I’ve been following, if not commenting on, the discussions on blogs and their usefulness to a community of artists. And that led me to thinking about communities of artists.

All kinds of communities of artists have existed — ateliers of the Renaissance, –the academies of art — museum schools where students sat on the floor drawing ancient scuptures– the artists who rebelled against the academy in Paris– the Group of Seven took on Emily Carr in the late 1920’s — the New York School whose members drank together at bars, married, divorced, remarried each other– well you get the idea — art camps, colonies, ateliers, workshops, studio spaces, hanging with artists — all comprise community. And now we have the internet, adding another element to the possibility of community.

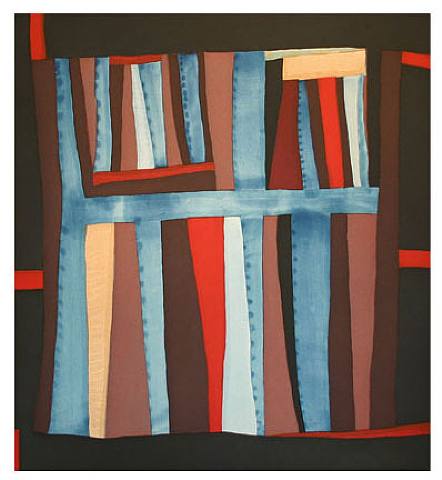

One of the most fascinating communities of artists is that of the black women of Gee’s Bend, Alabama, whose quilted art was exhibited in Houston and then at the Whitney in 2002. [Michael] Kimmelman in the New York Times November 29, 2002 regarded the exhibit as

“..Some of the most miraculous works of modern art America has produced. Imagine Matisse and Klee (if you think I’m wildly exaggerating, see the show) arising not from rarefied Europe, but from the caramel soil of the rural South in the form of women, descendants of slaves when Gee’s Bend was a plantation. These women, closely bound by family and custom (many Benders bear the slaveowner’s name, Pettway), spent their precious spare time — while not rearing children, chopping wood, hauling water and plowing fields — splicing scraps of old cloth to make robust objects of amazingly refined, eccentric abstract designs. The best of these designs, unusually minimalist and spare, are so eye-poppingly gorgeous that it’s hard to know how to begin to account for them. But then, good art can never be fully accounted for, just described.” (as quoted on the website of Shelly Zegart)

It would take a book (it has taken books!) to explore the elements of this isolated black culture, impinged upon only occasionally by outside elements and then left behind, abandoned to their own self-sufficient ways. The community is surrounded by a big bend on a river, and was part of the southern slavery and then sharecropper system (with absentee landowners) until the 1930’s. The Roosevelt years saw some federal programs going through the area in the 1930’s. They made loans that helped people be more independent of local white landowners, but that program was discontinued in the 1940’s. Martin Luther King appeared in the 60’s, and the Gee’s Bend people joined in the Civil Rights marches and attempts to vote. At the same time and in part because of the Civil Rights movement taking note of the community, the women of a nearby community, along with some of the Gee’s Bend women, were launched into a folk art business, selling textile work in high end New York establishments, turning out fairly banal home dec work designed by others, through a coop managed by a white woman. That fad passed and another period of isolation occurred, enhanced by the loss of the ferry that linked them to the only town nearby (Camden) — the ferry was stopped when King encouraged the people of Gee’s Bend to vote in the county elections. The Gee’s Bend quilts were “rediscovered” in the 1990’s, when the quilted art community had grown its own strong culture.

What is clear when you see exhibits of the Gee’s Bend art is that the isolation and community are part of amazing individual comprehensions of how to make visual beauty.

The Gee’s Bend women, according to William and Paul Arnett (in The Quilts of Gee’s Bend) were “steeped in strings and scraps –leading toward techniques of pure abstraction as the foundation of their talent and attitude.” The families of women were strong centers of action, and daughters were expected to learn to make quilts. Some learned to make art while making quilts.

This community evolved its art out of its necessity, proving (as if we needed proof) that the aesthetic is a fully human function. But two other things about the Gee’s Bend work occurs to me. One is that the isolation of this community and its poverty and need to make-do stretched its artists beyond what more fully integrated communities with more money have achieved in the same field. The other thing that delights me is that these are fully abstract artists, designing with all the boldness and clarity of vision that we find in the abstract expressionists, but without any input from the “modern” world. It is a confirmation that abstraction is an art form as closely tied to the human need for expression and aesthetic outlet as any religious icon or painting of a sunset.

