I have just finished an intensive (and intense) 5-day workshop in plein air landscape painting. Later, I may indulge myself and talk about the entire process and the 3 locations we painted at, but for this post I’d like to pose a question which comes out of just one location. The question I’m posing is how does one transfer the knowledge gained in doing one piece of art to her general practice? More specifically, how can I hang onto the insights that my instructor helped me gain and use them when I’m working on my own?

The specifics: On Wednesday we painted at the Willamette River waterfront, in a piece of waste ground, just to one side of the Interstate 405 (Fremont) Bridge as it rises over the river. One humongous stanchion was no more than 10 feet from my painting spot. The roar of the traffic was absolutely constant; it was only maddening if you tried to talk to someone. The field was dusty but large, the sun quite warm, the wind constant, and although there were city amenities beyond us on all sides, a chain link fence and heavily trafficed road cut us off. It was a total enveloping environment, not necessarily unpleasant if you sank into it.

That was Wednesday. On Thursday and Friday, we moved the art school’s painting studio and worked on projects based on one of the plein air pieces. I chose to enlarge upon images and ideas that I gathered from the Under-the-Underpass experiences.

Fremont Bridge 1, photo, June 2008

Fremont Bridge 2, Photo, June 2008

Fremont Bridge 3, photo, June 2008

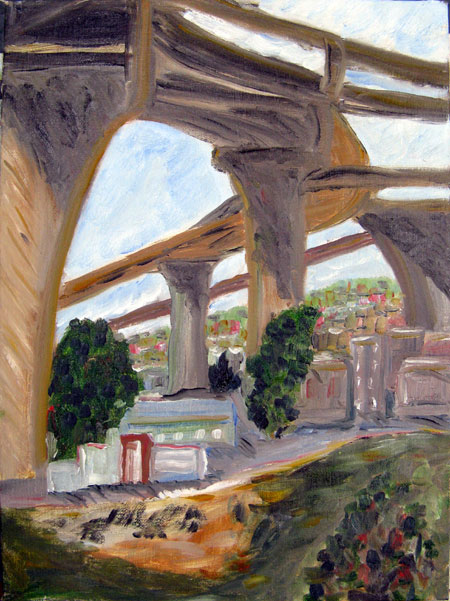

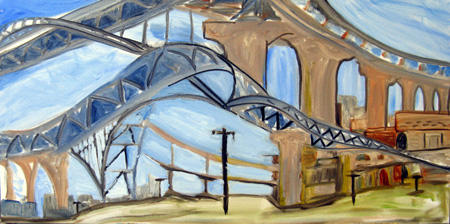

Below are the two on-site paintings that I produced, each in about 3 hours of work.

Fremont Stanchion, 12 x 16, oil on board

Fremont Bridge and Front Avenue, 12 x 16, oil on board

When we went back to the studio for the two days of further work I brought in a larger canvas — 18 x 36 inches — with different proportions than the on-site boards. I had taken a lot of photos of the bridge and surrounds, and so I collaged them into an approximation of the size of the new canvas. The photos were, of course, incongruous with one another — I wasn’t attempting a panorama when I photographed them. But I taped them together so that some of the bridge contours approximately matched. I also collaged structures of the same bridge scene on what would be the top and bottom of the “canvas”, so the complexity of the scene was doubled. (The representation below isn’t the same as I had worked up in the studio; I couldn’t recapitulate at home what I was working from there. But it may give you some idea of what I had in mind.)

Collage of Fremont, Photos

By 3:45 on Thursday, the first full studio day, I had produced this from the collage above:

Fremont Bridge, draft 1

It was clearly not what I wanted. My desire was to bring in the force and power of the structures, a sense of the noise, and its enveloping presence. Instead what I had was swoosh.

At that point, Jef, the instructor, intervened. With the back of the brush, he traced a couple of lines through the paint that he suggested would give me something of the impact that I had in the collage. With 15 minutes left in the class, I took the biggest brush I had and reworked the canvas, like this:

Fremont Bridge, draft 2

The next morning, I faced the mass of confusion that I had left the day before. By the end of the workshop that day, I had advanced the painting to this point:

Fremont Bridge, draft 3

In two crucial areas, the instructor gave me advice that made the painting what it is. Relatively early on, he suggested inserting the telephone pole in the front center. And he showed me how to enlarge proportions and work over the perspective to give a sense of greater intensity, closeness, and distance.

