Under the catchwords of accessibility and inclusiveness, a lot of artifacts in the art world are losing its original meaning and interpretations thereof. Simply put: We inhabit a culture of simplification and generalization with the hopes that unpretentious agendas would be understood and assimilated by a larger audience. This has been documented extensively in other fields and is now seen to be creeping into the arts as well. Two examples from either sides of the Atlantic would further illustrate my point.

The Detroit Institute of Arts is getting a $158.2 million makeover in the hopes of recapturing the imagination of metro Detroit. The museum closed for six months starting May 07, plans to add 30% more gallery space, freshen facades, replace antiquated climate protection, add amenities, and untangle the mazelike floor plan.

The reinstallation promises to vividly alter how everyday visitors experience the museum, transforming the DIA into a populist hub for culture that strokes the masses without, the museum hopes, offending connoisseurs. The museum is reinstalling and reinterpreting 5,000 objects, rewriting thousands of labels in plain English, creating 11 high-tech interactive displays and videos, hanging large explanatory panels and adding kid-friendly features.

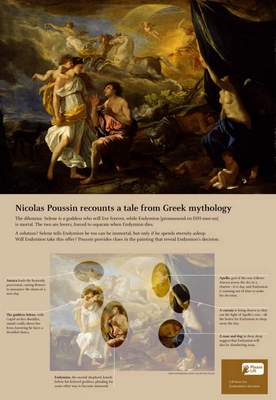

One of the most telling examples is a gallery devoted to eight paintings by 17th-Century Flemish master Peter Paul Rubens. “How can you identify a painting by Peter Paul Rubens?” asks a large panel. It identifies stylistic calling cards such as sturdy women with the glow of health and stories enhanced by dramatically arranged figures and expressions — but it never identifies Rubens as a baroque painter. A gallery exploring the fundamentals of modernism includes projected phrases above the art.

Graham Beal, director of The Detroit Institute of Arts, stands at the start of the Grand Tour of Italy gallery currently under construction (source: Detroit Free Press)

Special interpretive element such as a closer-look panel or flip label designed to bring viewers closer to the art (source: Detroit Free Press)

Next we consider the case of Tate Modern in London.

In May 07, Tate, in association with Creative Partnerships, BT and Channel 4 Television, launched one of the most extensive consultations ever organized with young people across Britain on plans for the Tate’s future.

150 young people from across England were invited to Tate Modern to take part in a day of workshops, which explored different options for the new development of the Tate building, its structure and to simplify the organization of its artworks. The teens were invited for a sleepover at the Tate where they slept in tents in a large hall called the Turbine Hall. Before they were allowed to turn in for the night, the teenagers had to decorate their tents with inspired designs. Inspiration ranged from pop art to Jackson Pollock. Others worked in groups to create small communes.

In autumn 2008, Tate will stage the first ‘From My Space’ to ‘Your Space’ Conference which is planned to take place simultaneously in all four Tate galleries. This will be organized by young people themselves and adults will only be able to attend by invitation. The Tate is also inviting young people to influence its future by designing a “creative manifesto” for Britain in the 21st Century.

Teenagers at the Tate working on their tents (source: CCTV.com)

Some catchy artwork on the tents inside Tate (source: CCTV.com)

While in the first case, simplification of art might make it a little more approachable to the common person and in the second it is commendable that teenagers are given more power, it is indeed a sign of the times that ‘arts’ and all that goes with the word is being progressively over simplified to the point of this being just another marketing or advertising exercise with lesser regard to a truer understanding of arts. Sometimes just taking the mystery out of art stops the viewer from thinking any further resulting in banal messages that are starting to get passed down from our generation to our children. Do you feel the same with respect to the arts in general or is it just my ‘cry wolf’ mind feebly entertaining its trivial pursuits?

In passing, I wanted to point out that Tom Meacham is showing with Oliver Kamm/5BE Gallery in Chelsea in a show called ‘The Greater Good’. He has decided to take the oil out of painting. He prints on the canvas using an ink jet printer.

Tom Meacham, Untitled, 2007, InkJet on Canvas, 57 X 38 inches (source: Oliver Kamm website)

Sunil,

Amazing how money is misspent in the art world. If they gave us $100,000 on A&P to allow us to turn our discussion into art in a more active way, we could change art history.

