Painting From Life vs. From Photos

Drawings, paintings and photographs all seem to be more or less static entities. With luck, they can last more or less unchanged for hundreds of years. It is therefore interesting, if disconcerting, when artworks appear to change drastically from day to day.

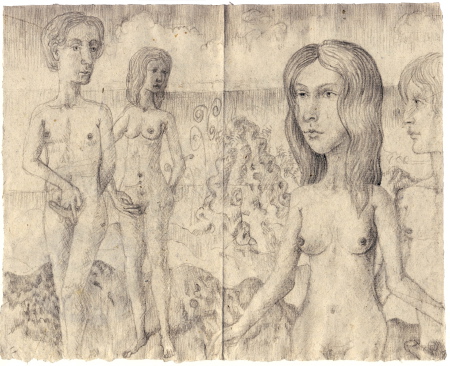

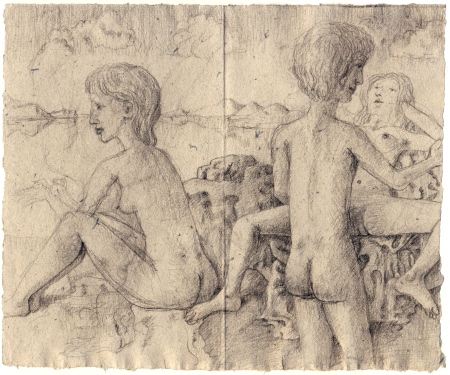

This sense that images are changing “on their own” was something I experienced with a recent drawing series on my handmade paper — the pictures below are a sample.

After I “finished” the series of ten, the drawings seemed to change each time I looked at them. Sometimes I was pleased with the result, other times I was unsatisfied, disappointed in my work. Why was everything changing, as if by itself?

One important factor was context; what order did I put the pictures in, what was the background? I spend a lot of time ordering and grouping the pictures to try to find combinations that worked well together. But even when I had the images in a set arrangement, I still found the results unstable: sometimes I found the images fascinating and would stare at them for a long time. The drawings seemed grabbed my attention and I had the feeling of being on the verge of learning something, of seeing something for the first time — the tantalizing feeling of being on the edge of discovery. Other times I didn’t like the drawings at all and couldn’t see anything in them. What could be going on?

After some thinking, I remembered that pictures that “change” by themselves are a well known phenomenon in psychology. For example, I remembered this image which I had studied during my days in visual science:

Can you see what the image depicts? If you can, you will always be able to see what the image represents, and it will be quite clear. If you cannot decipher the image, it should seem to you like a bunch of random spots. If, after looking, you then decipher the image, it will have permanently “changed” for you. This example was interesting to me with respect to my own drawings, but it was not a clear match obviously. I could see the forms in my drawings. The drawings changed repeatedly as well, not only one at a moment of recognition.

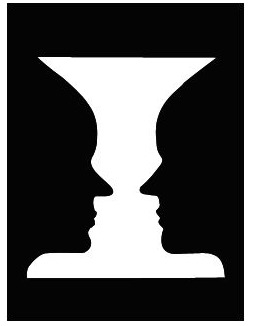

Below is another example of an image that changes. The image can be seen in two ways: as a pair of faces looking at each other, or as a vase. This famous illusion has the property that it will continually change with viewing; sometimes it appears as two faces, sometimes as a vase. There is no final stable state, as with the spotted image above.

Neither the faces nor the vase remain permanently dominate — that is the way the image is designed. The figure-ground relationships will continually shift. Below is another example of a multi-state picture, the rabbit-duck image. The drawing can be seen in two ways, but not both interpretations are possible at the same time.

These textbook examples show transitions between 1) no form (spots) and form; 2) figure and ground (face/vase); 3) two different interpretations of a figure (rabbit/duck). The transitions can either be oscillatory, or a one time transition. [These textbook examples are online here and here.]

Thinking about these images made me wonder if I have inadvertently made multi-state images as well. If so, the states are not as clear cut, and the transitions are not a simple match to the three textbook examples. The part that I find most interesting to think about is, what domain or domains are traversed when I see my own drawings in different ways? The concept of figure and ground is essential to understanding what is happening with the face/vase example. What concept (perhaps it doesn’t yet have a name) would I need to classify the changes that I observe with my own drawings?

