Some of you already know that I’ve been copying Emily Carr paintings for the last week or so, attempting to understand more fully how she does forests and trees.

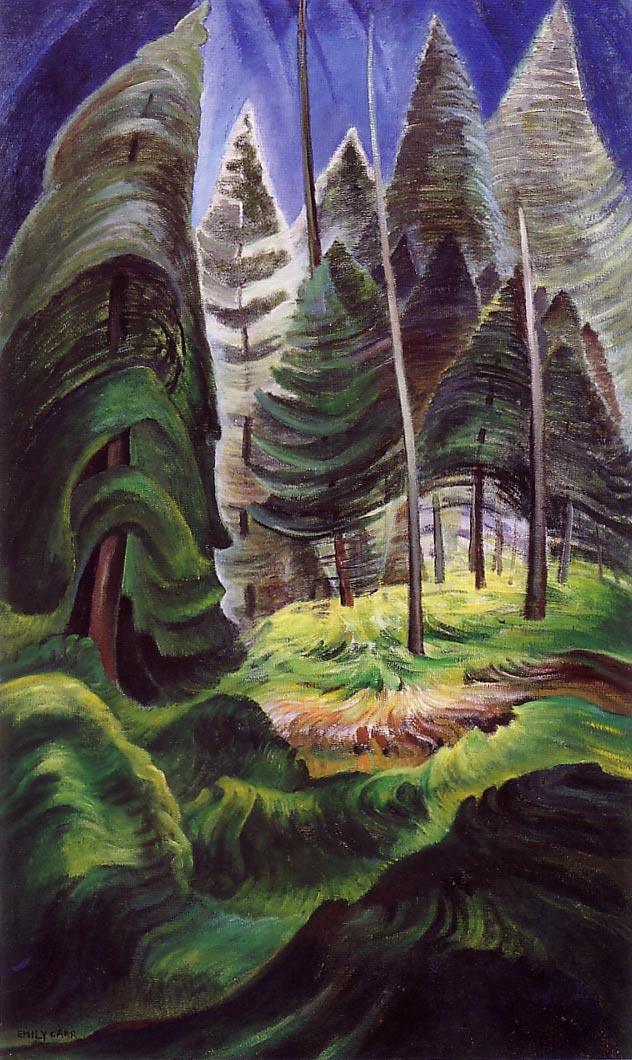

Emily Carr, Cedar Sanctuary, 38 x 26″, Oil on paper, 1942

I’ve learned a lot through this exercise [ including the rule that I must paint-over or otherwise destroy the copies I’ve made before someone comes into the studio and exclaims with pleasure over them. Such an exclamation forces me to admit that what the complimenter is seeing is a copy, causing embarassment all round.] Carr’s finding of shapes in the complexity, of making color within the shapes, and of “draping” her branches are all valuable for my own art-making thoughts.

However, during this process, I had other kinds of questions occur.

I claim to be a painter of places. These are very specific places, although I can lump them into categories: wonky city-and-hamlet scapes, tree-scapes, desert-scapes, genteel fields-and-tree landscapes. But I really think of them as moments in time, when a particular place at a particular time catches me at a particular place and particular time and we interact.

My painting is not about the picture plane of the canvas, although it obviously deals with that. It’s not about technique although I’m studying hard Carr’s technique. It’s not about color or shape or concept. It’s not even about me, although I occupy some corner of its being. It’s about place/space and my sense of the place/space interlaced with one single moment in time. What I hope to evoke for others is a sense of a particular place, time, and vision.

Underwood, The High Note, Basin, Montana, Oil on canvas, about 20 x 20, 2008

The question that this brings up is fairly fundamental. It has to do with a notion about style or “voice” — the idea that a mature artist has evolved a particular style that is recognizable over a range of subjects. An artist’s voice is what collectors look for, what curators need for exhibits. It’s part and parcel of an American sense of self, individualized, particularized, not like anyone else but instantly identifiable. In that sense, finding one’s voice is all about “me.”

Of course, the general construct of style turns out to be flexible. You only have to think about the changes in styles of dress or changes in ways of behavior when you move from place to place, even in the homogenous USA. When I was in Kansas, I almost never wore blue jeans. In Wyoming and Oregon, I almost never wear anything else. The time you arrive for dinner is highly dependent upon whether you were in New York City, Laramie Wyoming, Slate Run, Pennsylvania, or Portland Oregon. And if you have friends from different places, sometimes it’s best to spell out what “casual” means on the invites.

So is it likely that an artist interested in place would have the same style when addressing the gentle breezes and pleasant sunniness of the Willamette Valley as when painting the February space of the Nevada desert?

Underwood, Oak Island on Sauvies‘, 18 x 24″, Oil on board, 2009

Underwood, Amargosa Playa 3, Oil on board, 18 x 24″, 2009

Or when the remnants of the once rain forest loom overhead on an unprecedentedly hot day in an urban park:

Underwood, Cedars, Mt. Tabor Park, 18 x 24, Oil on board, 2009

Or in the studio, painting a composite of experiences garnered while painting plein air on downtown streets?

