in nature?

In the spirit of June Underwood’s idea of gathering of A&P contributor artworks to let them “chat” with each other, I’ve gathered a few here to let them also converse with Caeiro/Pessoa. I’ll start with poem 39 from “The Keeper of Sheep,” translated this time by Peter Rickard (original on this page).

Where is it, this mystery of things?

Where is it, and why doesn’t it at least

Appear, and prove that it’s a mystery?

What does a river know of this, what does a tree know,

And what do I know, who am no more than they?

Whenever I look at things and think of men’s thoughts about them

I laugh like a brook coolly babbling over stones.For the only hidden meaning of things

Is that they have no hidden meaning at all.

It’s stranger than strangeness itself,

Stranger than the dreams of all poets

And the thoughts of all philosophers,

That things really are what they seem,

So that there’s nothing to understand.There! That’s what my senses learned unaided:—

Things have no meaning: they have being.

Things are the only hidden meaning of things.

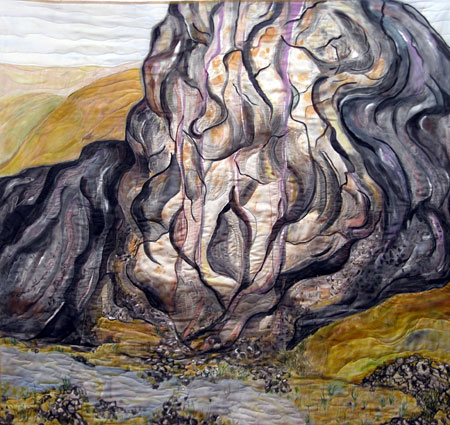

reflections on the south fork of the sacramento by Rex Crockett

Mother by June Underwood (updated -SD)

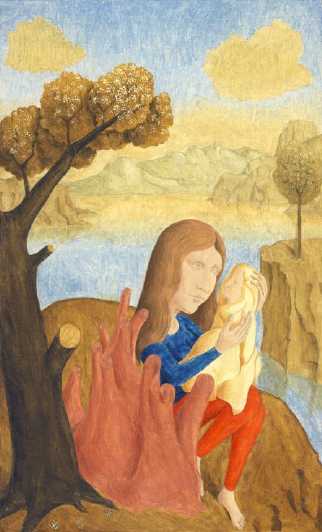

mother and child by Karl Zipser

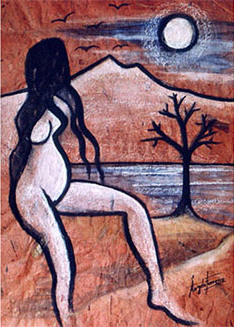

Mother Water 2 by Angela Ferreira

The natural elements in these works seem to serve different purposes and to lie in different places on a literal to symbolic spectrum. Is it possible to view them in a way consistent with Caeiro’s “no hidden meaning” philosophy? Is it possible for an artist to view even the natural world in that way? What changes from the rock you see to the rock you draw or paint or photograph?

Is this the opposite of what Sunil talked about in his post on symbology?

Things have no meaning: they have being

This would require viewing something without an emotional engagement (this tree makes me feel like…), a professional engagement (this tree needs to be fertilized to bear fruit), or horticultural sentiment, nothing.

Our limbic system is full of peptides that make us feel excited, motivated, depressed. How can we view anything without having a feeling about it. It is worse, I cannot even think when I look at a Douglas fir in Michigan that is native to the northwest.

The moment that we notice something we put it into our world view and it acquire a meaning for us.

Birgit,

I think that’s a very natural response. And humanly and neuroscientifically speaking, maybe we cannot help but assign meaning to anything we notice. But the poet’s ideal seems close to some concepts of Zen Buddhism, and that kind of attitude is often considered desirable. Even if unattainable, is this something to strive for?

In his last post before today’s, Doug Plummer said this about his photographic approach with his favorite subject: “I am able to let go of the conscious attention.” That seems like close to the same idea.

Maybe that is what the music is doing for Mark.

I will think about it some more.

