David Lewis-Williams in The Mind in the Cave and Inside the Neolithic Mind postulates that religion has its origins in hard-wired brain functions he calls “states of altered consciousness.” Among these altered states are the hypnogogic (just prior to and awakening from sleep) as well as states induced by consciously chosen activities, for example, rhythmic dancing, meditation, and persistent highly rhythmical sound patterns. And then there are the other well-known states, whether chosen or inflicted, that alter consciousness — ingestion of psychotropic substances, intense concentration, fatigue, hunger, sensory deprivation, extreme pain, migraine, temporal lobe epilepsy, hyperventilation, electrical stimulation, near-death experiences, and schizophrenia and other pathological conditions (Inside the Neolithic Mind, page 46).

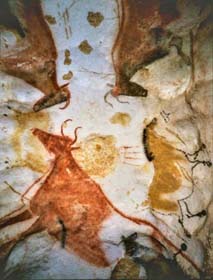

These states of consciousness, combined with homo sapiens’ ability to remember the visions that occur in such states, says Lewis-Williams, account for the rise of religion, some social organizations (primarily religious hierarchies), and the early paintings and art found in western Europe at places like the caves of Lascaux well as in the Near East around the upper reaches of the Tigris-Euphrates, Jordan, and Turkey.

The Mind in the Cave has as its sub-title, Consciousness and the Origin of Art, and while I’m not equipped to evaluate either the neurology nor Lewis-Williams’ archaeological arguments, what he describes as a hard-wired state of the human brain which leads to art (my words) seems valid to me.

It has long been part understood that altered consciousness evokes visions that are used to make art. Think of Coleridge’s Kubla Khan (“A damsel with a dulcimer/ In a vision once I saw”), reportedly a result of an opium dream. Or Wordsworth’s “sense sublime” in Tintern Abbey whose “affections gently lead us on,/ Until the breath of this corporeal frame/ And even the motion of our human blood/ Almost suspended, we are laid asleep/ In body, and become a living soul:/ While with an eye made quiet by the power/Of harmony, and the deep power of joy,/ We see into the life of things.”

What occurs to me (and granted it’s a pretty old thought, dressed up by recent neurological research) is that artists, like masters of meditation, are able to achieve an altered state readily, without “artificial” stimuli or illness. They seem to be able to achieve these states more easily than others in our rational, conscious-brain-oriented society. On A&P we talk about being “in the zone” or not noticing the passage of time while we are working. We see things differently because we’re talking and looking at art, as Birgit did on her walk after Steve’s post on quotes from O’Keefe. Sunil talked of living the life of art. I noticed that sometimes I see differently when I’m casually photographing.

We use specific activities or objects as triggers to that altered state, which might be why Karl and I are neither self-indulgent nor masochistic when we work outside. We can obtain some condition of mind that is conducive to our art work; we find our “sense sublime.”

It’s this old knowledge, now validated by science, which provides not only a reason homo sapiens are religiously inclined, but, more important to this group, that art might be a specific function of those altered states. With that knowledge, it’s possible to gain credibility for the importance of artmaking to the whole of civilization. Lewis-Williams says that the earliest “artists,” particularly those who depicted clay figures and skulls with predominant eyes (I keep thinking of Emerson’s “Transparent Eyeball”), were not among the elite shamans and high priests of an organized religion, but rather ordinary people expressing what they saw in their day dreams or fatigue or hunger.

Lewis-Williams isn’t sure he approves of such states of altered consciousness, even though he says they have produced Bach, John Donne, Shakespeare, and other great artists. He says: “The exaltation that those great creators excite in us does not justify mystical atavism. Shamanism and visions of a bizarre spirit realm may have worked in hunter-gatherer communities and even have produced great art; it does not follow that they will work in the present-day world or that we should today believe in personal spirit guides and subterranean worlds. We can catch our breath when we walk into the Hall of the Bulls without wishing to recapture and submit to the religious beliefs and regimen that produced them.” (p 291, The Mind in the Cave)

I guess my question for the day is, am I out in la-la land, imagining that we might ally our rational brains with our (irrational) altered consciousnesses (without necessarily adding any specific religion to the mix) and in doing so enhance our abilities to produce art? And might this become not be only broadly acceptable, but a democratizing of the artistic impulse, rendering it more accessible to everyone? In some ways the DIY movement, the democratizing of art, could be seen as a way into this understanding, giving people a greater knowledge of the mental state out of which “visions” arise. Lewis-Williams says that the earliest altered consciousnesses that we have physical evidence of are the most “democratic,” non-hierarchical. This seems to fit into a DIY world, where it isn’t just the artistic elite among us who can vision and produce art.