A large number of images of the original exhibit can be found on the Gee’s Bend Quilt website.(The two images above are actually prints of more contemporary works from the community; the original exhibit used works primarily from the 50’s, 60’s, and 70’s). I would urge you to look at the scope of these art works, done originally as functional items of home comfort, made by women who lived near one another, knew each other intimately (one artist identifies quilt makers by the smell of the individual quilts), taught one another, passed on traditions and ideas about beauty. This art confirms my deepest held ideas about varieties of aesthetics contained within the human psyche. It also contributes further to our understanding of artistic communities.

A couple more notes for those interested: Richard Kalina, in Art in America, Oct 2003, has a long and glowing review of the art in the exhibit: He says “It is clear that Gee’s Bend quilters were neither insular visionaries pursuing idiosyncratic personal paths, nor were they simply the skilled passers-on of traditional forms. Instead, they were like other artists of their time, adept, committed practitioners engaged in a measured and ongoing esthetic give-and-take.”

Alicia Carroll, at an Auburn University symposium, says,

“Formed at the close of the twentieth century, the exhibit was curated during the epoch-making moment of violence in the new century’s America; it reached New York, a city both in recovery and in deep reflection and mourning over the events of September 11th 2001. The Whitney became a public space to grieve for private and public loss and to celebrate individual and communal American achievement. The exhibit’s rhetoric implements elegiac language to construct national longings and anxieties over both recovery and loss. Received as survivors, the tattered and faded quilts speak to an American future that is far less optimistic than ever before. As the show travels in its “national” tour from one American city to another, it enters the “circuit of culture” in which its production enters into its exhibition and consumption in a dizzying exchange of meanings. The quilts have become national icons; what words will we ascribe to their eloquent silences? And what stories will be displaced in their new narrative category as apocalyptic millennial art? What new contexts will they meet and, in short, what are the consequences of subsuming Alabama quilts into a narrative of American elegy?

Some interesting questions arise, however, when we think about the art of Gee’s Bend. Clearly some of the quilts are art; some are nice-looking functional work; some are not artistic at all. The exhibit curators culled out the best of the work, leaving lots of what was available un-exhibited. And, I am told that even some of the things exhibited lately in “The Architecture of…” exhibit isn’t really gallery-worthy.

But everyone, myself included, talks about the “Gee’s Bend quilts.” Not about a singular artist (although the quilted art pieces themselves are attributed to individual women who are credited with the art) or a singular work. Even the styles, within the “piece” format of the art, vary greatly. And yet, because the community is so strong (and because it has a mythical quality for the rest of the US) it’s “Gee’s Bend art” not Loretta Pettway’s or Mary Lee Bendolph’s work.

Is this a flaw in the way we are thinking about a body of work coming out of a single community? Or is the flaw in our own ego-centric, individualized idea of how art is created and what it is worth?

Great piece, June although I’m a bit confused at your question. If we refer to “the New York School,” the “Expressionists,” etc. then aren’t people implying that these women are part of art history by using the term Gee’s Bend art? You mention two quilters’ names in your piece, so the information on individuals exists and can be accessed by anyone who wants to learn about them.

I think that twenty years ago, even less, one never would have seen an exhibit of women’s quilts in a major museum. This is a huge step forward for women artists and art in general. Yay!

June:

Good post. These Gees Bend quilts can be quite impressive.

But these examples raise a question that you may be able to resolve for me. Michael Kimmelman talks about the impoverished and necessitous lives of the weavers, which resonates with my small experience in some rural pockets of the South. I believe that I am correct in stating that the patchwork quilt began as a form of recycling daily fabrics, with a little store-bought thrown in. The traditional result has been just that, a more or less artful patching together of scraps and useful sections. But many, if not most, of the Gees Bend quilts don’t conform to that. We see instead, broad expanses of seemingly pristine fabric of a single type and color, which don’t square with any impoverished lifestyle that I know of. Can you direct me to a source that would allow me to see the context in which these pieces are and were made?

Please pardon the small note of skepticism that crept into my comments, I’d love to believe the narrative that features a small and isolated community of quilters in a backwoods creating world class work. But I hear tales of native and “naive” artists being managed and guided by advisers and managers with the goal of market penetration.

Tree —

One of the first exhibits of quilts as art was an “op art” exhibit somewhere in the east (can’t remember, too lazy to look) in the late 1960’s. And in 1972 the Whitney had an exhibit “Abstract Design in American Quilts” that got rave reviews. So it’s been a few more than 20 years that quilted art has been storming (or attempting to smother) the art world.

