Recently I visited, twice, the Portland Art Museum’s current exhibit: The Dancers, featuring art by Degas, Forain, and Toulouse-Lautrec. Both times I was struck by the marvel of organization that the curators had achieved.

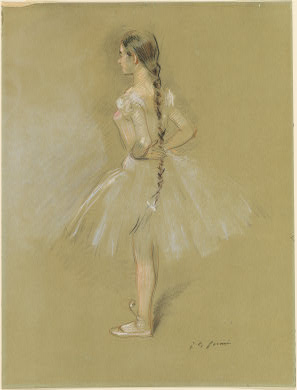

The exhibit begins with an overview — art by the three men — and then proceeds to explore each individually, moving from Degas to Forain to Toulouse-Lautrec. Degas is first, and of course, his dancers are superb. Beside them, in the overview, Forain’s painting of a dancer seems a much lesser image, although the subject is somewhat more personalized. And Toulouse-Lautrec work seems more about shape than about a subject matter — at least in the initial exhibiting area.

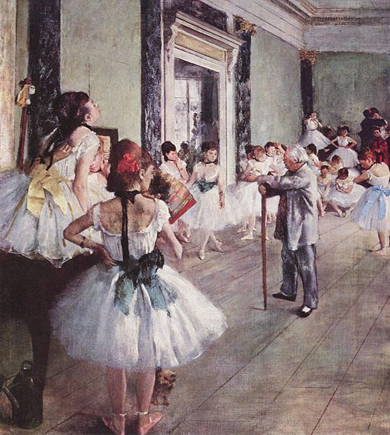

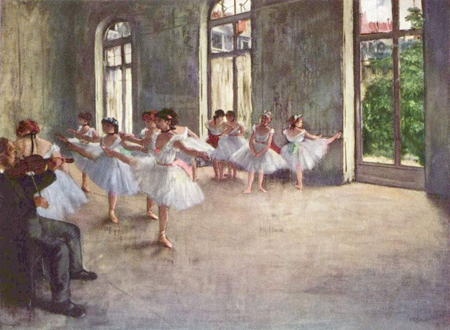

Moving on through the exhibit, Degas‘s work is featured first. It’s exquisite and, at least in this exhibit, is entirely about shape and form and light and composition. While he is an acute observer of human activities and nature in other works, the art at the PAM exhibit features his ability to capture the dancers as beautiful ethereal creatures with wonderful tutus. He has almost no individuals; the dancers, while sometimes exhausted as well as sometimes fragile, are not individualized. They aren’t sexy, even when undressed.

Jean-Louis Forain was influenced by Degas, but what becomes instantly clear as one reaches the section of the exhibit that focuses on his work, he was keenly aware of social inequities. His dancers are children, at the mercy of the fat well-dressed men who prey on them. The men are portrayed as leering, towering over the smaller ballerinas. They are depicted bargaining with the mothers of the young girls; they hem them in with canes and outstretched arms; the girls (for they are all young and vulnerable) are helpless and trapped.

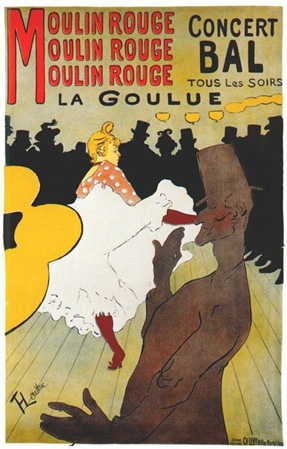

And Toulouse-Lautrec, although at first seeming to be mostly concerned about shapes within his paintings,(“shapes” in the art sense of the word), in this exhibit also observes individual women in their sharpest, most piercing, at the height of their power. In much of his work the men, although subjecting the women in the manner of Forain to leering observation, are put into shadow and the women, by virtue of color and light, have power:

Here are more examples of the differences: Degas. Forain. Toulouse-Lautrec.Both times as I went through the exhibit I found that I initially dismissed Forain while I was looking at Degas. Degas is all about the canvas as beauty, composition as stunning, light which makes lightness and movement. But when I was in the Forain section, I was suddenly, overwhelmingly, sickened by the fragility of the dancers and enraged at the fat rich men who bought them and sneered at them before, presumably, they took them off to have sexual intercourse. I stopped seeing the paintings and could only sink into a world of obscene wealth and human suffering. Both times I became enraged — and forgot I was looking at paintings. I have no sense of Forain’s compositions, although he does depict individual dancers. His men are simply, in my memory, horrifying slugs. Then, coming out of the rage to Toulouse-Lautrec was a great relief. His women are individuals. They have names (Jane Avril, Loie Fuller). They are not vulnerable children, but full blooded women in full command and control. And while Toulouse-Lautrec shows the leering men around such women, he never allows them the upper hand.

