I was fascinated by the research of an ophthalmologist that focused on visual infirmities plaguing artists in their later years and the effects of the infirmity on their art in Tuesday’s New York Times science section.

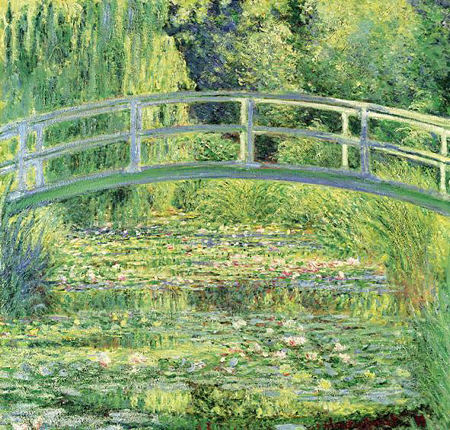

“On the fifth floor of the Museum of Modern Art, a three-canvas set of Monet’s water lilies spreads across a gallery wall in dazzling homage to the artist at the height of his brilliance. Off to one side is a painting of the Japanese bridge at Giverny from the early ’20s, when Monet’s cataracts were at their worst. It is a disturbing mix of dark reds and browns, much darker than the water lilies, yet just as compelling, perhaps, in its brooding intensity.”

“What has long been known about Monet’s later years is that he suffered from cataracts and that his eyesight worsened so much that he painted from memory. He acknowledged to an interviewer that he was “trusting solely to the labels on the tubes of paint and to the force of habit.”

Degas suffered macular degeneration, Renoir had rheumatoid arthritis, Mary Cassatt had cataracts and seizures attended to van Gogh. In almost all of these cases, the infirmities that attacked these famous artists happened after their places were assured in history as great artists.

This has led me to speculate that once an artist gains recognition, it does not really matter what that artist develops, we just look for and want confirmation of the fact that it was indeed painted by the person – be it illegible scrawls, colors incoherently massing into one other to form a dirty mess or just plain lack of attention to details (details that were earlier captured to meticulous effect) – it does not matter. We overlook incompetence (brought on by the onset of disease, drug overdose or otherwise) and reward the artist for what s(he) were once famous for…

Claude Monet, ‘Waterlily Pond’, 1899; Oil on canvas

Note: His vision problems did not start until 1912

Claude Monet, ‘The Japanese Bridge’, 1918; Oil on canvas

I just wrote a post at my site on Late Style, probably at the very same time you were posting this! Strange. I took sort of an opposite view–that a lot of older artist’s work is unfavorably compared to their younger output, whether legitimate or not. The weight of public expectation probably makes doing something new or different difficult. Though I didn’t have time, I wanted to write about writers and artists who totally switched styles at the the end–that’s a fascinating phenomenon.

Your point about the public being happy with any feeble scrap as long as its from the artist’s hand is no doubt true. Wasn’t all the fuss about deKooning’s late (probably inferior) work is that it maybe wasn’t actually his? But the public would have been happier with poor work they knew was his than good work that might not have been.

I am beginning to think the opposite way, excepting changes in artistic expression due to cataracts.

In my earlier post, I had a negative view on changes in artistic expression due to neuropathology. But now, I have become interested in these transformations: Humans as experimental preparations.

I am pleased with my plasticity. My Google alert on Alzheimer’s disease told me today that in ‘normal aging’, it is the whiter matter that degenerates first. Remaining able to change my mind means that all my white matter projections are still functioning.

Birgit,

You comfort me. I change my mind a lot.

Sunil, McFawn and i think similarly. Although I’m normally suspicious of the Formalist approach, it seems to me that we are different from minute to minute, hour to hour, and certainly decade to decade. So while it might be visual “degeneration” changed might be caused by wisdom and knowledge — or disillusionment and sarcasm — or the death or birth of a loved one. A Fromalist imperative when looking at art is to look at the art, not at some notion of what the person had troubling her. And I have a sneaking agreement with that at times.

It’s very hard to honestly assess work when you have a context that places it _against_ the past instead of _beside_ earlier work. New work tends, human nature being what it is, to be seen as “progress’ (better than earlier dabs) or “regress” (why did she mess with success?) Sometimes the artist is forgiven (“ah well, it was time for something new. But of course, she doesn’t quite have a grasp of it yet”).

