This is a long tale and tail, as you will see. It has several segments.

Geologic time has become entangled in my head with my own mortality and the miniscule histories of places I inhabit. When I was working with the John Day Fossil Beds, trying to imagine millions of years of volcanic explosions that sculpted the Earth and captured skeletons, I thought I had encompassed an enormous time scale — the Cenozoic Era, 65 or so million years of movements of the Earth’s crust, of upheavals and drifts and tectonic plate movement. The Cenozoic is the era of mammals, of riotous foliage. At the very tip of the Cenozoic era, the Holocene Period, humanoids appear –our own time in history, our funny human shapes and adaptations and renderings of the world. There was little evidence of the Holocene in the Fossil Beds Monument area.

Later in my year of the Cenozoic, I was asked to do a piece for an exhibit called “It’s good to be green.” I started to think about the age of the Earth (4,500 million years), which was 4,435 million more years than the Fossil Beds encompassed. It was a staggering number. As I was working through ideas on green (i.e. “environmental ethics”) and the gentle world in which we live and the cataclysms that we can bring down on ourselves, I had a moment of clarity.

It really doesn’t matter in the long run what we humans do. We are but a wink in Ma Nature’s eye; she has survived far worse than our ruinations.

Even though the Earth will readily survive whatever toxic soup we envelop it in, humans may not survive. Or if we do, we will survive in an impoverished state, impoverished in natural imagery and experience and wealth of wonder as well as with fewer resources to feed and clothe ourselves.

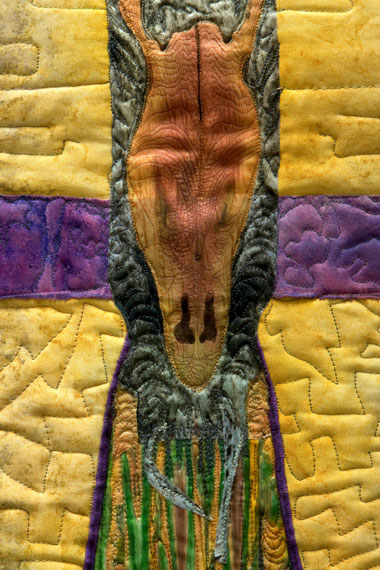

So, the textile art I contrived took as its title: Not to Scale. Even if we are only a blink in Mother Nature’s eye, I decided to hope that we might extend our visit on the planet to a wink rather than a blink. One scientific wag opined that he was a Cenozoic patriot, a jingoistic lover of his own world, and was rather inclined to fight to keep it as it is. Not to Scale sets up the Earth’s 4,500 million years on one side of a 45-inch-long art work and the 65 million years of the Cenozoic era on the other. I too am a Cenozoic patriot and would like it if we could be responsible enough to our own kind to stick around a bit longer. The Great Beast advances. We should take measures.

As I was showing my family the art I had finished and was talking about its meaning and the meaning of life and existence and how I was going to spend the next two months of my life and existence, my daughter (who has her own scale of existence to contend with) suggested that my next big project might be to expand the 65 million years to 4,500 million years and make them To Scale. Having (visually) celebrated the Cenozoic in Not to Scale, perhaps I should visualize the entire history of our living quarters.

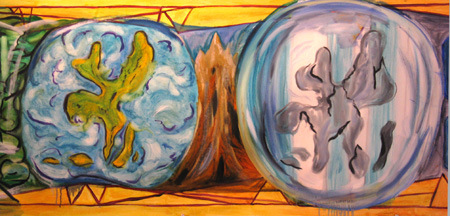

Hence, the modest notion of making visual illustration of the Earth’s billions of years of history, a 22-inch by 15-foot oil painted canvas.

I’m nothing if not ambitious.

And then, I reached that stage of despair which some of you will recognize — the point in a big project when you realize that the work you have done is not merely inadequate but boring and anxiety producing. In this case the anxiety was not just about the project but about my capability and my life’s work and the inordinate spans of history that humankind faces and the ruin that my daughter and granddaughter would be facing – well, you get the idea.

This state of mind, one that I always fall into at some point in a project, rarely extends more than a day or so. I circle the project and/or the ideas, and even if I can’t retrieve the work from its utterly failed state, I know that I’ve learned a lot from attempting it.

So, I ruminated, while waiting for the worst of the despair to pass. And my ruminations pointed out that not only could I never artfully render the time-line of the Earth’s history to scale, but that it was an impossible task to have set myself to. As my research showed, even at even the highest level of abstraction (or most dummied-down version of Earth’s history), the scientists disagree about the time-line. When it becomes give or take 50 million years, we are talking about a span of time equal to the entire history of the Cenozoic. Give or take 50 million years sort of wipes out the notion of scale, at least a scale my frail human mind can comprehend.