Jay–

The Gee’s Bend website is probably a good place to start, but if you google “Gee’s Bend” you’ll find lots of other materials. I have two books: “The Quilts of Gee’s Bend” and “Gee’s Bend: the Women and Their Quilts” which have a lot of history and photographs. These books are expensive, but you might be able to find them in a library. And as I said, the web is full of information. Wikipedia is a good source to start with: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gee's_Bend,_Alabama

I understand your skepticism. I can’t vouch for the images I’ve shown you (most of the images of the work is heavily copyrighted and I didn’t feel I could use them) — those that are prints of the originals are recent work and thus the fabric in them are more likely to be new than recycled.

However, I can assure you that I saw some of the art in Portland, and it was definitely recycled materials, laid on in these big beautiful sophisticated swatches. However the images on the web look, these women really were poorer than we can imagine and more isolated. Some of the fabrics came from the 70’s when they were part of that coop that did pillows for department stores — Sears donated a batch of corderoy that they used to particular advantage. And there’s an African print, also donated, that got incorporated into at least one piece.

But the coop work was a fad among the buyers and disappeared rather quickly.

One reason that the Gee’s Bend work doesn’t look like ordinary recyled patchwork from middle America is their isolation. They didn’t have the advice of the county agents in Ohio and Indiana who taught quilters about quarter inch seams and tiny stitches etc.

The peculiar isolation is partly a trick of geography. Gee’s Bend lies in a big balloon of land almost surrounded by the river. The nearest town is Camden, but it’s on the other side. When MLK set up marches for voting rights, the Camden government closed down the ferry to prevent easy access to their town from Gee’s Bend. It only reopened in the late 90’s after the Gee’s Bend quilts became a national item.

The women aren’t naive in any general sense — and having gotten some help from the feds during the depression they have been less susceptible to pressure from landholders (which is why they could join the Civil Rights Marches). But they are definitely not culturally middle-America nor did they have any conventional art in their lives.

I saw four of the women at a talk in Portland; each of them spoke in turn. The talks were amazing — more testimonials from church than anything we would imagine being a way to address the public. And one woman, Mary Lee Bendolph, sang. She is 70 and I was expecting a wispy voice, but oh no — it was so powerful — a shape singing style — that it drew people in from the classrooms and spaces that lined the hall where the talk was taking place. One of the younger women was clearly of another generation and had moved away and gave a more or less standard speech, and Matt Arnett, one of the primary collectors of the art, was the interlocutor, explaining to us what was being said (rather unnecessarily, I though). But the three who stayed closest to home were, for me, totally exotic.

So Jay, I do understand your skepticism. But these women had no exposure to art except through magazines and newspapers that might have come their way. Those would have been few and far between because of their isolation and poverty. The three times where their isolation was interrupted was when the feds sent a photographer and some lending agents to Gee’s Bend in the 30’s because it was such a striking example of abject poverty; the appearance of Martin Luther King in the 60’s; and the coop work in the early 70’s, which got them to a nearby neighborhood, where they joined others in the sewing. They were isolated in between and after these intrusions, until the Arnetts were directed to them by a survey of Kentucky quilts done in the late 80’s and 90’s. The art in the first exhibit in the 90’s was from the 50’s, 60’s, and 70’s.

By the way, in the 30’s there were also recordings made of the singing, which I haven’t heard yet, but want to get to. I can’t say this strongly enough — these women made this art totally outside any knowledge of or input by the modern art world.

An observation:

Yesterday, readers were presented with the work of an artist who includes in his paintings images lifted directly from mainstream news media, yet no one questioned the authenticity of his work. He depicts Joan of Arc going into battle completely nude while George Bush is fully clothed and again, no one questions why.

Today, we have a post about a group of women quilters and their works and right away, their authenticity and by extension, the integrity of the women who made them is put into question.

This angers me and the fact that the response to this was to present a detailed defense of the work saddens me because as far as I’m concerned it needs no defense, it stands on its own.

Hi Tree,

You are correct that the art needs no defense. I think the defense was that this is not a case of some city slicker teaching a bunch of backward women to sew things together, but rather a group of women who through their own culture and efforts have made art that rivals any in the same style and a lot of others besides.

