I’ve always liked this photo by Steve Durbin.

But what does it have to do with tango?

Let’s look more closely. The landscape has sharp and repetitive features. This regularity creates a structure through visual rhythm. The water is something quite different. It is a smooth flow, it is bold and bright, yet soft. Both the land and the water have motion. You might say, the water is moving and the land is still, but that is not correct. This is a photo and everything is still. The movement is not literal movement, but the suggestion of movement of a different sort, of visual movement — it makes your eyes move, it makes your thoughts move, it is psychological movement. This is the magic of photography(and drawing and painting) — putting movement and stillness on an equal footing, giving each the potential to move.

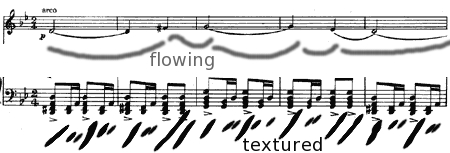

Above the photo I’ve placed the opening of the most famous of all tango tunes, La Cumparsita. Here it is again, below. You don’t need to read music to see some basic structure. [You can hear a old recording here]

Look at the second line of the music above: it looks jagged and repetitive, rhythmic. In contrast, the solo violin on top begins a melody with one long note, followed by a shorter one, then another long one. At a musical level, this is very much like Steve’s photo. The river is the melody, the land is the textured rhythm that create a structure for the river to run through, for it’s form to take on the meaning that it does.

We’ve looked at some music, but what about the tango dance itself? The goal in tango dancing is to express the feeling of the music as a totality, which means, in part at least, to express these two elements simultaneously — rhythm and melody. The complex rhythm is expressed with the feet, the melody with the upper body. I’m trying to learn and I can say, it is not easy! The image below is a link to some real Argentinian dancers (you will need to scroll down on the linked page to find this video).

This video (click image, scroll down) shows the feet marking the rhythm, the upper body the melody. The linked site, Tango and Chaos, is an excellent source of information.

A river flowing through a landscape, or an old tango tune, both are pleasant in and of themselves. To interpret them, into a picture, or into a dance, requires some special ability and awareness. What I am arguing in this post is that part of what we need as visual artists is to accomplish multiple tasks at the same time. We don’t necessarily have to do everything at once, as artists, but in the final outcome, it must all be there, working together. The tango dance, expressing the melody and rhythm together, seems to me both an informative and inspiring metaphor, or perhaps example, of what we are doing when we are at our best making still images.

Have you ever found inspiration for your artwork in (what seemed like) unrelated disciplines?

How to Store Oil Paints

How to Care for Brushes

Frames and Framing

Painting from Life vs. from Photos

How to Blog

Karl, very interesting post, especially seeing the musical score w/ your markings and comments.

While I’m always looking at paintings, most of my inspiration comes from other things, especially from reading (everything from fiction to science), and from music (especially songwriters). Had a big breakthrough in grad school when I realized how the Beatles’ use of fictionalized personal experiences as points of departure could be applied to narrative in paintings.

Karl,

I can’t believe you come back after long hiatus and write a post as if you’ve been in my brain! But before I get to that: I really enjoyed listening to the music while viewing the photograph. I could very easily relate things I was hearing to things I was looking at, with the swooping flows and the negotiation of more difficult stretches. The general sense of energy and unpredictability in the music also correspond very well to the actual behavior of that stream (Coyote Creek, by the way–Native AMerican Trickster). And rhythm is one of those ideas I love to think about in front of a picture, though I virtually never think to think about it when making pictures.

Now to the mind-reading:

1. Starting yesterday, and through tomorrow, I’ve been talking with conceptual artist Jonathon Keats, who is in residence at the University here for a project to “give voice” to a stream flowing through campus by placing rocks so as to produce a rondo-structured musical composition for observers walking along the creek. (See the brief description on Art Bozeman; I’ll doubtless have more later.)

2. Just this morning I was thinking I need to find time again for my guitar practice. I had started up again over the holidays, emphasizing the flamenco pieces I’d studied, including tango.

3. The photograph you chose to show, of white water amid a dark wood, is a great lead-in by contrast to my upcoming post, about a mini-study of a stream I snowshoed up two days ago, tentatively titled Black Water.

David,

I always felt, looking at your American Dreams paintings, that there was a mysterious story behind each. It was fun to try to imagine what it might be. Very interesting to hear that owes something to the Beatles.

There are no “unrelated” disciplines.

This reminds me, though, of Steve’s very recent question — are artists interested in science? Perhaps a more fundamental question is how did these things get separated in the first place? What is this weird (I think it’s weird, and not in a quaint way) compulsion toward ever tinier and more impermeable specialization of interest and endeavor?