Maybe we should ask…

Regarding the relative sizes post, very interesting issues. I’m coding up a tool to allow me to show my pictures in any configuration I want to in web pages. The question of whether I should so the pictures in some abstract standard scale, or with realistic relative sizes is interesting and I’ll explore that now.

P.S., congratulations once again!

I read a good article along these lines somewhere else recently, but haven’t been able to locate it. It was in reaction to a show at the Tate Modern. Anyway, I’m conflicted about the trends you point out. I think it is important to involve audiences that wouldn’t otherwise ever visit a museum, if for no other reason than the need to justify public funding. The problem is how to simultaneously cater to more “sophisticated” audiences. This challenge calls for real creativity from museum curators and directors (which reminds me of Karl’s post suggesting we consider gallerists as artists — to me it’s different, but definitely creative).

Sunil, I didn’t get whether there’s any connection between your post topic and Meacham’s exhibit. He’s using a more democratic technique, perhaps. But I’m wondering if this should be a separate post. At any rate, there’s no reason to limit yourself to one a week, and also no need to make every post be a weighty one.

About that $100,000, I’m quite serious.

Here’s how I would propose spending the money. We have a lot of great discussions here, no lack of concepts with our group. Once a month we could decide which is the most interesting thread of discussion (not the same as selecting a given post, mind) and then we could discuss an art project to implement the idea. Then we would take proposals from people interested in doing the project, then we commission the project, for real money. Here is the “experiment” part of the cycle. When the project is done, and the artist paid, we discuss the result and propose a new project. Here we have the complete x-y cycle we discussed the other day. Not science, but art done in a serious way with practical economic support.

If they gave us $100,000 on A&P to allow us to turn our discussion into art in a more active way, we could change art history.

I have my doubts. But if anyone offers us the money we shouldn’t turn it down :)

David,

Not enough money, or are we not up to the challenge?

Anyway, did you read comment #4?

I guess it depends on who museums are for and how we expect people to engage with them. I’m sorry, but museums are traditionally very elitist institutions in which we are supposed to whisper reverently and bow to the genius we find inside. It is one insitituion that can afford to examine itself as to how to be more accessible to the “unwashed masses.” Even if some of these alternative methods seem more interesting and effective than others, I see more positives than negatives in making art more accessible. Can’t the sophisticates ignore all the extra text and guides and enjoy the art just the same? I love the tent idea with the kids actually. One thing that is so off putting about museums is that it can be so removed from the process of making the art. For kids especially, the more connections to the process of creating art, the better. They will be much more interested in looking if they have a clue as to how they are made and what the creative process actually feels like.

And call me one of the uneducated masses, but I often enjoy the annotated “guides” to paintings. Getting the details of the narrative of the myth that the painting depicts only adds to my enjoyment. And I don’t carry all that info in my head.

When I take my nursing students around the art museum as part of their art appreciation class, they are really into it. We talk about all of it, from the basics of what things are made of, to the formal elements, to the potential meaning of the piece. One of them actually asked me if the paintings are “real,” in other words she thought they kept the originals stored away and we were looking at copies!! Without that breaking down of information they wouldn’t have a way in. I truly think they will return to the museum now and look again and give art some thought. And I believe it will make them better nurses and more well rounded citizens. Did I “dumb down” or simplify the material for them? Maybe, but that allowed them to dig deeper.

Karl,

We are contributing to art – there is no question about it. If you page back and see some of the superb posts that some of the contributors on this group have put up, I think we have material for a whole book on art and its perception.

On comment #4, I see some potential. In fact the project that comes out of the discussion would be better received by the ‘public’ as they have ‘reference discussions’ to fall back on which gives the art/project more meaning. I think it is a good idea. Want to start off with a pilot?

I would be interested in taking a test drive of the application that you are building that will allow the relative size to be displayed for a given painting. I would be very interested.

Thank you for the wishes.

Not enough money, or are we not up to the challenge?

Neither issue. I just think we’re kidding ourselves if we think that anyone, given any sum of money, is going to change art history. Artists, sometimes very ambitious ones, do what they do. Art history is what it is. I have my doubts about anyone’s ability, regardless of talent or resources, to simply decide they are going to change art history and then do so.