Oddly enough, there is an artist who is working with a group of Bosnian women who has (although without the negative connotations) taken her training in art and applied it to cloth and then taught a group of refugees/displaced persons to sew the materials and make artistic decisions about the lines of quilting:

http://www.bosnaquilt.at/en/bq.htm

Tree:

Who knows why Jeffrey Isaacs calls his nude Joan of Arc. Ask him yourself.

As an art history major you must be aware of the appropriation of “folk” arts and crafts. From Irish clog dancing to Sepik River sculpture, one sees a pattern repeated in which a local artistic tradition will be bent out of its original shape by larger cultural and commercial interests. I appreciate June’s patient response to my query about this, and her assurances that the Gee Bend women haven’t been herded about.

As it is, we are all fighting our own personal race, gender and class battles. Me, I’ve made it a personal task to rid myself of any reflexive responses to the work of others based on such factors. There can be a point where negative attitudes actually reverse polarity and become positive. Empathy can end up feeling good. Braggin’? Hell no – just admittin’.

A further tidbit of gossip about the Gee’s Bend women — the gentlemen who “discovered” them (collectors of folk art) have been largely responsible for getting them so well known around the US. But they are now being sued by a couple of the women for “exploitation.” Some of the designs have been used to make rugs and other commercial products and some claims have been made that the reimbursement to the women was inadequate. The case is in the courts right now.

So maybe, Jay, my patience comes out of a cynicism about the way money and art work in this country. Didn’t someone note that they are equally worthless until declared to be officially worthwhile?

June,

As one much less knowledgeable about fabric art, I imagine the reason one talks about “Gee’s Bend quilts” is simply our state of familiarity with the art in general. I certainly would have had no association with Pettway or Bendolph. Just as I wouldn’t recognize Lismer or Macdonald, but I have some notion of the Group of Seven.

I am fascinated, like you, by the abstract expressions in these quilts. I especially like the second one you showed. But I have to say I like far better contemporary abstracts like Lisa Call’s work. I’m tempted to make a distinction between “sophisticated” and “primitive” abstraction, but that doesn’t seem quite right, not to mention sounding like a value judgement that I don’t mean at all. Some watercolors I saw last night that I really loved I would also call primitive (partial) abstraction. How do you think about this?

I am not sure that I understand about ‘folk art’. Perhaps it just means how close we are to a particular culture?

A couple of decades ago, some of my colleagues went to Zimbabwe where they collected Shona art. One even apprenticed himself to a Shona artist. I cannot remember the names of any artist but I do remember their spectacular artwork.

Perhaps, in a few hundred years, West European culture will be considered ‘folk art’.

Steve,

The difference between the Pettway/Bendolph art and Lisa Call’s art is like day and night. They both use textiles, but Lisa’s training has been as a professional artist; moreover, she is methodical in her choices and use of fabric, rather than having to use what is at hand or what she can trade for. She understands and can articulate elements and principles of design and talk knowledgeably about the art world; the GB women saw their first modern art on one of the tours after 2000. And, her art is far more complex and the surface far more entropic than that of the Pettway/Bendolphs. The art of the women from Gee’s Bend is reliant upon simplicity rather than complexity, upon colors which are meant to talk to one anther rather than set up a contemporary anthem of sound.

Hmm, I seem to have strayed into another field. Anyway, I like the Gee’s Bend (Pettway/Bendolph) pieces better than Lisa’s but that’s at the fine edge of personal taste. They are so different that it’s hard to compare them.

And I’m glad you pulled back from the word “primitive” — it’s a loaded term that probably can’t be used any more without people like myself going screaming into the night.

Birgit,

Like you, I am suspicious of the term “folk art.” One reason why I played with the names of the artists within the Gee’s Bend Collections is that it’s easier to talk about folk art when you have a tidy category — gee’s bend — than when you have individual artists whose work differs one from the other– Bendolph/Pettway.

I think “folk art” is art of The Other — women, oldsters, people from the country viewed by those in an urban environment, etc.

There are more careful delineations, of course (isolation, obsession, etc) but they generally begin with the notion that it’s art done by “The Other,” those not like ourselves, not having gone to University. There’s an element of patronage in the term and often in the treatment of the art and artist. I suspect this is what Tree reacted to in her earlier post about the art of Pettway/Bendolph/et al. Certainly the “folk” of Gee’s Bend differentiate the work of the various artists, knowing whose style was whose, who got ideas from her mother, who was working with a neighbor when she did a particular piece — the same kind of sense we have about Lisa Call’s work vis-a-vis June Underwood’s.