Of course there is value in delving deeply into one thing or a group of closely related thigns — but must that mean absolute ignorance of every other thing? Sheesh.

Karl:

Well hello!

Steve’s photo is a stunner. I can’t get over the milky stream which either obliged by being foamy withal, or was loaded with powder from an upstream glacier. Surely a time exposure was involved. And the wooded graveyard that borders it is eloquently jagged and assertive yet subject to the water’s whims. Does this describe anything about the tango as well? Last Tango In Paris was my introduction to the form, so my first impression was rather steamy. But there seems a strong element of thrust and parry in the Tango, of soft and abrupt movements. Steve’s image suggests a history of that kind of thing between the living waters and the now-dead limbs.

Steve:

I wonder what Johnathon Keats thought about during his twenty four hours. That was likely one of the points of the exercise.

Jay: I’ll ask, but I don’t know what sort of answer I’ll get. At the performance/installation Keats kept it conceptually “pure” (though maybe he meant the content of his thoughts) by offering collectors only the stamped time cards (he sat next to a time clock) indicating the time of each thought. Written down, it would no longer be a thought in itself, but a thought about a thought…

I always felt, looking at your American Dreams paintings, that there was a mysterious story behind each. It was fun to try to imagine what it might be. Very interesting to hear that owes something to the Beatles.

The Beatles, and also probably Woody Allen and Gabriel Garcia Marquez. I was looking for a way to use personal expeiences as starting points in creating fictional images that were emotionally engaging and funny at the same time. The Attempts at Flight paintings were based on a combination of childhood experience (jumping off the roof of our house, and going very high on the swingset and letting go), flying dreams, teh Icarus myth, a scene in One Hundred Years of Solitude, Italian Renaissance paintings, and those hilarious old film clips of pre-Wright Brothers attempts to build and test flying machines.

…a project to “give voice” to a stream flowing through campus by placing rocks so as to produce a rondo-structured musical composition…

Robert Irwin did something in the same spirit by placing rocks in the stream at the Getty garden in order to tune the sound of the water flowing…

Of course there is value in delving deeply into one thing or a group of closely related thigns — but must that mean absolute ignorance of every other thing?

It turns out that absolute ignorance can be achieved even without going to the trouble of delving deeply into anything. Check this out:

Verizon Math

Had a big breakthrough in grad school when I realized how the Beatles’ use of fictionalized personal experiences as points of departure could be applied to narrative in paintings.

David,

This is very interesting to me. Last year I wrote a long first draft of a sort of novel (for my own pleasure only) and I also found (even though I had been told by others, it was a big surprise to experience it myself) that fiction provided an excellent way to express personal experience, perhaps better than non-fiction. It was not an auto-biographical novel, in the sense that I mapped onto one of the characters directly, which perhaps made it even more surprising.

Karl, I think art gives us the opportunity to create and experience a sort of heightened reality.

Actual life experience is a great source (I’ve heard of writers riding buses or sitting in cafes eavesdropping, in order to capture convincing dialog). I think in art (including stories) there is the chance to use “real life” as a raw material to create something even more real (in the sense that it shows some underlying truth or essence of the human condition.

Steve:

And nobody asks what the nude in the corner is thinking?

David:

The Getty came to my mind as well. Perhaps Keats was thinking about that Beatles song that goes “I saw her standing there”.

rhythm is one of those ideas I love to think about in front of a picture, though I virtually never think to think about it when making pictures.

Steve,

Painting or drawing let’s me get into rhythm explicitly more than photography, simply because it’s hard to miss the rhythm in the process itself. I suspect we do respond subconsciously to rhythm when making photos as well (if we are being selective). What I got from this post, in part, was to ask myself, how much more can I be aware of the various levels in the images I make?

Melaine,

Since I’ve been studying the cello this last year, I’ve gotten in contact with lots of ‘classical’ musicians. What amazes me is that very few classical musicians compose actively (in the sense of composing at something approaching the level and intensity with which they perform other people’s work). I think nearly all of the great composers of the past were also great musicians (Bach was primarily famous for his performance rather than his music itself in his day, for example).

I tinkered with composing at a simple level and I found that it VASTLY increased my awareness of what I could do with the instrument. It was also great fun. I would bet that if the famous soloists of today were also actively composing and performing their work, we would have a lot more valuable ‘classical’ music (I use that term simply to mean music performed on classical types of instruments).

So as you say, Sheesh!

But there seems a strong element of thrust and parry in the Tango, of soft and abrupt movements.