The paradox is that context is essential — and yet we can never have the full context. Was it 3 years? 5 Years? that Irwin spent trying to understand the line? ANd in the meantime, his wife left him (understandably, I would think). So as usual we are left with fallible human judgment. But I much prefer to think of the art as coming out of the fullness of human experience, whatever that is, and made richer by human frailties.

Well, it is morning and I’m still on my first cup of coffee. The sun is shining on the new snow and life seems rather bright.

Sunil, McFawn, Birgit, June:

On the home front we’ve been watching Steve as he deals with his cataracts, and I think that you’ll agree that he is getting better with time.

Otherwise I’m reminded, perhaps, of John Sloan, born within miles of June, who was a driving force in the Ashcan School. He had a slashing and perceptive brush, which degenerated into pained hatch work in his later years. This later output, if I remember correctly, was ill received. The very urban milieu – the soil in which he had blossomed – lost its fertility over time, and he lost his.

If an artist has won recognition for work we judge outstanding, it certainly makes sense to presume that there is something to be learned from later work, even if our reaction to it in isolation is less favorable. I do find Monet’s later painting fascinating, though I admit I’d rather own the earlier one. As June implies, it’s the change that deepens our appreciation, just as with the differences in Angela’s paintings in the previous post.

If we know something biographical about an artist, I don’t see the point of trying to ignore it. At the same time, it’s all too easy to draw facile conclusions about how a life event influenced the art, and I tend to be quite suspicious of such accounts. It may be true in a sense that all expression is autobiographical, but taking that too literally seems narrow and impoverishing of everyone. I don’t much like the word transcend, but I think it’s something we can all do and art can help us realize that.

It is fascinating that visual problems and deterioration of other brain functions due to drugs and alcohol leads to greater abstraction – Monet here, and Rothko and Turner as discussed in my earlier post, see comment #2.

Birgit,

That is an interesting point, but I wonder if it isn’t what one would expect a priori from a diminishment in capacity, especially ability to see clear detail. On the other hand, it seems quite plausible that a painter with failing eyesight might take to rendering in detail small, still-life subjects that can be brought up to the eyes.

Doing a search, I came across an amazing British project, called the The Living Paintings Trust, to make paintings accessible to the blind and near-blind, which works on the following system:

1. Raised images, known as thermoforms, which explain the special shape and characteristics of the pictures that are being “looked” at through touch;

2. Audio descriptions which tell the stories of the pictures, describe their wonderful visual features and provide instructions for touching and interpreting the thermoforms;

3. Colour reproductions of the pictures which, very importantly, make it possible for the packs to be shared with sighted friends, family and peers.

Birgit:

Cezanne, too, painted those airy watercolors in his later years. Did his work reflect a visual change or degeneration? Anyone here know?

Speaking as something of an elder, I would submit that a perceived shortage of time and opportunity can play a part. I’m 20/20 with glasses, yet one of my controlling impulses these days is to simplify – to get down to a virtual twenty five words or less. Part of this, I believe, is in an effort to shed excess baggage and gain efficiency, knowing that my personal reserves are beginning to run low.

Steve:

I was surprised by the degree of enthusiasm that blind people displayed toward visiting the art museum. The extension exhibits department had things that folks could touch, but it went beyond that to something of a desire to be enveloped in an ambiance of visual celebration.rs

There is a two-part video on NewArtTV about Wolf Kahn, who says his painting has improved as a result of his reduced his visual acuity due to macular degeneration.

Steve,

Does Kahn’s experience bear any relationship to Tracy Helgeson’s comment last year that was something like the worse the quality of a photograph, the better suited it is for making a painting of it ?

Well, Tracy’s work, at least what I know of, starts from a scene represented, which she then abstracts and modifies, making no attempt to convey photographic detail. The blurrier a photo, and the more altered in color, the more it will look like one of her lovely paintings. So maybe it helps in that way. Another possible reason is that the blurred photo emphasizes only gross composition, but leaves one free to imagine the rest.