About a year back a young curator named Chris Gilbert resigned from his job at the Berkeley Art Museum, California over a disagreement with senior museum officials over some ‘politically incorrect’ words that he used to describe the exhibit that he was curating. I am sure that this is old news to all of you, but what got me thinking about one of the functions of art was through reading a contemplative piece in the Times where author makes the following observation:

Two concepts of what a museum should do — and be — crystallized and clashed, with Mr. Gilbert’s view by far the less traditional. To him, art is an instrument for radical change. The museum is a social forum where that change catches fire. The curator is a committed activist who can help light the spark. The goal is to transform the values of the culture that had created the museum. If in the process an obsolete museum went up in flames, a new one would rise from its ashes.

This post is not to resurrect Mr. Gilbert’s politics or to rake up old wounds but to discuss about how many of us truly believe that art currently is functioning as an instrument of radical social change (if not radical at least some social change). How many of us believe that art educates us and chides us on our society’s little foibles? That the value conferred by art can be measured more by its inherent beauty / message than by the greenbacks that it can command?

In fact, the more successful a museum grows, the more elitist it tends to become. Social distinctions based on money and patronage can assume the intricate gradings of court protocol. At street level, admission prices climb, reinforcing existing socioeconomic barriers. Programming grows more cautious. If you’re laying out $20, you want to see “the best” art, which often means art that adheres to conventional versions of beauty, authority, “genius” (white and male) set in a reassuringly familiar context.

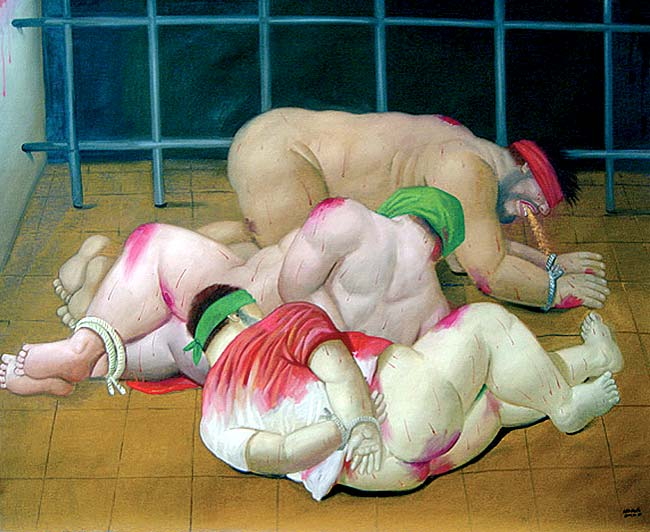

Painting by Fernando Botero; Title: ‘Abu Ghraib’; Material: Oil on canvas

Sculpture by a contemporary artist: Title: ‘Domination’; Materials: Railway track, wax apple, plastic crocodile and glue.

I would be interested in your thoughts…

Though I can see Gilbert’s point of view, the irony is that he could probably have made his point much more effectively if he had been less dogmatic about it. It seems naive to expect art museums, dependent on public and private funding, to go too far to deliberately offend audience and/or funders (I’m speaking in general, not about the specifics of the Berkeley case). I think this is one area where the Internet, where the cost of setting up web galleries is relatively low, can make a difference.

I think of the mission of public museums as being to educate and provide access to art. The notion of balance should be construed broadly. Not each exhibition necessarily, but the overall set of exhibitions should have reasonable balance. Maybe museums should be like universities, with something like tenure to promote academic freedom?

I only hear about male curators. Are there any women in that field?

Steve,

I guess you are correct that museum curators need to abide by cultural sensitivities and abide by certain common laws that are deemed ‘politically correct’.

However, in addition to them functioning as citadels of education and access to art, museums could play a bigger part in educating people about impending issues of the day and curators are the agents of this change. A case in point is the strange incident where not a single museum in the United States was willing to take on Botero’s Abu Ghraib works until late last year (http://www.theartnewspaper.com/article01.asp?id=443)

From the article (27 Sept 06):

Colombian artist Fernando Botero is offering some 80 paintings and drawings portraying the abuse of Iraqi prisoners by US soldiers at Abu Ghraib prison to any suitable museum willing to display them. Despite the generosity of the offer, Mr Botero may struggle to find a home for his Iraq cycle. He says an exhibition of the works was “proposed to many museums in the US, but after six months there was no interest.”

I like the idea of tenuring that you proposed. Are you talking about tonsuring the museum itself or the curator (like professors in Universities) or an exhibition in the museum… ?