Jay,

There are two different sorts of tango. One is social tango (the video I linked to and the web site are devoted to this). This could fairly be called “real tango” or at least, “original tango.” Like all social dances, the primary focus is your partner, whom you hold in a fairly close embrace. “Stage tango” is something different, this is tango performed for the explicit enjoyment of an audience. This latter type is what most people associate with tango, it fits the description you gave above. It is, as I see it, a kind of external representation of the inner feelings of people doing social tango, a kind of a picture of “tango feelings” through dance. For my taste it is a bit too stylized and formalized. Social tango is at its essence improvisational, reacting on the spur of the moment to the flow of the music and the people on the dance-floor.

The two forms tend to get confused and merged outside of the land of origin.

Karl,

I think one of the reasons that classical musicians rarely compose, is that performers (and conductors) are generally evaluated on the basis of how accurately they execute what’s supposedly in the score. It’s about “getting it right”, rather than thinking creatively. Contrast this w/ jazz or rock musicians, who are appreciated for their improvisational skills (most of them also compose music).

The visual equivalent, I suppose, would be rewarding artists based on how well they could paint the Mona LIsa. Not that it would be easy (!), but we’d end up w/ a huge surplus of Mona Lisas :-)

I think in art (including stories) there is the chance to use “real life” as a raw material to create something even more real (in the sense that it shows some underlying truth or essence of the human condition.

. . . Or maybe, it simply helps us to make up more whopping lies than we could do in a vacuum.

But seriously, David, yes, I agree! It was amazing to me how easy it was to make a mosaic out of different memories, each piece coming to hand at the moment I needed it. What could explain this? I think the idea that there is an larger underlying truth — that guides the flow of thought and allows memories to organize creatively — is compelling.

. . . Or maybe, it simply helps us to make up more whopping lies than we could do in a vacuum.

Karl, I know you mean this as a joke, but you’ve really hit upon something. How often have you heard about some real event that was so absurd that nobody would think of making it up because it wouldn’t feel believable?

David,

Here in Holland it’s getting late, but I will be thinking about your comments!

Karl, it’s good to have you back! I missed you. I’ve been out of the loop at A&P for awhile too, but it looks like I picked the right day to check back in :-)

About guitar playing, I just read in Daniel Levitin’s ‘this is your brain on music’:

“Joni (Mitchell)’s genius is that she creates cords that are ambiguous, chords that could have two or more different roots. When there is no bass playing along with her guitar (as in “Chelsea Morning” or “Sweet Bird”), the listener is left in a state of expansive aesthetic possibilities. “

Birgit,

That’s a terrific quote, and fits with things we’ve discussed in the past about ambiguity. Along with flamenco, my favorite style is jazz, and I enjoy the odd sound you get when you put jazz chords into a flamenco piece.

[the] listener is left in a state of expansive aesthetic possibilities

Birgit,

feel that way about silence.

we’ve discussed in the past about ambiguity

Steve,

Ambiguity, sometimes I think it’s good, sometimes I’m not so sure. How much ambiguity in art is simply a way of hoping the viewer will come up with some kind of understanding that escaped the artist?

David,

Chatting with you in the comments yesterday, I felt like I was transported all the way back to (let me check…) October 2006. Which is thought provoking. Well, I’m glad you came by, that is an encouragement to get started on another post . . .

How often have you heard about some real event that was so absurd that nobody would think of making it up because it wouldn’t feel believable?

I think the entire Bush administration fits this mold. As fiction, it would seem lame on the part of the author. Obama would make better fiction, I guess.

Silence, emptiness!

Once, after Itzak Perlman played a short piece from Berg, he told the audience that he would play the piece again and now we should listen to the silent space between the notes.

Miles Davis, according to Levitin, also ‘described the most important part of his solos as the empty space between the notes, the “air” that he placed between one note and the next.’

Levitin continues saying that likewise, Picasso ‘described his use of the canvas: The most critical aspect of the work is not the object itself but the space between objects.’

Jonathon Keats, the conceptual artist mentioned in comment #2, offers a silent ringtone for your cell phone, a remix of John Cage’s 4’33”. Read about it on Wired.

Karl,

I will be reading and rereading this — I just finally remembered “Hernando’s Hideaway” — a tango tune from my youth, which keyed me into the rhythms that you have illustrated. I need to think about rhythms and my own work (of course, duh, it’s all about me, right?)

The comments are also worth pondering. D — at the Goldwell Open Air Museum that I wrote of is a wood carving called Icara (see my post from a couple of weeks ago). It’s a take-off of Icarus, but the poor, well-endowed creature is stuck up on a couple of telephone poles with her arms/wings in a most uncomfortable looking position.

So in a recent painting (Draft 3 in my residency journal) I have freed her. She really is more comfortable flying, even if she crashes.

Welcome back, Karl. Your observation about writing seems exactly like my thought about painting — sometimes I paint so I can look and look again and then again.