Anyway, did you read comment #4?

I think I was writing comment #5 while you were writing comment #4 :)

Wow, and while I was responding to comment #6, Leslie and Sunil put in #7 and #8. It’s hard to stay current! :)

Steve,

I too am conflicted. On the one hand I would like to see kids interact more with museums and learn more about art/culture and exhibits being explained better while on the other hand, I feel that hand-holding and over simplification is the norm now and with more hand-holding comes the decline in critical thought and independent insight (have you seen the way children reach for their calculators on being asked to add a couple of numbers). I think a fine balance between the two would be the best bet, but it a difficult one.

I am not an art critic and by no means should I criticize others works but I could not help display Meacham’s work here as I feel that the work is symptomatic of the attitude outlined in this post. When you produce banal computer generated patterns and use an inkjet printer to lay it out on canvas, it again becomes emblematic of our current state (maybe I am being a bit too harsh here, but I could not resist putting up this as an example).

It strikes me that the kinds of supplementary materials described above for the DIA are more prevalent in anthropological and natural history museums. Traditionally, such institutions have focused more on education than on promoting aesthetic wonderment. Recently, it seems that such goals are being aimed for (successfully or not) via flashier and flashier means. But I would try to separate the issue of supplementary material from that of dumbing down, although the two appear connected.

Leslie,

You do bring about a valid viewpoint and like I was mentioning to Steve earlier I do not know the right answer. I am reacting to what I see around me.

The average kid today does not seem to have the mental dexterity that an average kid had 25 years ago.

Arthur,

Exactly my point,… Of course, I debate with myself hard on the separation between supplementary materials and the larger issue of oversimplification, but they do appear to be very connected in the larger picture… It seemed too ‘corporatey’ for me and you bought out a good analogy when you mention natural history museums…

Sunil,

“The average kid today does not seem to have the mental dexterity that an average kid had 25 years ago.”

I hear you and lament that a lot with my students. What I don’t know is how to test my reality about whether kids are really declining in mental acuity. Somehow I feel really old just now. Aaah, kids today :)

Arthur’s point about separating supplementary materials from dumbing down is a good one. Supplementing does not have to be spoon feeding. I would also argue that accessibility and inclusivity are not just catchwords. They represent true gaps in museum culture.

Sunil:

Speaking of threads, we’ve got some raveling going on – or weaving maybe.

Allow me to babble. As you may have surmised, I once worked for the Cleveland Museum of Art as an educator. MFA in hand, I marched off to find a nice collegiate teaching position and, instead, wound up at the CMA. I found there an upstairs-downstairs kind of society with the lower quarters occupied by the likes of me and the upper levels presided over by a kind of raj consisting of those who could afford to throw their paychecks in a drawer. Actually, the education department was fairly well regarded, thanks to the generosity of certain early populist benefactors. These folks had considered the nascent museum as a way to improve the education and skills of all those immigrants coming into the area. Direct communication with visitors was favored to the point where the simplest signs were eschewed in favor of a guard giving directions to the washroom. The education department interacted with one and all at a direct and verbal level, speaking with both garden clubs and kids from the ghetto. The education department also disappeared. Last seen it was tucked away somewhere in the basement, reduced and much changed. What happened from 1971 to now? One-on-one was progressively replaced by more impersonal communications, distance learning took the place of busing people in. Furthermore, the medium of art as spectacle was developed: the natural history museum has its animated dinosaurs and the CMA has its blockbuster shows. More money could be made hitching visitors up to walky-talkys and sending them off to the gift shop than staffing the shows with so many docents.

Do I approve of all this? Yes with some reservations. Not so many friendly faces to greet the kids, but I would wager that the CMA is now more like it’s founders’ original vision than it had been for a long time. Please remember that early plans for the CMA called for kitschy theme buildings to house the various collections: pagodas,little pseudo cathedrals etc. so Detroit may be getting populist, but it, like Cleveland has to face a world of lowered pedestals and heightened expectations from city hall.

Steve:

All things are possible, right? Let’s say I’m looking at a given work in the museum. I turn on my I-pod -style personal electronic assistant. It picks up my position and direction in which I’m facing. It then identifies the work in question and offers me a menu of options. I can hear some elementary patter or tune into something more complex and insightful. It can also direct me to other resources and tell me where to buy the mug and the t-shirt. Connoisseurs don’t have too much reason to grumble and a good time is had by all.