His final suggestion, which I haven’t had a chance yet to act on, was to work the shadows and light irrationally, “incorrectly” a la Giorgio de Chirico.

Each of his suggestions was right on the mark. I doubt I could have carried off the painting without them. My conundrum now is how to see in such a way that I can make my own suggestions to myself and continue in this direction. I am reviewing my notes and my experience (this post on A&P is an important part of the process); are there other ways to imprint my memory and work with the specific knowledge I gained with this instructor?

It is very difficult to see our own work objectively, as another might see it, and most especially as one particular other might see it. One of the benefits of writing workshops (maybe the only benefit, I pretty much loathe them) is to stumble across someone who reads you well. It sounds like you’ve happened upon a teacher who reads you well.

There’s no shame in cultivating the relationship — take another class with him, keep the notes you’ve made on hand and refer to them, email and ask for advice. We don’t need to be complete worlds unto ourselves.

You asked for a mentor in painting. It seems a mentor has appeared. Latch on. Teachers like to teach. Teachers especially like to teach people who are eager to learn. Give him the pleasure of teaching you.

Melanie,

You have written of the process that I have engaged with over the last year or so; I have taken 3 classes with Jef. He is beloved by all his students and he has the same touch with all of them. So it’s unlikely he would ever think of being or want to be my mentor. (There are other more complicated reasons, involving his history, my age and so forth, but they aren’t essential).

The more important question is how does one become self-reliant and independent in making art decisions. I’m pretty well self-contained, somewhat self-taught, and always seeking to be independent and self-suffficient. I am too old to be a groupie and Jef is too remote to be interested in acquiring one. If I can’t paint on my own, producing some simulcrum of what I have in mind, then I can’t claim, to myself, to be successful. Is that making sense?

Time, I suppose, is one answer and continued self-assessment. The company of many artists, which I keep working toward. But I am hoping that some of the artists here would have insights into extracting oneself from dependence upon that external eye.

Thanks for checking in. Now I have to catch up on some checking in of my own.

June,

I think your second painting captures well the strength and impact of the overpass, with excellent potential for a de Chirico-style looming quality if the shadows are darkened. So it seems indeed that Jef picked up on something already there.

But to your question of holding onto a lesson: I think it takes multiple repetitions of the experience with variations that you work out each time. No doubt working with a good teacher is best, but perhaps you can also build on previous lessons with some relatively simple exercises along the same lines. For example, sketch a similar initial composition (perhaps very reduced as in McFawn’s mini-sketches) and try to modify it towards your goal. I think it’s key to make the exercise simple so that it can be repeated often without too much effort that would soon tire you. Though done quite consciously, even in an artificially forced way, I believe that the methods practiced become part of your unconscious style. At least I hope so–I’m working in that way myself.

Steve,

Interesting idea — to work out some exercises to enforce the mind/eye/hand/production. In this case, I would try to work out exercises in which the perspective, or the way the forms filled or loomed or moved in and out of the canvas, produced a sense of tremendous power. That’s what I wanted to achieve in the last draft; I didn’t quite make it, but I was coming close.

I have thought about going back down to the wasteland (Child Roland to the dark tower comes!) and painting more. But it’s 97 out there today, so I might wait a bit.

I haven’t seen any workbooks or texts or references that approach perspective from a direction that comes at you — is in your face — rather than receding. I think the technique is fairly mechanical, if I could just get my mouth (so to speak) around it.

The shadows will be just plain fun and not hard to make work. And the addition of the telephone pole was inspired, but not beyond my capability. It’s that sense of the bearing down upon all the senses of the freeway that I want to achieve. And I want it to include the complexities of the scene that leap at one who is there — it’s almost impossible to sort out the patterns that the engineers must have been working with — that inner city density and tangle that freeways create.

Interestingly enough, another painting I did, of a truck and an apple tree and Mt Hood in the distance, I pushed the truck into the grass, until it was just another element of nature. My fellow students knew I was working on the freeway and wondered why I hadn’t made the truck more pushy, more in-your-face. But of course, I didn’t because that wasn’t the point in that painting.

June,

Looking at a few paintings by De Chirico on the web just now, its seems to me that the tension in some of his paintings, such as the Red Tower, derives, not just from shadows, but also from the just slightly off-center positioning of the protagonist in the painting.

Recently, you mentioned that the notion of the “sweet spot” at an 2/3 place on the image has been turned into a cliché in your comment in http://www.artandperception.com/2008/06/re-center-vertical-lines.html.