Jay, I see a big difference between the first paragraph of your comment and the last paragraph.

My comment was directed towards the first paragraph which I read as questioning whether or not the women were impoverished enough and authentic enough.

As for the nude Joan of Arc, my interest doesn’t lie so much in why she’s nude, my interest lies in why no one pointed it out. You mention my art history major, well I’m sure if a slide of this work was shown in a class, you can believe that wouldn’t go unnoticed.

As for appropriation, I’m not familiar with the Sepik River sculpture you mention, but I worked on an exhibit of art from Papua New Guinea and one thing that was crystal clear was the lack of art made by the women of PNG because they were/are not given the same opportunities as men.

I find it hard to believe anyone can rid themselves of reflexive responses; seems like a perfectly normal thing to do and can often save one quite a bit of time–and that doesn’t mean it’s the only response one has.

Also, many artists use their gender, class and/or race as a primary theme in their work. Where would someone like Kara Walker be today if not for the reflexive response to her work?

Anyway, I find it curious that you wrote this yet your original comment is definitely about class. Maybe it’s because one cannot discuss these quilts without class, and gender, being a part of the discussion? I think so, and I think that’s great.

Tree:

Let’s go over this some more. If you don’t care why the figure is nude, then why should anyone else? By the way, I would urge you to show that piece by Jeffrey Isaac if you are teaching a class at this point. I would really like to hear what the class has to say about it.

Ah, then you know from Sepik. Sepik River sculpture is ceremonial and relatively abundant as new work must be done for each ceremony – kind of like Navajo sand painting. It stems from and partakes of a tribal setting. As you are aware, the religious life of some tribes in this world is handled by the priestess and others by the priest. I think that to bemoan whatever is gender-specific in this work as an example of some form of male domination is to disrespect the culture from which it arises. And to raise this kind of issue is to leave unanswered the question of why there are no men represented in the Gee Bend group. Some plot to keep the men folk down?

Gender, race and class work if they provide a deepening context to an artist’s output. But to lean on these things as a prop is to ultimately weaken effectiveness over time.

You mention Kara Walker. If I remember, she does excellent cutouts. To think that she couldn’t achieve distinction without reference to her racial background does her a great disservice. Anyway, her references to racial issues tend to be highly nuanced.

Hi Jay,

It’s clear we are on completely different pages. I’m not sure I have the time or energy right now to go point by point through your last comment to try and make you understand what it is I’m saying, although I’m disappointed that you have missed my points entirely.

I choose to be amused at your comments regarding Sepik River sculpture and PNG culture and will leave it at that. It’s better than being angry. I’m sorry that we don’t live closer to one another as I’d be more than happy to show you the exhibit catalog and whatever else I still have from the PNG art exhibit. Maybe then you’d understand what I am saying here.

Kara Walker’s work is based entirely on her racial background, to say it’s highly nuanced is like saying Bill O’Reilly is a subtle commentator on world events.

I don’t teach art history as a profession. It seems to be a rather thankless task, no?

I will always disrespect male dominated, patriarchal societies and I will do so whole heartedly.

Hi Jay and Tree,

If I could present work as powerful as Kara Walker’s I would feel like my life’s work had been sustained.

June: as always, a very scholarly one.

I learned history…

“When MLK set up marches for voting rights, the Camden government closed down the ferry to prevent easy access to their town from Gee’s Bend”

Art helping community…

“reopened in the late 90’s after the Gee’s Bend quilts became a national item”

Self taught art

“art of the women from Gee’s Bend is reliant upon simplicity rather than complexity, upon colors which are meant to talk to one anther rather than set up a contemporary anthem of sound”

Art can mimic natural selection and evolution when left to itself… (think of the amazing diversity in the Galapagos)

“isolation and community are part of amazing individual comprehensions of how to make visual beauty”

Half hearted approaches towards emancipation and elements of opportunism

“loans that helped people be more independent of local white landowners, but that program was discontinued in the 1940’s” and

“coop managed by a white woman”

Great post… I liked the abstraction as well, but they proved to be a distraction when confronted with the heavy dose of social realism that some of these artworks are loaded with…

For an interesting perspective on Kara Walker’s please see http://lamgelinaoly.blogspot.com/2007/11/is-there-room-at-inn-for-kara-walker.html

Sunil:

Thanks for the link.

If one is looking for an artist who doesn’t make an issue of his racial identity, then I would suggest Martin Puryear.