I took a walk, looking at different trees. What you said made more sense when thinking about it outdoors. Earlier, while typing my first comment, I looked at pieces of nature that I had collected and brought inside. I saw these pieces as ‘symbols’ of nature rather than as ‘beings’. Later today, I will attempt to look at the geraniums on my windowsill as something that is rather than something that gave us joy throughout the winter.

Is there a difference between painting or doing textiles from imagination and photographing? Is a photographer less of a ‘filter’ for what there is than such a painter or textile artist?

I do not know much about Eastern philosophy. Could one assume that the painter and textile artist in this case are a part of nature?

Steve,

I think this extremely simple idea is the hardest, most complex state to achieve. As Birgit says, one sees a flowering pear and thinks “spring” or “fertility” or “beautiful.” What Pessoa/Caeiro are perhaps advocating is not putting words to the emotions — to feel without words, to observe without labels, to examine without prior or forward thinking. It’s harder than hell to do. Sometimes you can do it if you interpose white noise (“Oooommmmmmm”) between you and language, so you are just looking.

I like playing or attempting to achieve the non-being, the giant eyeball that Emerson talks of, but I am also in love with the expansiveness of observing with words and paint and thread — expanding beyond the immediate recognition to something that encompasses more and more. That probably doesn’t make sense or sounds pompous — sorry. But both ends of the continuum — total immersion in the thing itself without words or symbolism through to the other end, the kind of evocation of a day that James Joyce’s Ulysses manages to bring about, are almost like full circles — they both fling us out of our usual habits of mind. Isn’t that part of what art should do, also?

Of course, the pieces you show talk to one another and thereby violate the silence — even the titles keep resonating with me: “Reflections” with its double meaning; “mother” is loaded with multiple “meaning,” “mother and child,” “Mother Water 2” — these all push us to interpretation. To see as Pessoa/Caeiro recommends, one can’t have titles. Is it possible to see Angela’s piece without the title? If so, what does one see? And does that relate to the other “mother” images. Or is comparison an automatic interpretation and therefore not an approach that would work?

I always have too many questions when I’m faced with such ideas as P/Q presents. And questions, of course, are interpretations, which I should eschew. I can see the beauty of what he advocates, but I have a hard time not labeling that pear tree beautiful. And then, in my more cynical modes, I think that the person best suited to observe as P/Q recommends is someone with Alzheimers. And that thought stops me cold.

And on the final hand (I seem to have many hands this evening) thanks for bringing up Pessoa again. Right after I finish with my STeve Edwards books, I’ll have to take up the poet in his many manifestations.

Birgit,

I think that if you look solely at the painting or textile and don’t reference the reality that it might refer to and don’t think about process or paint or stitching or color — that is, don’t put words to those items but just let the art pour over you — then you are indeed reacting as if the art were part of nature — part of the mystery.

Again, I really find it hard to do — although rewarding if I can manage it. But I can only manage it in short bursts and I find it exhausting to keep my “mind” at bay — it always drifts back in. It’s like that story where the demon wouldn’t destroy the family so long as the adolescent child didn’t think of the people that the demon wanted to destroy. Knowing this made it almost impossible for her.If I’m remembering correctly, she thought of bricks, in detail. Even that takes a discipline that could be beyond me.

It’s me again — I’m trying to hear the conversations among the group of works that Steve has assembled.

It sounds to me like they are all playing with “mannered” landscapes — pointing at the real thing but always moving into another state. Steve’s image of moving water, for example, stops the flow. We know that that wonderful white stream is wild white water, but while the image allows us to believe that, it also forces us to think round pillows, softness, snow, paths to mysterious places. And Rex’s “Reflections” is another scene that we could say we recognize, but instantly it turns strange. The lines and shapes have their own rhythms and compositions, the shadows on the shore hide things, the rocks look soft.

And so forth. The discussion among the landscape elements might be something like “look at how silly humans are — they look for 30 seconds and move on and fail to see anything at all that’s right here.” Or the conversation might be more philosophical: “Parental privilege, human responsibility, what are these in relation to the objects we find around us?” Angela’s seems to me to be asking questions, Karl’s family in the midst of the sawed off limbs, my rocks looking soft and bent over and calling themselves Mother — anyway, I’m just maundering about some ideas. I wish I could see these side-by-side and play further with their conversations. My Rock seems to be listening to Karl’s mom and kid while Angela’s Mother looks either toward us or away at something distant and seen only by her. And Rex’s stream just observes what’s happening, while Steve’s stream hastens on, oblivious to anything in its way.