In your own work, I just checked on your web site again, you often put the ‘protagonist’ at or near the center of your textile art avoiding the cliché sweet spot.

To be contrary, I love the airiness of the ‘Fremont Bridge, draft 1’. Your draft makes me want to be at that scene and have a good time – though, the lamp post is slightly ominous.

What I am musing about – with respect to my own progress – is the issue: Learning from a teacher versus going deeper into one’s own feelings.

Birgit, I think your issue: “learning from another versus going deeper into one’s own feelings” resonates with me. I am stubbornly insistent on my own, often perverse, silly, or awkward vision. It has to do with my age, I suspect. Even as a “good girl” I can’t deny that if I don’t do it now, I’m not going to have much later to do it in. So I insist on my own feelings — but —

The difficulty, I find, is that I have very strong very deep feelings about some subjects (like the Freeway structures) but lack some of the technical skills to produce a facsimile of the feeling. Technical skills are supposedly easier to learn, but that’s a generality that can be crushed when tied to deep personal feelings and a need to express them, not what the technical instructions carry one toward.

Of course, artists have always bemoaned the difficulty of getting their images to match their ambitions, but that’s feels like a separate problem for me at the moment.

Thanks for checking in. The airiness of Draft 1 has, alas, gone under under great gobs of black paint. Maybe someday I will revive it in another version.

And a postscript thought: I wonder if composition is particularly susceptible to becoming cliched (re your comment about the “sweet spot.” For hundreds of years, of course, the center was it. Then we discovered Japanese art and went all assymetrical. Now here I am, complaining that the center should be holding again.

Birgit,

The two sides of your issue are not completely opposed. A good teacher is one who helps you go deeper into yourself. Even if the teacher doesn’t understand you so well, they should be able to provide tools that will assist. Ultimately, of course, you do it on your own.

June and Steve,

So far, I have been afraid to take instructions in oil paintings. My sense is to first get my feet wet and then look for a mentor. I am probably dead wrong on this. Perhaps, when I am ready, a mentor will show up for me as well.

With respect to the airiness of the first draft, it reminds me of a huge road net that I watched slowly coming into existence a few decades ago where the Cross Bronx Expressway connects with the Throgsneck and Whitestone Bridges.

The very long time that it took for the pillars to be erected, it made me think of a scene from a Greek temple site – vertical, pointing into the sky. The roads running on these stanchions are elegant and could not be reproduced with ‘great gobs of black paint’. In short, your Portland and my Bronx experiences do not match.

June:

I’ve been looking at this post without enough to say, or maybe too much, unsorted.

I remember those overpasses vividly. They roam over the cityscape as a gentle roller coaster and my impression was that I could sail into space at any moment.

More anon about the student/teacher relationship, which for me is a very tenuous thing. But I would like to say that, for me, your second painting is remarkable and one of the best I have seen you do.

Birgit,

Your reluctance is understandable. I sometimes say I went to the Fossil Beds a quilt artist and came home a painter. But that simpifies, even falsifies, the years I spent circling the processes of drawing and painting while I was “really” doing the textile work. I started out with a drawing for dummies class (had to take it twice!). I took a truly dummied down beginner’s oil painting class, just to see what materials were used. I took some community college basic design classes. I fell into a figures-in-watercolor class, which bewildered the instructor, who couldn’t figure out why I was there. I had an online acquaintance critique small paintings (watercolors) that I did. I took the Field Guide to the Human Figure class. All that while I was definitely not a painter nor a drawer; ostensibly I was just honing my artistic eye, hoping some skills would transfer to the textiles.

Then I went to the high desert, without a sewing machine, to make art, and came home with the realization that painting was what I wanted to learn to do. At that point, I had circled the subject enough to feel like I could take respectable courses from respectable instructors without embarrassing them or me.

So, tell yourself that your forays into art are really to enhance your photography, which is already a well-established skill. That way, you won’t take yourself too seriously — no one expects a photographer to be able to paint (add snort right here).

And while I’m telling you all this, I’m also thinking, hey, what the hey — this isn’t brain surgery and no painter has ever caused any one to commit suicide, so why not just jump in and go for it. I didn’t, but then, I didn’t know I wanted to. Now I do and I am.