Do you frequently experience this phenomenon of artwork apparently changing on its own? Does it occur more with your own work, or with the work of others? Is it better to try to make “stable” artwork?

The old Karl is back! Can we see blow-ups of the second and third picture to see them better?

One of the things that I’ve learned in studying painting and drawing is that the design of negative or background space is as important as that of positive or foreground space. I assume this a common lesson. So I would imagine that figure/ground reversals come more easily to those with formal training in the visual arts.

It’s not just an artwork that changes with mood or things you might be attuned to because they’re “on your mind.” Don’t you have some days when everyone looks seems to look great and others when the whole world’s ugly?

Regardless of the reason, it’s considered a hallmark of a great artwork that one can keep going back to it and seeing different things in it. And I think the capability to do so with your own art is definitely a plus. Too single and narrow a view is likely to result in boring work.

Optical illusions totally catch us off guard.

I wanted to mention a prime example of my work changing it’s meaning. A few years ago, I made work that I thought was invincible–it was never going to change. Then two years ago, I came out as a gay man and suddenly all my artwork changed–but they looked exactly the same! I could go on and on about the little details. But overall, my work is effected by the slightest change in my identity (because my work revolves around my identity). Just imagine being in the closet, and questions arise about your work being a bit ‘homosexual’. I would deny, deny, deny! Or at least, say ‘sexuality’ is not an issue here, and that I was focusing on other topics (going as far as to discuss the importance of the ‘third sex’ in art). It is completely strange to look back at my work created during that period of time when I wasn’t comfortable being myself because the original meaning–as solid as it tried to be–does not shine as brightly as the meaning it emits today.

Karl,

Refreshing to see your paintings exploring the same theme again. Rather than touch on the topic of illusions, I would like to focus a bit more on these latest works by you. What are you trying to say via these? Are these part of a larger work and purely exploratory in nature? Have you devised any color scheme for these (I remember the hills and valleys flanking the nudes from before)… Does the first one represent scorn for pleasures of the flesh while indulging in self inflicted masturbatory fantasies…? I am not so sure what the second one means…. Tell us some more. Some higher resolution pictures would be most useful…

Karl,

As usual, your post made my mind go madly in many directions.

The materials on multi-state images I was somewhat aware of, but not to the extent that you discuss. In themselves, these images and attached ideas are fascinating.

And Steve is correct in saying that we look at our own word differently from day to day. The personal attachment that we have to our own work — we can feel the line of the pencil on the paper — makes our vision of it absolutely peculiar — and changeable, because our relationship to it is so close, so intimate. I like it that you said “But even when I had the images in a set arrangement, I still found the results unstable: sometimes I found the images fascinating and would stare at them for a long time. The drawings seemed grabbed my attention and I had the feeling of being on the verge of learning something, of seeing something for the first time — the tantalizing feeling of being on the edge of discovery. Other times I didn’t like the drawings at all and couldn’t see anything in them.”

Ultimately, of course, art, like rivers, aren’t static. You can’t step into the same river twice, you can’t read the same book twice, and you can’t see the same painting twice. Not only does the context (as you describe with your own work) change — seeing the work in a gallery, in a book, with many other pieces hung beside it, placed on a wide white wall all by itself, etc — but you yourself change from minute to minute. Someone steps on your toe trying to get a better look, you are two minutes or two months or two decades older. The art work may stay the same in a Platonic sense, but we can never know its Platonic nature– we can only know it as we move through our existencies, living entities which never remain static.

I hope we see more of these ten.

T.J. Clark’s The Sight of Death: An Experiment in Art Writing is all about how paintings seem to change over repeated viewing. Clark viewed two landscape paintings by Poussin over the course of years and recorded his changing reactions as an experiment. I didn’t find his experiment particularly successful (my review of the book is here: http://artblogbybob.blogspot.com/2007/05/sight-of-frustration.html), but the experiment itself was interesting. At the very least, he proves that paintings and what they “mean” are anything but static.

–Bob (ArtBlogByBob.blogspot.com)

Bob stole my comment; I’m just reading Clark’s book now. I’ll have to read the review to see how success is defined, but so far I’ve found it successful in leading me to think about ideas, as they relate to other artwork, that I wouldn’t have otherwise. I’ll add a comment to the Books resource when I’m done.