I also might venture to ask if this alliance might not actually be a necessary piece of the human condition, and if it were to become part of our greater knowledge,we might make greater intentional use of it. We might move away from sectarian religious upheavals without losing the sense and usefulness of what sometimes is called spirituality. The irrational can be understood as hard-wired into us and turned to good ends, without falling into superstition or la-la land.

And as a side-note, which may or may not illuminate — I have been wont to say that theories of Gaia are really just sentimental foolishnesses, and that Ma Earth will get along quite fine without homo sapiens. She really doesn’t care what we do to her — she’ll just keep rolling along. On the other hand, in my irrational states of altered consciousness, I’m a Cenozoic patriot, and even though I rationally know that in the long run of geological history, what we do doesn’t much matter much at all, my irrational mind insists that the rational information doesn’t much matter. Something outside my rational mind insists that I care for the environment, even if the environment doesn’t give a damn. Not a bad use of an vision from an altered consciousness.

Jay,

I am returning the compliment. You are too modest too.

Why not expand on something said earlier? It adds more depth.

I don’t know a lot about physics and quantum mechanics. The most I can say is I’m a huge fan of the movie What The Bleep Do We Know. But, I encourage anyone to Google Buddhism and Quantum Physics, you might be surprised at what you find.

Birgit, I think it’s great that you could do Reiki; it’s become rather popular these days. I haven’t learned that myself but I know about possessing healing energy. I would argue with you about it being mystical. I think it’s something all humans possess and can access it with some effort on their part. I think this energy is simply part of being human.

Birgit:

Happy to oblige. But could you expand upon your request for expansion?

All of us, mostly, are modern humans, versed in language skills and accustomed to expressing ourselves with a rich variety of words. I use words myself, though clumsily, and as I’ve pondered the comments here, I’ve been re-examining (as best I can) the connection between words and actions. I will try to outline my reasoning for why I think words typically follow actions, how this order reveals the workings of our brains, and ultimately, with that understanding in place, suggest where it might be fruitful to look for creative inspiration (which is the reason I think June was interested in altered states).

It seems the example of throwing a stone (that I borrowed from William Calvin) is thought to be too complex by some to occur without language. Calvin’s idea actually suggests that the naturally selected physical attributes that allowed hominids to increase the distance and accuracy of stone throwing included the mental machinery for sequential thought (bigger brains) which accidentally provided fertile grounds for the development of language.

Calvin’s theory appears far fetched to many of us because it paints language, one of our crowning human achievements, as a lucky by-product. But Calvin’s theory addresses a puzzle written into our best archeological and fossil evidence. His theory seeks to explain why some 2.5 million years ago, hominids were happily chipping away at and using stone tools but not really speaking about it or showing uniquely human characteristics until approximately 40,000 years ago,

Tree claims that the sequence of words I used to describe the act of throwing a stone is evidence that stone throwing relies on words. I think that Tree makes an error here in equating a description of an action with the action itself. But try as I might, there doesn’t seem to be a way for me to divorce my words from my descriptions (or actions?).

In our culture of words and books and television, even when we learn an action for the first time, it is usually to the accompaniment of a steady stream of words and instructions from an experienced relative, teacher or coach. For us, raised in a culture that uses language, words are necessarily linked to our actions. Even so, it is not clear to me that our actions are dependent on our words, or even on our thoughts. As hard as it is for us to imagine throwing a stone without language, poop-throwing, tool-using monkeys demonstrate that it can be done. Learning need not be accomplished through language. Effective learning strategies need be no more complex than monkey see, monkey do. It is important to consider examples of learned behaviors in our fellow mammals precisely because they do not seem to utilize language. It is proof of concept – action without words.

Young squirrels learn how to chew open nuts and become more and more efficient at doing so. Presumably, they remember where they hide nuts.

Beavers, as I mentioned before, cut down trees, harvest the bark for food, store it for winter, parcel out the wood for construction tasks, build mud insulated wooden huts, engineer dams, canals, and alter the environment to favor their survival.