Designer labels roll out new fashions and fashion statements and the lay genuflect to the latest glitz.

High end galleries (and upscale museums) dress up and parade the artist of the day ensuring that prices for works remain inflated while demand and supply are controlled.

Yes, I believe you in your observations about the CMA (both positive and negative).

“…taking the mystery out of art stops the viewer from thinking any further resulting in banal messages…”

I’m not sure I get how explaining or detailing artworks leads to less thinking. I would think just the opposite would be the case. Take a look at the majority of art visitors and watch how quickly they move through the galleries. Most see little more than a pretty picture, then move along to the next. At least these explanations would give the layperson a foundation, however low, upon which to better appreciate the works.

As well, every BFA and MFA student has art history textbooks with similar detailed explanations of major artworks. Are they, then, being dumbed down simply by being educated?

A quick throw-in: call me lazy since I haven’t absorbed all of the comments. But a Mr. Kimmerle speaks wisely to the “banal messages” comment. A good work of art isn’t that fragile. One can mess it up with poor presentation, but even then layers of meaning are waiting,like fine cake in the fridge. Load up. The more the history, the more the mystery I say.

Sunil,

I don’t know the Detroit Museum, so I can’t speak directly to their exhibiting procedures. But the information in the review didn’t seem to point to dummying down (although clearly the reviewer disapproved) so much as to a change in direction.

It sounds to me like the museum may have changed from an historical to a formalist approach. Instead of being given the conventional set of dates and a label like Baroque, the viewer is given information about how the particular art work achieves its effects. This strikes me as a legitimate label and very useful to much of the world.

I have lots of friends who are thoughtful, learned, competent humanists and writers, but who are not necessarily educated much in the visual arts. And believe me, a formalist approach is what they can use when they look at art. What they don’t need is a label to set them off track, thinking about Milton and the ways of God and Man during the (British literary) Baroque.

So while we artists might see those labels as a dummying down, the rest of the world, even the more educated members of it, might be being educated up.

And as Leslie said so eloquently, having some hands-on information about the difficulty of making art is bound to make it more vital and alive to the viewer than if it’s all just theoretical.

So I’m with Leslie and Jay on this topic — I rather more approve of these current approaches than disapprove of them.

Although — I wouldn’t mind having at least one day dedicated to reverent silence and erudite labels, preferably discreetly displayed in large type (my eyes aren’t what they used to be) where I was the only one allowed in the museum. It’s a fact that the hoi-polloi will crowd around the good art and make it difficult for me to keep it to myself…… <snort>

Karl,

I like your $100,000 idea. Where do I sign up?

And I hope you are planning on doing a post about your thinking about sizing of images. I have casually started doing that on southeastmain, but not in a very methodical way. I do just enough manipulating of the respective sizes of the images to allow the reader/viewer to have some sense of the differences between, say a 12 x 16 and a 30 x 40 canvas. I regret that my website doesn’t do this.

I have to say that I’m skeptical attempts to make art museums more “user-friendly”. For better or for worse, museums seem inherently elitist to me. Many (perhaps most) of the objects in a typical museum were made under cultural assumptions foreign to the typical visitor (a risky stereotype, yes). This is true of classical statuary and it is true of contemporary avant-garde work. Explaining the context via simplistic, cliched wall-text isn’t enough, and may provide a false sense of security. This isn’t to say that “civilians” can’t or shouldn’t try to grasp museum art, just to say that the process is hard (as it is for anybody, at first).

To clarify, I am by no means against wall labels, tours and other supplements. But it is important, I think, to be modest (and skeptical) about their role as educational and popularizing tools. Aside from bare facts, what you’re getting is (in my experience, at least) typically a rote, simplistic point of view. Shying away from big scary words like “Baroque” isn’t the answer. Neither are audio and video and computers–these things are bound to be more popular than the works of art they’re obsensibly there to explain.

If wall text and audio guides provide an entry point for people to begin looking at and thinking about art, then that’s great. The problem, I believe, is that they also encourage people to look at the artwork as simply illustrations for the text.

Arthur, David, Sunil,

I agree that modesty and skepticism about public (or private) institutions are always useful. And certainly text can get in the way of the art. But I’m resistant to blanket condemnations.