My point here is not just to make observations on the life of a dancer in France around the turn of the 20th century, but rather to observe how the set-up and selection of the exhibit worked to process my emotions. In this particular exhibit, after seeing Forain, Degas seemed a lightweight (although elsewhere, he deals with some of the same social conditions; and Forain turned conservative in his older years). And Toulouse-Lautrec was an enormous relief, not because of his style, but because he returned to dancers as human beings, individualized. I was lead through the exhibit by the curators to come to these positions; the art had been selected and placed to make me feel admiration, horror, and relief. It was as good as a first-class drama, a play in three acts, where I moved, not the actors.

And so, I’m thinking about how I present my own work — and how you present yours? Do you mix and match themes and styles? When you put things up in your studio and studies, do you think about leading your visitors through a series of contemplations and emotions? Do you find yourself reacting to your work as a series of dramas, through which you can lead your mind? Or are you doggedly set to have each work be something sui generis, a writing on the blank canvas of our minds?

George Grosz also depicted sexual and other exploitation but without, at least in me, inducing tears. Probably more of a Toulouse-Lautrec style, calm observation instead of, what I gather from your description, cheap emotionality.

I will be thinking about your questions as I will be on the road for a day or so.

Thanks, Birgit,

I apologize for the way the home page looks when it’s initially logged into. I think the problem is something I did, but I can’t find it or make any changes the bring it back to its original conformations. Steve is our resident guru and will have to help me sort when he gets back to town.

What challenging questions! For the last couple of day, I looked at the organization of artwork on a website and in a museum.

In a museum, through the center hall, I walked by pictures of Woodland Artists with striking colors and bold lines to an inside room where I viewed with Russell Chatham’s oil painting, mute colors, subtle lines. The two exhibitions were in jarring contrast.

Within the Russell Chatham exhibition, there was no recognizable organization of the oil painting. But, perhaps, I missed it because I mostly used most of the little time that I had to photograph the frames of his pictures.

The most common organization of artwork appears to be by subject. Taro Yamasaki, for example, list three main topics on his website: documentary, people and travertine architecture. Under documentary, subtopics range from Children of War- Nicaragua/Bosnia, Inside Jackson Prison to Wild Horses. The question is to what extent he organized the photos within a subtopic.

Recently, we thought about organizing Steve’s Winter Water pictures.

My suggested organization was different from Steve’s vision. This makes me think that organizing creative work into a story is much more difficult in the arts than in science where I was used to spinning stories for a manuscript or for a poster – why this molecule may be of significance to embryonic development/neurological disease, the chemistry of the molecule, its cellular or subcellular expression, some experimental manipulations followed by a hypothesis of what the real function (s) of this molecule may be.

As an embryonic artist, I am now organizing some photos for my website and I am musing where I am heading with future exploits regarding different subjects, my emotions, my abilities.

I will continue ruminating on your fertile questions.

We do need Steve. WordPress did not accept the links that I inserted into my comment. Trying to insert the links once more, several paragraphs of my comment were ‘swallowed’ up. I still see these last paragraphs when I try to edit my comment but they are not published.

June,

I looked at the museum web site and couldn’t find anything giving a clue as to what the curators might have been aiming for. Do you think their message was the one you so strongly received? It certainly makes a very nice reading of the exhibit.

I was recently thinking of a certain parallel between photographers and conceptual artists working with readymade objects à la Duchamp. Namely, photographers are usually working with something they find in the world, trying to present it in some way they find interesting or significant. One could think of curators similarly selecting and arranging works to bring out an idea or concept. Perhaps we should consider this one artistic mode, as Karl once suggested for art dealers.

(I’ll have a look at fixing the comment problems a little later.)

Steve,

I don’t know if the curators consciously set up the emotional impact of the exhibit as it is presented. The birthdates of the artists could also have been a deciding factor Degas was born in 1834, Forain in 1852, and Toulouse-Lautrec in 1864).

However, the exhibit was consciously aimed at providing Degas’ dancers and not his social criticism and Forain’s social criticism, particularly of the dancers. Both artists did work with other subjects.

I do think that exhibits are a form of artistic expression and the curators then must be considered artists.