Jay,

Thanks for the comment on the painting. I appreciate it and am hoarding it for the times when I feel myself fail miserably. I find painting is a manic-depressive sort of activity — I jump from the high to the low with great regularity.

and about holding the knowledge –I could have guessed that you were far more rebellious about student/teacher relationships than I am. But then I started a tad bit later than you did, so my rebellious youth was spent arguing with my philosophy teachers. Now that I’m old and wise, I know much less. So I need teaching more.

June:

That term ‘rebellious’ is going around in my head. Was I rebellious? More offish maybe. I encountered art at a time of personal turmoil over religion and I was going through an extended period of doubting authority. This led to a habit of hearing the teacher talk, but at arms length.

It appears to me that one of the things that you brought over from quilts to painting is an affiliative impulse. It’s dangerous to generalize, but some might see something congregate about quilting. There’s a ‘we’ sense in it that I don’t find so much in painting. I would think that this sense of unity in purpose is for keeping and carrying forward in whatever form it can take. And the form here is the didactic environment. It may be hard to find mutually supportive relationships within the student/teacher dynamic.

Jay,

I was going through an extended period of doubting authority : I still suffer from this condition. Actually, it is more than doubting, in many cases, it is laughing at.

June,

Thank you for sharing your adventures!

Today was a tough day. It helps having friends.

Birgit — the pleasure is definitely shared. Thank _you_.

Jay’s comment about “affiliative” impulse feels quite right to me. I don’t think the quilted art and the “affiliative” are necessarily joined, at least not for me, as I always disliked getting pegged into traditional notions about quilting bees and (women’s) communal work.

But it’s true that something about my nature wants more than the solitary processes. I like working beside other people, sharing a common language and common goals, common jokes and common experiences. Because I like that in the rest of my life, I bring that pleasure to my art life, also.

I was thinking about a project that I may be embarked upon, painting bits of the little hamlets that make up the sparsely settled eastern 2/3 of Oregon. The thought of painting the habitats of those people who may feel a bit isolated and ignored seems part of the commonality that I hope will resonate between myself and others.

I’m reading Suzi Gablik’s “Conversations Before the End of Time,” in which she speaks of art as a communal activity. She hopes her conversations (in the form of interviews) will entice people to talk rather than argue and find common ground rather than differences. I can’t go as far as she does in optimism, but it is something I would hope would be part of my art.

So “affiliative” is a compliment (and like many a virtue, it is also a vice.) But I won’t speak to that tonight.

June:

As you are appearing in your hamlets so too will my son Adam be appearing this summer in Hamlet at Stan Hywet Hall. He’ll likely be wielding a big thespian brush.

Your notion, to me, of painting those settlements in the far Oregon is, indeed, a shining example of your impulse to connect. Bringing comfort to the stranger through the painted image is a fine idea and one to surely bear fruit, as it has so borne in examples that you have shared.

Did you see George Bush Sr.sky dive? He was attached to an expert and it seemed cozy withal. You might adopt a method from his example. What better commonality than to literally paint Hand-in-glove with another. I can see a big glove in which two hands could fit overlapping. Yours could be upon the other’s as it might be with you and your computer mouse. Best the other person be relatively small as you might have to wrap around like a golf pro correcting a duffer’s swing. What say?

Jay,

If I am making the correct leaps of imagination, it seems you are saying maybe I should be painting with a kid, guiding lightly, etc.

Nope, can’t do it. Kids are too high maintenance for me. I’m sure there are teachers who can take them in their stride and also do some work of their own, but I have been trained too seriously in the art of being on-call to be able to paint seriously with someone who can’t be treated as an absolute peer (ie –able to find the bathroom, retrieve the water, clean the brushes and bat at the wasps without my aid). I did paint and draw with the grandchild around Portland when she was younger and we had fun. But it was clear that I was a) not teaching her to paint and b) acting grandmotherly unit at all times.

Of course, I could try to get Jer to paint — he’s pretty self-reliant. But I think he might not like the wasps!

Thanks for the idea. One of the difficulties with getting artist-in-residency posts is that they always want you to spend some time teaching children. My muttered mantra is, “I don’t teach!” And that’s in part because I have too much respect for the art of teaching to try to mix it with my arty painting.

June:

Granted that members of the Bush family can act childish at times. But, no, I saw in my mind’s eye an adult. The thought was that you would commune, hand in or over hand, with a peer, but one of a manageable size.

Jer might fit the size requirement but I’m afraid that the product of your mutual efforts might be a cross between a cityscape and a Wickipedia article.