June,

I love your insight about mannered landscapes. Although Karl’s and Angela’s could be seen as using trees and water in a way that’s both symbolic and reminiscent of old masters, similar things could be said about my photograph. Is my stream more realistic? The motion blur captures one aspect of how we would experience it if there, but it also abstracts over details in the stream we would also notice. (I like how you see the stream as pillows and how in Rex’s drawing the rocks are the pillows and in your piece both the mother rock and the stream are of pillows.)

And looking at the stream, as you say, we are led to other places. The stream stands out as a path, a potential journey toward the source that we might undertake (and I did, partway, the day after this evening shot). Perhaps Angela’s woman is contemplating a similar journey, or a more personal or spiritual source. In your fabric piece the stream is small and overwhelmed by the rock, but the rock itself is a vertical stream that looks like my stream upended. As if that rock is flowing up out of the earth. Which, in a slow-motion dream-geological sense, it did.

The poem distills an idea of Pessoa’s, but it was chosen as much for the mention of river, tree and stone than brings together the artworks, which can have further conversation with the poem and each other. Although I think there’s much merit (artistic and otherwise) in sometimes seeking a kind of mindlessness, I also think the mere existence of the poem proves we can’t not look beyond things. We can’t not hear, in the sound of a brook, a human babble or a laugh.

Meaning is something we bring to things. I don’t think the natural world has any meaning at all, hidden or otherwise. But I disagree with Pessoa that the absence of meaning means there’s nothing to understand.

Steve,

To add to the meaning of “Mother” — the big looming rock was literally upended from its burial deep in the earth. It’s the oldest non-exotic terrane in the Fossil Beds and is composed of rounded streambed rocks cemented over the 80 million (give or take a few)years that they lay together. The stream originated in Idaho, some miles east. This is the only rock of its kind that the geologists have located in Oregon, which is, in its other formations, 20 million or so years younger than “mother.”

The real title of “Mother” by the way is “The Mother of Us All.”

David,

I’m pretty sure I agree with you, but this might be a place where words (like meaning or understand) are almost squishier than visual art. It’s hard to disentangle what’s with the viewer, what’s between artist and viewer, and what lies with the larger culture.

So, avoiding semantics, can you contribute one of your works to this exhibition? There are certainly some of your recent ones (like Flatlands #51 from the interview) that suggest rivers and how they are on the earth. Is there one that helped you understand or express something about rivers or trees or rocks?

Rather than contribute an image, I’m recommending a book.

Seeing Is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees: A Life of Contemporary Artist Robert Irwin

I had puzzled more about the water than the rocks in Rex’ picture. Now, after reading June’s comment on the soft-looking rocks in his picture, I could imagine being in the water that is rushing by the rocks, similar to being in a fast moving train looking at the blurry world outside.

I remember a picture in an earlier post by Rex showing a man riding a fast coach. Rex is high energy.

About June’s new picture, I love the combination of yellow and purple/lavender.

I see a mighty woman sitting down rather than a rock.

The picture also reminds me of Bob’s tulips . Both June’s purple ‘being’ and the tulips have their tops cut off. Some of us already discussed the effect of cropping with respect to the tulips.

David,

That looks like an interesting book, I love the title. I experienced one of Irwin’s signature pieces, “Two Running Violet V Forms” (which are actually quite blue, maybe the red faded quickly) frequently over six years at UC San Diego. I thought it was OK, but I liked the lead-covered fake eucalyptus trees in the same area better. They played music or read poetry that you would catch a bit of as you walked by.

Steve, the trees you mention are by Terry Allen, a very interesting sculptor and country songwriter.

If you make it to Los Angeles, be sure to visit the garden Robert Irwin designed for the Getty Museum. I don’t even go into the museum anymore – I head straight for the garden.

Lawrence Wechsler is one of my favorite authors (he wrote “Seeing is forgetting….” so I ordered it right up from Powell’s.