Birgit,

I found the following study to be a little useful on the subject of women going into curating as a profession but did not run into any prominent names..

http://depts.washington.edu/coe/cirge/pdfs%20for%20web/arthistory/arthistory_report.pdf

Of course for a healthy dose of ideas about women in museums I always turn to the blog by Edna the self professed Anonymous Female Artist (a.k.a. Militant Art Bitch)…

Sunil, I don’t know how to put images into a comments. therefore, I did a post, see above.

Sunil,

Don’t correct that typo — I love the idea of shaving the curators or the museum itself. The curators already consider themselves priests… As far as tenuring, I meant: treat curators like professors.

I’m shocked about the Botero, I would have thought at least some university museums would have been willing.

I’m afraid I don’t get the Domination sculpture. Is there something controversial about it?

I am laughing loudly right now – at myself…

I did mean tenuring and am really not sure how I got tonsuring… I will leave it as it is – levity is good… (I think I know how – every once in a while I spell check the response on outlook and then paste it in here… an old habit that gets the better of me)

Your idea about tenuring curators is a great one (maybe a post on that some other day) – I am sure if the curators hear about this idea they would get ready to tonsure us…

The domination sculpture was included to contrast the Abu Ghraib. (While one is full of meaning and could shame us, the other is superficial and flat containing little inner meaning). Both done by artists of today.

Birgit,

Your post is thoughtful and a useful contrast.

Sunil,

Who is the artist of the sculpture and what do you know about its meaning? I don’t get the meaning behind it but I did see it as playful and was wondering about its connection to Botero.

Steve,

I think museums and galleries have room to be more edgy or controversial than they give themselve. Maybe not the Smithsonians of the world, but the more independent ones or University galleries. I think they underestimate the public’s interest in certain topics. Didn’t Mapplethorpe’s famous exhibit in Ohio have record crowds after all the hoopla?

I also think there is a way to cover controversial topics that challenges viewers wihtout force feeding them.

Leslie,

Agreed. I think anyone showing Botero would now be seeing it as a very smart move.

I sort of like Contemporary Artist’s work. I really cannot make sense of it but the three elements seem to belong together, simply posed and balanced, yet strangely related in size and scale and material. What is your take, Sunil?

Botero’s work is what it is; for me, another reminder of the atrocities. I am perplexed by the figures’ rotund form, how they are more “Botero” than “Middle-Eastern”. Why?

As to tenure for curators: mistake! The university museum is already too closely tied to Alumni matters. Besides, I like making them sweat as much as possible whenever possible, unless, of course…

White skin on the Abu Ghraib’s prisoners is akin to the brown skin on the Sweet Jesus – doing away with stereotypes.

Oh bully. A topic after my own heart. (That post is coming, Steve, I swear!).

You want to know the reason no museum would show Botero’s work until recently? Political winds are fickle and can blow the money right out of your hands. The museums had to make sure that the audience would be receptive. After November 2006 it was deemed “safe” to show controversial work that dared to *gasp* question the morality of the war because the American public voted (most of) the war-mongers out.

As Steve said in the first post: Museums can never be the purveyors of the avant-garde. They are monolithic, traditional storehouses. Though some may try (and succeed to some degree) to show cutting edge stuff, the true avant-garde will always be looking for an avenue that conflicts with the museum structure. It is the nature of the avant-garde,indeed the nature of what makes contemporary art relevant. Art is not supposed to make the masses go “oooo”. It is supposed to shock and challenge society. Though the public at large will surely be exposed to new ideas in a museum, most artists and art lovers have seen all that shit before. The galleries, alternative spaces, and the street are where the freshest, most important work is being shown and seen.

Dig:The museum is great for study; the street is where the change happens.

Art as an instrument for radical social change. Hmm, I guess that depends on what you mean by art.

I would say, yes, sort of. But it is not the art in the museums, obviously, and it is not the stuff called art. And it is not always the intent of the stuff to cause radical social change.

For example, commercial pornography is produced to make money. I classify it as art (sorry folks) because it is clearly a visual representation of something important to people at an emotional level. Good art? Maybe not, maybe sometimes. Throughout history, images of male and female have been created through an artistic process that involves idealization. But photographic pornography, despite the selection of the most ideal models available, and a lazy attempt at arty effect, presents a radically new and realistic representation of human sexuality. That will, over time, have a huge effect on how people view themselves. A good effect or a bad one, I don’t want to speculate. All I am saying is that pornography (which used to be illegal of course) is an art form (not recognized as such) that will produce radical social change, because it will, with time, radically change the way people view what it is to be human.