If museums are to cater to a wide variety of people,and clearly they should be, and to people educated in a wide variety of ways, and to people with a wide range of experiences, they (museums) will necessarily have to use a wide variety of different tools. What works for one person, who may need to resist reading the labels, won’t work for another, who really wants to know the precise date that this Cezanne was painted.

And I think we need to sort through which tools might result in dummying down and which are wonderful additions. Once the audio materials got standardized and working reliably, I was very grateful for them. I could listen or not, I could look without having to peer at labels (which are always too small for my poor eyesight), and while I often don’t use the audio materials, I can see that others do and that the materials really work for them. They actually slow down the viewers, who look for what is being discussed in the audio. This can’t be bad (and if it’s annoying, the audio can be resisted). I think a wireless pointing system could be even better if it could be made to work.

Projected phrases above the art make more sense then tiny labels or painted information. Why not project them — cheaper than printing, I should think. And again, the labels can be ignored.

So I think before I’m willing to accept a blanket condemnation such as was presented here, I need more specifics about what is being done and said. I don’t see the use of audio equipment a dummying device, unless the recorded information somehow diminishes the art. I don’t see why the Tate’s activities are bad, although I’m a bit old to be interested in them. And the computer-generated art may be simplistic, but so is much paint-generated art. Bad art abounds. As does good art and museum folks who are desperately trying to entice and educate as well as present.

Judging from the responses here it almost looks like the jury is still out on the use of stultifying devices that simplify the museum going process. Personally I am the kind that would prefer to go to a museum, enjoy a little bit of quiet and soak the artworks and then go back home and explore the art and the meaning behind the same to imbibe it a little better. Of course this is time consuming and not many people have the time (I do not have it myself, but my fascination gets the better of me at times). On the other hand people like June and David eloquently point out the use of devices like the audio and projected phrases that make it easier for on-the-run folks who use the museum to quickly gain their cultural cup of tea and then be off with the knowledge imbibed. I tend to see it more like enjoying a cup of coffee from one of the roadside vendors in NY (a little bit of flavor, but it serves the purpose) and enjoying a cup of coffee at Barnes and Noble with a couple of books by your side and a companion who talks when needed. Different takes for different people.

Of course it should also be said that projected phrases and natural history museum type callouts that describe paintings tends to produce a certain set of people who become ‘instant experts’ thinking that all there is to know is known by just reading the callouts under the painting. That said, I cannot think of any alternatives that will help quench the thirst of the general public who need their quick culture shots.

Sunil:

I must take some exception. I might not be a bona fide expert if I were to absorb and regurgitate all the information on wall labels, but I would be a prodigy of memorization and would know more than most of the people working at the museum.

I don’t tend to think that the work/label axis is so terribly important. Viewers head for the text when they see something that attracts them. It matters that the information they receive is factual, leads them to further sources and is relatively free of adjectives. And it should never come across as the last word.

to me the key has always been the effect of aching feet. I remember walking by an entire gallery of Rembrandts at the Met because my feet were killing me.

Sunil, what you’ve posted here, in particular the information on the DIA, is a big reason why I have not pursued any more degrees in the art history/museum studies area because I can’t tolerate the dumbing down of museums’ collections or the constant ploys to make money so that a gift shop is more important than the art exhibit; Or worse, exhibits like gowns worn by Princess Diana or an automobile in the main lobby are put out to the public as fine art when they are really ways to pull in crowds and make money. (Just two examples from local museums)

I tend to ignore wall text in museums, mainly because I don’t want to die of a stroke. I see so many mistakes it drives me crazy, not to mention the patronizing tone so many have without ever passing along pertinent information. I believe wall text can be informative and interesting without alienating anyone.

Museums are increasingly geared towards children and the people that teach these children are ruining so much of what’s important about art and the teaching of it by behaving as if all children are so stupid they could never understand even the most basic formalistic ideas. Unfortunately, this “child proofing” of art extends to adults, too.

OK, I could write a book on all of this and I’m having trouble streamlining my thoughts because it’s important to me.

I guess the bottom line is, yes art should be for everyone but that implies that people have to meet art halfway at least and not expect it all to be handed to them in a safe, bland manner.