There seems to be an uptick in concern about the separation of art and science and in efforts to join them in some fashion. Though I must say it’s very difficult to assess this sort of cultural trend, and in pessimistic moments I sometimes wonder if anyone knows or cares much about either. At any rate, I’ve come across a recent book that brings together contributions by artists and scientists of various stripes: Findings on Ice, first in a series envisioned by the PARS Foundation of Amsterdam. It doesn’t seem to have made much of a splash so far; I’ve found no reviews or mentions online, except for publishers’ blurbs.

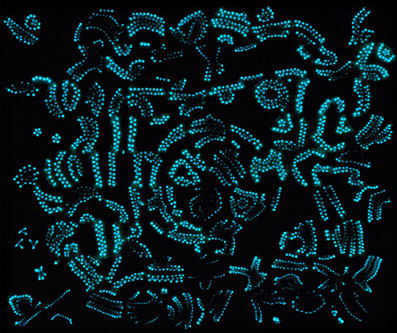

Michaela Frühwirth, Obstruction_1, detail

For me the loveliest find was the work of Michaela Frühwirth, reminiscent of the detailed drawings of Vija Celmins, though abstract in nature. If we relate it to the topic at hand, the picture here could be seen as a jumbled ice field or a micrograph of dislocation lines in an ice crystal. Other artists represent not only from the usual visual arts, but dance, music, jewelry design, writing, architecture, and even cooking.

With roughly 50 contributors, this collection is not surprisingly uneven. That goes for the editors, as well, who have done interesting things with an interesting concept, but also write things like:

So…

This book is a map

This book is not a map

This is a book about ice

This is not a book about ice

…

And they seem to have missed the whole point of broader thinking when they write in the introduction that “…ice is a substance that holds no fossils.” Yes, I know what they mean, but couldn’t they have thought in terms of of a million years of fossil air telling about our past climate, of ice cap troves of lunar and Martian meteorites, of frozen structural patterns that record the passages of a glacial river, as sinuous as any belly dancer?

Perhaps the thing I missed most was any substantive interactions or collaborations between scientists and artists. I believe the foundation sponsors meetings and exhibits where such discussions could take place. The book is apparently meant as an inspiration for such cross-pollination, but it would be nice to have some examples for those who can’t attend any events.

So do you have any good examples of art and science interacting? Mine is Bioglyphs:

Steve,

The most frequent (and alas banal) interaction of science and art now seems to revolve around two areas — microscopic views of material turned into abstract art and computer technology (mother boards and strenuously photoshopped images) also made “abstract.” Oh, and in fiber arts, there can also be found mathematical variations — quilt blocks, for example, lend themselves to this kind of mathematical exploration.

I don’t find these abstractions very compelling, in part perhaps because I personally can’t find any specific “hooks.” If I were a scientist, perhaps I would have a more visceral reaction.

The topic is fascinating, though, and as I think about it, I realize that the “skewed” paintings of Rackstraw Downes and contemporary photographers, such as appeared in Birgit’s post just prior to this one, depict my favorite intersection of science and art. Of course, I didn’t know about the science until I read the article in the Times that you cited in the Downe’s comment section.

So many things to think about, in so many ways!

Steve,

Didn’t we discuss the use of brain imaging pictures as a motif for painting and photography in one of Richard Rothstein’s posts?

In a way, I am collaborating with my physical therapist, trainer and acupuncturist to learn and draw functional anatomy and energy flow in the movement of children.

Steve:

For the life of me I can’t seem to find any mutually enhancing connection between art and science.

June said a lot in her comment. If I understand correctly, she allows for “art” and “science” to be in the same place at once, like a nice photograph, but they need not to be touching each other. The science might bring the subject matter and the art its modes of presentation, but these things are, perchance, placed on a table between them. An equation can be drawn on the board with bad chalk and a rude hand, and, as long as it is legible, nothing is lost. Script the equation on vellum with a deft hand and nothing is gained.

Steve,

When you ask about correlations or interactions of art and science — how are you thinking of science? That is, do you have a field of inquiry in mind that is categorized as a “science”? I’m finding the question a little baffling, but I may have too strongly in mind frankly lovely things like botanical illustration and the intriguing but less overtly lovely things like the graphic quality of some medical printouts (ekgs and such). There is, of course, a long history (pre-photography) of scientific illustration — but I suspect you have something else in mind.

Art is not only about mixing paints and pleasingly decorating a surface: it’s a way of seeing ourselves and the world, it’s about ideas. Science is not only about calculating from equations and producing medical technology: it’s a way of seeing the world and ourselves, it’s about ideas. How much richer would we be, artistically and scientifically, if these ideas could inform each other, rather than remaining separate in different minds that don’t communicate?

For example, riffing on the Bioglyphs image in the post (unfortunately, I’ve never seen or heard more of the project than is on that web site): The patterns of the luminescent bacterial colonies remind me of Australian aboriginal dot paintings (see above), which are quite varied but often have concentric patterns like the ones shown. This in turn reminds me of patterns produced by the Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction (see below) if properly set up; these are self-generated (i.e. one starts from uniformity) spatial expressions of an oscillation in time that is mathematically analogous to the circadian rhythms that are the pacemakers of many creatures lives (if you stir the solution to enforce spatial uniformity, you get changing colors over time, see this video). This represents a kind of spontaneous ordering of randomness in the universe, but it occurs with a certain unpredictability and sensitivity to initial conditions, i.e. chaos. Chaos and order have been fundamental concepts in art and science since forever, and tie into making sense of the world by walking through it and marking it, singing it… A scientist or two who knew more about the chemistry and biology (and had a lot of time to experiment) could probably help an artist figure out how to create a living, breathing, pattern-forming, beautiful manifestation of some mix of all these ideas that would have to be considered an amazing work of art.

Birgit mentioned the entrancing fMRI brain images; I would like to see what a performance/video artist, working, say, with a neuroscientist and a computer graphics whiz, could come up with using a device like this headset to show representations of their mental state while engaged in some kind of performance activity. Even monkeys can use brain prosthetics to manipulate their environment, how much more can we do?

I could go on indefinitely, but I hope this illustrates the potential I’m thinking of. Others must be as well.

This conversation inspired me to take CP Snow’s “The Two Cultures” off the shelf to reread. Snow identified and addressed this problem of the segregation of paths to knowing in that book.

I don’t remember from my first reading whether he does more than name the problem. It seems only to have gotten worser and worser since the book came out and I wondered if there’s a way to address it with the hope/intention of alleviating it. (Symposium, anyone?)

I have a vague recollection of reading about an annual dinner that a foundation hosts that brings its grant recipients together and how, once intial shyness of various stripes is alleviated, conversation rockets around the representatives of the various disciplines.

Melanie,

The most exciting effort along those lines that I know of is provided by Edge. A recent event involving science and art is described here. Also recently, the NY Times reported on an educational program at Binghamton University emphasizing science-art interactions.

I think the problem of separation has gotten worse and better since Snow’s time. Worse because of increasing specialization and difficulty communicating even within a single discipline. Better because even “hard” sciences are becoming capable of addressing questions about what distinguishes us as humans and what goes on in our minds, i.e. they’re becoming concerned with the same subjects as the arts and humanities, rather than seemingly totally different subjects.