Moreover, while I was painting the Illustrious History of the Earth, I was also investigating (visually) the dog, Pocatello, who belongs to Mariah, the home-schooled kid up Basin Street, who lives in a trailer, likes reading but not math, and loves the photos of her little world that we have put up in the studio where I’m pretending to delineate the whole world and all its history.

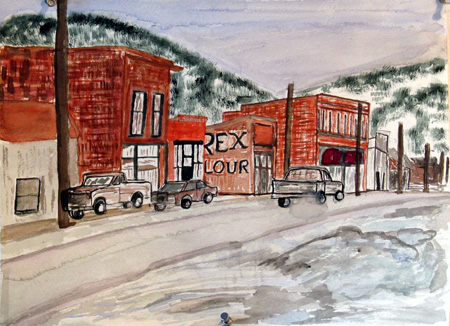

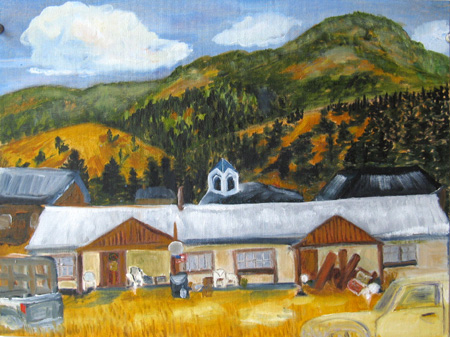

I am surrounded by history; the building we are living in has a plaque reading “Hewitt State Bank 1906 / Later Neiagle Drug Store / Masonic Hall–chartered 1904”. Timbered mill remnants and mine tailings jut out from the hills surrounding the town; Teresa, who waits table at the Silver Saddle, has a son who works in a gold mine nearby.

What scale could encompass a century’s history of a tiny hamlet at a wide spot in the road, the dirt of which dates from the Cretaceous (the name of the era sounding fixed but the dates wobbling within a 20-million-year span), which is being dug up by a guy who wanders past my studio windows talking on his cell phone?

And so, I am reworking my notions of that long stretch of canvas; I’m trying to make it less boring. I’ve stopped reading about cyanobacteria and Rodinia and Pangaea. I’m just looking at the shapes and forms and movement, seeing that I’ve got a bunch of small panels with roundish things squirming and spurting that need to be pulled into a coherent visual whole.

What we know is never to scale; it’s always a confused, somewhat incoherent muddle of this instant of time backed by Cretaceous gold deposits. Art can only capture what it captures, stopping and fixing some tiny speck, an instant of vision scaling everything from the wink of the artist’s eye.

This blog has no questions — or it contains all the questions but no answers. Take your pick.

And here’s a link to a bit about Basin — also not to scale, but throwing in another soupcon to add to the muddlement.

Merry Christmas, everyone.

What a great ambition for a project! It’s always better to be too ambitious then to be too modest in art. Your failures will be more interesting than some people’s successes. The geometic framing creates a visual through-line for your “history”…really interesting work.

I like your ideas about the idea of things being “not to scale”. That’s a perfect phrase to describe the artist’s inclinations.

Artists tend to see things on a different scale–studying what others consider trivial, illuminating the idiosyncratic and small, or pulling back and seeing the big-big history of the world picture when others focus on the day-to-day. A lack of proportion might be a good thing for an artist.

McFawn,

“A lack of proportion might be a good thing for an artist” — what a concept! It turns a whole lot of traditional ideas upside down. And certainly, when I think about the work being done by the artists on A and P, your aphorism rings true. Think of Jay’s ladders and Steve’s closeup of horses and waterfall.

When I am photographing things, I always include an “establishing” shot — and I almost never use it in any way — except perhaps to sort out my understandings of the other images. I wonder if one needs a sense of proportion or scale in order not to follow it.

Thanks for the comment.

June,

I’m not sure why you’re worried about uncertainties of a mere 50 million years, only 1% of your timeline. That seems quite accurate, and is certainly well within the typical size of your segments.

But why should a timeline be linear, anyway? Cenozoic patriots should have a perspective like New York’s view of the country.

Not to mention that (your artistic conception of) history could be considered as fractal (scale-invariant), implying that your depiction of any-size part works for smaller or larger parts, as well.

But as I’ve seen with mine own eyes, there’s more than one way to untangle a Gordian knot. Though quitting has a bad rep, knowing when to do it is a key factor in long-term success.

Here’s a PS to the original post:

Yesterday morning I took the scissors to the 15 feet of canvas, and it felt very good. In fact, one small portion so delighted a viewer that she now owns it.

Jer also sees a piece that he covets — he’s a stickler for standards and has a kind of scientific mind. His notion is that if it isn’t precise (or as precise as possible using all the latest scientific information) he believes it’s better to call it by another name. So now he’s admiring the abstracts that I scissored from the illlustration.