Apes recognize themselves in mirrors, practice deceptive behaviors, form social alliances for political reasons, fish for termites with sticks, use rocks as hammers and form hunting parties to track down monkeys with the intent to kill.

All of this is accomplished without language as we know it, and if we argue that it is accomplished with language, then it seems to me we become obligated to grant all primates inalienable human rights.

I took Tree’s plain assertion (that words must be the catalyst for action) seriously and spent some time trying to monitor the mental process I use when I undertake simple or complex tasks. My experience is that, even if I try to ‘think what I’m doing’ – turn the key, open the door, sit in the seat, crank the ignition… my commentary or narrative are soon overwhelmed. I can’t keep up. In fact, it seems I don’t even try to keep up. Usually what happens is I start to think about other things. Say I’m driving to work and I see a lady running to catch the bus, but she is too far away and the bus is already leaving. As I drive past the desperately running lady, I see her unexpected physical exertion reflected in her face. I see and empathize with her evident dismay. It looks like it was important for her not to miss the bus. She’s really dressed up. Maybe she was headed for a job interview. Maybe I should help. Maybe she would be afraid of me. I wonder if perhaps I might not be missing my own metaphorical bus by not more actively pursuing my own job interviews etc. Before I know it, I’m at work. It is sometimes troubling to realize that I don’t really know who is responsible for driving me there (But more often then not he does a good job).

It seems that at least a part of me is fully capable of working not only without words, but maybe even without consciousness.

I am aware from my readings that the brain has many different structures in it. I think there is a primitive brain stem that handles most of the things that reptiles need to do to be able to function. I know there are two main hemispheres that are slightly asymmetrical, that have unique properties, that are hooked together and that communicate – but one is dominant. I know there are various lobes here and there associated with particular functions. But I guess the point is, wherever in the brain our word-befuddled consciousness may reside, it doesn’t seem to be the boss.

Think of the brain as composed of Capt. Kirk and Dr. McCoy – Action and Emotion. Then at the end of the ice age, add a Mr. Spock Module that has thought and logic and language. Clearly, Mr. Spock is an important addition to the federation, but Capt. Kirks instincts and reflexes coupled with McCoy’s emotions frequently trump Mr. Spock’s advanced thinking skills.

O.K. That was a really crappy analogy.

Anyway, if we view thought and language as recent developments, we can see signs that they haven’t been fully integrated into our makeup. We all know that smoking is harmful to our health, but a significant portion of us insist on continuing to smoke. Overpopulation seems to be a problem, but couples often insist on having big families. We have the capability to be rational, so it seems, but we are seldom rational.

I wonder if the desire to experience altered states isn’t the Mr. Spock module rebelling against the responsibility that his reason imposes. With reason, we can begin to predict the near future and plan accordingly and this is harder than the good old days when we could just go throw a rock at an animal and eat it for dinner.

Maybe we glamorize those raw feelings and inbred instincts as being closer to nature and more about what it is to be human than we should, because the real altered state is this new experiment in consciousness that has never been tried before and by which we distinguish ourselves from the other animals.

Scott:

You know, from what I have gathered here, there is no such thing as an altered state, as all the states seem to eye each other suspiciously. I guess, for me, an unaltered ground state is the one that best serves a given set of survival requirements. Furthermore, I would assert the mind’s right to exercise more than one state of consciousness at a time. On your drive to work, you may have admired the distressed woman’s ensemble and had an aesthetic reaction to a poster on the retreating bus, and not missed a beat in your driving. My assertion here might be that the judgemental/ruminative is coexisting with the reactional/actionative.

And, if I can remember a far-off course that I once took, the monkey’s ability to learn how to throw fecal matter is referred to as “monkey see – monkey doo”.

Not only can nobody describe a Greg Louganis dive accurately in words, I can’t even imagine it being described in anything approaching the accuracy required to execute it.

Hi Scott, no error on my part. I wasn’t confusing description of an action with the action itself. I suppose I still stick by my original argument about humans, language and actions. I think it would be enlightening to read about “feral children” who were raised without being taught language. That may help me understand this subject better.

Steve:

In comment #43, that was a four “a” “way” eh?

Maybe it should only have been a three. I got carried a-way.

Steve:

The Eastern Mysticism thing had gotten you into mantra mode. It’s a testimony that you stopped where you did.