You wrote: “Thinking about these images made me wonder if I have inadvertently made multi-state images as well.”

Ofcourse you have. These images you made are representations of something else (the actual world or another representation). However, there is not a one-to-one mapping between the representation and the thing that is represented. It is in the difference between the two that lies the meaning of the representation. When looking at your images this process doubles. The representation of the image in your head is not the image that is in front of you. How can you be conscious of the difference? How can you be conscious of something that is not represented? Something that has no representation we cannot perceive as ‘something else’, but only as a difference of representation to earlier representations. We have to adjust our representations continually because our cognitive system expects differences. The breadroll that I had for breakfast this morning differs from my representation of it, because my representation does not coincide with my earlier representations of breadrolls. My representation of this breadroll this morning is changed, however slightly, and it is this very small difference that makes me conscious of the difference between representation and world. Even stronger, it is this difference that makes all of our consciousness. The real world we can only be conscious off by antagonism between our representations of it. So perception is continually trying to adjust representations to allow for the difference….thus part of perception is remembering earlier representations. Your changing subjective reaction to your images thus relates to the structure of the representational process. You consciously know that the actuality and your memory does not coincide. Therefore the images may seem strange to you. Because the actuality of an image always sligthly differs from your memory of it, the image can seem to be slightly changed. When you changed the context (order) of the images, you manipulated the amount of difference that your system had to resolve and therefore you changed their meaning. Might I point to Nelson Goodman’s study ‘Languages of Art (1968) that describes this process and to Umberto Eco’s ‘A Theory of Semiotics’ (1976) that formalizes the theory.

This theory also has some bearing on your “homunculus barrier”, wich, as I understand it, is commonly known as the “symbol grounding” problem (Harnad, Stevan (1990). The symbol grounding problem. Physica D, 42, 335–346.). Can be found on Wikipedia.

Thinking about this kind of things you wonder why one would ever need drugs to give your head a twist.

You also wrote: ‘The part that I find most interesting to think about is, what domain or domains are traversed when I see my own drawings in different ways? The concept of figure and ground is essential to understanding what is happening with the face/vase example. What concept (perhaps it doesn’t yet have a name) would I need to classify the changes that I observe with my own drawings?’

I suggest that the domain you traversed is the narrative structure. By changing the order you changed the narrative structure that is part of the representation of viewing your images consecutively.

This alters their meaning and therefore their perception. And vice-versa.

Karl:

Steve has a point. Ed Henning, once curator of contemporary art at the CMA, would comment about this. some days he would find the art in his galleries engaging and, on others, dull. Same art, different Ed.

Op Art fits in here. People like Victor Vasarely and Bridget Riley created canvases that engaged certain perceptual functions. For me, these pieces are for looking, but not for living with. Up the scale is another level where expectations based on memory are confounded The usual suspects would include M.C.Escher, Salvador Dali, that Baroque guy who made figures out of fruits and vegetables, among others. At the tippity top is Cubism, an epochal visual synthesis. Here one can find a firm and vibrant ambiguity of construction that engages everything you got. And a lot of it came from Cezanne.

Me, I can’t trust my own first impressions. So many times I have stepped back beaming only to consign the product to oblivion upon further review. Unusual only in the extent to which it has happened.

Jay,

Cezanne’s landscapes are glorious. They are for ..living with. A naive question, considering your list above, where do you personally draw the line with respect to these pieces are for looking.. or living with ?

Birgit:

I could make a wise crack about “anything beyond Pop Art”. But Albers was considered in that fold and I have seen many mannerly works done by these people. But some of it screams so loudly that I can’t hear what it’s trying to say – if anything.

Birgit:

I decided at some point that, should a disaster befall the art museum, I would try to save the Cezannes first. The ones in question are very livable and reward any length of attention.

i think as the creator of the work and one who has been looking at it for an extended period of time, your eyes get use to the work. Many artists advocate techniques like looking at your work through the mirror, leaving and coming back in 30 minutes, flipping the image, etc to give them a fresh look, mistakes that eluded you before are seen with clarity with fresh eyes