Leslie,

I took the picture of the ‘Domination’ sculpture at a community art fair in NJ recently. The artists did not want to be named and said that he created it as a parody on the meaninglessness of some of the current artworks presented. When pressed for deeper meaning he said there was none and he decided to do it on a whim with found materials. I thought the sculpture was a useful contrast to ‘meaningful’ works like Botero’s…

D,

I liked ‘Domination’ because it seemed so random. Yes the materials seemed to fit together but it seemed just arbitrary… Yes, even I cannot make sense of it…

Karl,

It is strange you mentioned pornography and its effects on people in this context. I was reading the following essay on the importance of pornography and its relation to everyday life just yesterday… http://bad.eserver.org/issues/1998/38/duff.html/view?searchterm=pornography%20latin

It is funny that you were thinking along the same lines…

Sunil,

I enjoyed this post and the description of the nutty curator. It suggests to me that there are people in the art world even more confused than I am!

Thanks for the porn link. We have had about 6000 porn spam messages to A&P so far (almost all caught by the automatic spam filter) but somehow I doubt that this essay was among them.

I’ve done an interview with a Dutch porn CEO on the topic of commercial porn and art. I’ll hopefully be posting that soon.

Sunil,

Thanks for the update on Domination. I guess by not being able to get it I got it. Sort of.

Art is not supposed to make the masses go “oooo”. It is supposed to shock and challenge society.

I don’t agree. Art can be challenging and shocking. It can also make people go “oooo”. (Sometimes it can do both at once.) Both are useful functions, and art would be all the poorer if we ruled either out a priori. If all art (or all art to be taken seriously) violated the status quo, then that would become the new status quo. Art is what is and artists will do what they do, which is the way it should be.

If all art (or all art to be taken seriously) violated the status quo, then that would become the new status quo.

Arthur,

Isn’t that exactly what we have now?

Sunil, some observations on Botero:

I am astounded that so many have weighed in — and continue to do so — on the refusal of various (unspecified) U.S. museums to take the Botero show, while so few have bothered to approach the museums themselves to find out why that might be.

I am aware that, in late 2006, Botero’s gallery offered the exhibition to several Bay Area museums with the requirement that it be exhibited in January or February 2007 to coincide with the artist’s planned visit to the region.

No major museum works on so short a schedule. Exhibitions are typically planned years in advance, and to cancel scheduled programs would mean a considerable financial loss.

And yet this fairly obvious aspect of museum practice (that it takes considerable amounts of time, energy, and planning to prepare and present an exhibition and the programs, catalogues, and so forth that accompany them) seems to have been left largely unconsidered amidst the (often righteous) commentary that has surrounded this collection of paintings by Botero.

Then there is also, of course, the question of whether or not the works actually merit a major show. Politically contentious subject matter doesn’t automatically constitute great — or even interesting — art. As appalling as the torture at Abu Graib was, that fact in and of itself should not necessarily be the principle upon which decisions are made about what belongs in an art museum and what does not.

Chris Thompson’s article on the exhibition provides an interesting perspective.

– R

Rod,

Thanks for the input, I had also been thinking about the scheduling issue, without knowing about Botero’s explicit requirements. But, quality issues aside, I would have thought that museums could at least temporarily (one month?) carve out some space from their permanent collections if they wanted to. From your perspective, do you know how easy or hard that would be to do?

Rod,

Thank you for your views.

Botero’s work was an example whereby I was trying to highlight the part that museums and curators can play in developing ideas about social change and comment on social perceptions.

The article that you pointed out is indeed interesting especially the following quote by art critic Jed Perl

Botero’s pieces “had as much sense of form and structure as mushy brown gravy poured over marzipan.”

“Botero appeals to an old-style philistinism, to the idea that works of art should have meanings so obvious that they grab you by the lapels. Perhaps any stand in art now seems better than no stand at all, and never mind the art.”

I find it strange that people now refer to art with meaning as “old style philistinism”.

I also found the following comment in the same article fascinating on how the artwork at least got some people thinking about societal perception and drawing analogies (which should be one of the functions of meaningful artwork):

“Almost none of the writers commented on the artwork itself; instead, they almost exclusively focused on their political views.

“This is so sickening,” one wrote. “Of course, it happens in the US every day, especially regarding African Americans and immigrants of color.”

Steve –

>But, quality issues aside, I would have thought that museums could at least temporarily (one month?) carve out some space from their permanent collections if they wanted to. From your perspective, do you know how easy or hard that would be to do?

How easy or hard it was would ultimately depend, I think, on how badly the institution wanted to show the work. It would not be impossible, by any means, but there would certainly be (unbudgeted) costs associated with de-installation and installation, art storage, and so forth.