I’ve recently read two fascinating books by cartoonist Scott McCloud: Understanding Comics and Making Comics. There is significant overlap, but I would choose the first for greater emphasis on art and graphic design, and the second for more emphasis on storytelling and practical matters. It was well worth reading both, even though I have no intention of drawing comics.

McCloud has a gift for simplifying without oversimplifying. For example, he neatly breaks down the choices to be made in writing with pictures into selection of moment, frame, image, word, and flow. He discusses these elements while keeping in mind the bigger picture, using them to help us understand what comics artists do and ways they can do it. They also serve in analyzing genre and cultural differences, as in his appreciation of Japanese manga. Especially interesting for me were discussions of closure–how we mentally fill in the transitions in a flow of discrete images–and the “masking effect”, the phenomenon of simple, abstractly drawn characters being more effective in leading us to identify with them, rather than observing them.

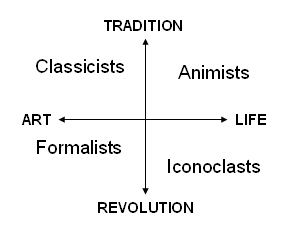

But what I’m bringing to A&P now is a breakdown of artistic approaches that McCloud outlines. Depending on where one falls on two axes–favoring tradition vs. revolution and concerned more with art or with life–one is roughly classified as Classicist, Animist, Formalist, or Iconoclast. The diagram below shows that Classicists are strong for art and tradition, Formalists also care about art as art but favor the new over tradition, etc.

Despite all the necessary caveats, this scheme provides a potentially interesting launchpad for discussion. Its explanatory power, if any, stems from the observation that a particular artist tends to favor one perspective, and others to a lesser degree, but seldom feels drawn to the diagonally opposite postion. All perspectives are important, and McCloud gives many examples for the case of comics.

For myself and for now, the best fit is probably the Formalist corner: less concerned with specific content (life) than with how it is rendered or transformed (art, form), and much more interested in finding something new than in following a tradition. How about you?

Steve,

I read one of the McCloud books and thought it a model of clarity and insight. I can’t remember which one, but I do remember thinking that it gave me more information about basic art and design than the community college course I had taken in basic design. I’m very high on him — may have to pick up both books from Powell’s when we return –I gave my copy to my granddaughter.

But your main point is interesting — yet it seems to me that in examining my interests that I make a diagonal move.

I am very interested in “life” — Basin Montana’s trailers and mine tailings and wheeled vehicles and dogs and streets. I want to depict them. But I also want not to either sentimentalize nor satirize, both of which would be very easy to do.

So to depict what _I_ see (and for which I have a great empathy and acceptance) I need the art. The art/design traditions — careful observation of design principles and elements — line, shape, etc — are what prevent the paintings (I hope) from falling into sentimentality or sarcasm.

Am I making sense? I think I’m going between animist and formalist.

But of course I don’t have the text here, so I could be completely misreading what you’ve written and what McCloud means.

Unlike you, I am concerned with extremely specific content but have to render it according to traditional (by which I mean definitely through the Moderns) principles.

I’m not certain I understand the definitions of Art and Life as depicted on the diagram. Can you expand on them please?

June,

That would probably have been Understanding Comics (1994) that you read, the second is from 2006. I recommend the first for those interested in general art/graphics art.

I think you’re getting the distinctions right. Animists like to “just put it down,” working intuitively without great concern for technique or novelty. This is certainly an honorable pursuit, but one the specific subject matter that appeals to the artist may not compel others, who might be interested in other qualities.

I should add that though I may not photograph a cottonwood because of an attachment to that particular tree, once I have decided to photograph it, perhaps because of some formal aspect, I am very interested in also preserving its specificity. Pure formality is not so interesting, while I do find an inherent attraction in perusing details.

Jane,

According to McCloud’s definitions, “classicists and formalists share a focus on art for art’s sake, in contrast to the animist/iconoclast’s tendency to see art primarily through life’s lens.” For myself, I’ve been interpreting it roughly as a form-content axis, but feel free to spin it however it works for you!

McCloud emphasizes that these are not sharp distinctions or prescriptions, but a rough way of thinking about artistic tribes having similar personalities/approaches.

Steve and June,

Are you starting in opposite corners and then converging diagonally?

According to Wikipedia, iconoclasm is a pretty fancy concept. Can you name a visual artist who is an iconoclast?

Steve:

Help me here. Could you cite an example or two of each of the four kinds of artist?

Jay,

Sure, I’ll stick my neck out with a quick set of examples. Any could be argued about, which might help me with my art history:

Classicist: Ansel Adams, Lucian Freud, our own Hanneke

Formalist: Frank Stella, Jasper Johns, Mark Rothko

Animist: Russell Lee (of the LOC photograph of the homesteaders), Van Gogh, the Sunil of his portraits

Iconoclast: Andy Warhol, Cindy Sherman, Jeff Koons

Steve:

Thanks. Would Chuck Close fit the classisist designation? How about the other super realists? (Chuck 0ften gets thrown in with them)

Frank I can see, until he goes off the reservation with his ebullient post-protractor series. But your point is that Frank, exemplifies classicism in his earlier work.

OOps…

Meant to delete that comment and come at the subject from another direction. We could dissect a multitude of artists and find in the end that nobody of consequence fits any sector neatly. Actually we could come up with any number of two axis diagrams with differing terms.

Yes I would agree that nobody fits any sector neatly.

Regarding artists who cross diagonally, I think of Mondrian and Kandinsky as formalists who were also animists, if you follow the def of animist as one who believes that objects have souls.

On the other diagonal, I think of Cindy Sherman and Kara Walker as iconoclasts yes but with feet firmly in Classicism (rational, non-emotive).

First, a reminder that neither I nor McCloud has any stake in classifying particular artists in this scheme; we just find it an interesting way (one of many) to think about an artist’s concerns. I’m sure Jay’s right, other axes could be much more illuminating in some cases.

Thanks, Jay, I hadn’t even realized Close was a hyperrealist in his early days, I only knew some of his later work. I think of hyperrealists as in the upper half of the diagram, having Classical concerns with perfection of technique, but Animist desire to render a scene from “real life” as exactly as possible. Close’s later use of other techniques took him away from that realism and toward more Formal interests.

Martha, I agree with your assessments of Sherman and Walker. I’m not quite sure why McCloud chose the term “Animist,” but he was using it to mean someone concerned with depicting life in an essentially traditional, straightforward way. In that sense, I don’t think it applies to most of Mondrian or Kandinsky; I think of them as fitting into the Formal camp, very concerned with art and beauty, but of a new sort (for their time).

Martha,

Thanks for the Kara Walker references. Fascinating!