A rose by any other name might be a lily.

June:

You employed a big pair of interregnums – they come in cometary, volcanic, ice age – as you tore into the fabric of time. Frankly, I was looking forward to further developments with your project as it correlates with that linkage thing I am doing.

I remember an educational display down at the natural history museum. An inch or so represented the sun to earth distance with Pluto pasted on a nearby surface. Proxima Centauri, we were told, occupied a jungle somewhere, etc. It was a clever way to put it all into perspective. And in Hindu terms, these large numbers are as nothing.

Jay,

What “linkage” project are you working on? I know of the “links” of wood, of course, and you stretching and compacting of them. Is that it — and if so, how…..

I am now started on a new project for the Back Wall (which is what I have taken to calling the place where the scissored pieces are scattered.) This one is a bit more humble — maybe 10 feet long (or even less, I haven’t measured) but I’m starting with pieces, not a single long canvas. It will be Basin Montana mapped by June’s Eyes. It’s early days yet, for sure.

Happy holidays to everyone out there.

June:

The Ides of March and now the Eyes of June. The better to map you with my dear. Ten, schmen, just as long as you get a handle on that dreadful fifty-million-year business. Frankly, I’m getting very happy over your form and color integration. It has a kind of essence about it.

Me, I’m hunkered in my burrow for the winter, pushing out the occasional holiday light. I give the odd glance at the Q and A chain – my Art Link Letters – and wonder what it would take to have it, or something like it, cast in aluminum. Otherwise, I contemplate scoring a chain like one scores music – and that’s what caught my eye with your Basin, Mont. Epochal Fifteen Feet.

And I hope that there’s a little booze and tinsel to be had at the Refuge – every form thereof having its price.

Hi Jay,

ah, scoring the aluminum — what a grand (and scary) idea! Just the aluminum itself, with its expenditures of $$ and psychic energy tends to frighten me.

I’m reading a biography of Jacob Epstein (sculptor American/English 1920’s forward), left here by one of the former Refugees (yep that’s the official term — used by all in the know). He Epstein, that is) bought marble by the ton, as well as African sculpture by the auction lot — and he kept at least 2 mistresses and a wife and a pack of children. Now there’s a challenge. Don’t ask me why I think of that except the book is here beside me and the expense of aluminum palls beside the expense of mistresses and children by them….

We saw the work of Jerry Rankin at the Holter museum in Helena on Saturday; he is doing monoprints of musical elements — I can’t call them scores, exactly, they were more like a sense of musical place. http://www.rankinart.com/

The sense of place was very strong what with the Australian Aborigine paintings exhibiting in the gallery just beyond.

I also have a glass of wine beside me, so the drifts of snow outside are decidedly charming rather than threatening. The turkey is thawing and the cranberry sauce is in the can, so we are prepared for a good session of work and joy. Good cheer to all.

June:

It sounds like this Epstein fellow had a lot of brass.

I would have to assume that the aforementioned glass of wine is now in you. Thawed turkey can be delicious, especially if prepared in Basin.

I must have mentioned the musical patterning affair for some subversive reason, as I must now come up with something. A lazy big talker I, given to grand announcements, and surly when called out.

Luckily, Jay, my memory gets shorter as my age elongates, so I’ll never remember out that I “called you out.” When you arrive with musical patternings on your ladders, I will be totally enthralled — and surprised.

And the turkey was delicious, as was the Merry Widow Radon Health Mine, where we hiked, while it (the turkey, I mean) cooked. Watch southeastmain for photos of the brassy merry widow.

June:

I doubt it.

June,

Geology is in my blind spot. While I enjoy looking at fossils,my mind still revolts against imaging eons of previous life. Perhaps, I am too caught up in the minutiae of today’s life.

Birgit,

That might have been the point of my attempts and my despair — that blind spot of some millions….

June:

I expected you to wonder what I doubted.

One should seize the chance to contemplate a weathered rock in a quiet environment. You might find yourself drawn into the eons that it represents. I remember coming back from such an experience with a needed priority adjustment, only to lose it to some workaday emergency.

Mind you and Jer watch out for that Radon business. They may call it Merry Widow, but you might turn out to be the one they have in mind. They might be luring innocent artist types with promises of free rent and Refuge and with a nice explorable mine thrown in. Are any merchants offering fresh sausage? Is any of the clothing in the nearly new store suspiciously spattered with paint? Did the studio smell like Clorox when you fist entered it? Our numbers at A&P are thin enough as is.

June,

The closest that I have ever come to understanding geology is from viewing your Miocene.

Jay,

I’m trusting my exposure to the RAdon mines will help me with my witchcraft (lit allusion alert — I just read your comment on your current post).

Birgit, thank you. You make me believe in my work again.