Underwood, Circling Traffic, Oil on canvas, about 30 x 36″ 2008

I’m not sure there is an answer to the question of whether an artist’s style should (or will) override or absolutely inform her sense of place, particularly if a sense of immediate place, time, and self is her primary concern. I’m aware that certain elements of the way I paint may appear regardless of the place and time. I’m also aware that while I may be a mature woman, it might be said that I am not a mature painter. Or even that our notions of “maturity” in painting is determined by the ways paintings are given to us — edited to make particular points in books and exhibits, so the art appears consistent throughout when, in actuality, in the painter’s studio, it was far more varied and chaotic. So perhaps the question is a moot one.

But it was brought to me in an immediate way when I moved from copying Emily Carr (brought on by a week of painting trees in an a very “treed” urban park) to a painting I’ve been working on since March, when I was in the Nevada desert. Here’s the desert painting as it appeared prior to copying Carr:

Underwood, The Amargosa Playa 2, draft 2, oil on canvas, about 48 x 50, oil on canvas, 2009

And here it is after Carr:

Underwood, The Amargosa Playa 2, draft 5, still unfinished, about 48 x 50, oil on canvas, 2009

And here’s a Carr painting with some of the technical aspects that this desert Amargosa Playa 2 is playing with:

Emily Carr Rushing Sea of Undergrowth, 1932-’35, Oil on canvas, 44 x 27″

I originally thought this post was to be about the Sublime, that concept that A&P gave me insights into a few years back, when it was the topic of some excellent posts (I couldn’t find the posts to refer back to those posts but I remember being impressed by them). I think that Carr’s forests — and my sense of the forest and the desert — is close to Edmund Burke’s:

Beauty may be accentuated by light, but either intense light or darkness (the absence of light) is sublime to the degree that it can obliterate the sight of an object. The imagination is moved to awe and instilled with a degree of horror by what is “dark, uncertain, and confused.” While the relationship of the sublime and the beautiful is one of mutual exclusiveness, either one can produce pleasure. The sublime may inspire horror, but one receives pleasure in knowing that the perception is a fiction.

(quoted from Wikipedia, The Sublime)

So I am transferring something of Carr’s techniques to my painting of the desert, but I’m timid about that sense of light and darkness as Burke describes it.

I’m not sure Carr’s technique and vision works with a desert painting. I’m not sure it should work. The Amargosa painting may now (or finally) work fine as a vision on the wall, but not as an evocation of time/place/me. And that’s what led me to my current question about style and voice: is it possible to evoke a sense of place and time with techniques from another place and time? Can a person channeling Emily Carr make any headway painting the desert? Anyone want to take a crack at this?

PS: More about the Sublime from Wikipedia:

In his Critique of Judgment (1790) , Kant investigates the sublime, stating “We call that sublime which is absolutely great”. He distinguishes between the “remarkable differences” of the Beautiful and the Sublime, noting that beauty “is connected with the form of the object”, having “boundaries”, while the sublime “is to be found in a formless object”, represented by a “boundlessness”

In order to clarify the concept of the feeling of the sublime, Schopenhauer listed examples of its transition from the beautiful to the most sublime. This can be found in the first volume of his The World as Will and Representation,

For him, the feeling of the beautiful is pleasure in simply seeing a benign object. The feeling of the sublime, however, is pleasure in seeing an overpowering or vast malignant object of great magnitude, one that could destroy the observer.

-

- Feeling of Beauty – Light is reflected off a flower. (Pleasure from a mere perception of an object that cannot hurt observer).

- Weakest Feeling of Sublime – Light reflected off stones. (Pleasure from beholding objects that pose no threat, yet themselves are devoid of life).

- Weaker Feeling of Sublime – Endless desert with no movement. (Pleasure from seeing objects that could not sustain the life of the observer).

- Sublime – Turbulent Nature. (Pleasure from perceiving objects that threaten to hurt or destroy observer).

- Full Feeling of Sublime – Overpowering turbulent Nature. (Pleasure from beholding very violent, destructive objects).

- Fullest Feeling of Sublime – Immensity of Universe’s extent or duration. (Pleasure from knowledge of observer’s nothingness and oneness with Nature). All indented quotes from Wikipedia, “The Sublime.”

June,

I looked up about the Kant’s comment on the sublime and beautiful on Wikipedia, Deutschland, to capture its spirit in his native language. As you mention, first, the idea of boundlessness versus form with boundary. Second, quality versus quantity; third, the advancement of life versus the initial inhibition of life and the subsequent outpouring of life; fourth with respect to character, playful versus serious, fifth, solely (?) in form and perception versus requiring a certain emotional state.

Thanks for introducing me to Kant’s Critique of Judgment . It now clearer to me why I like the Sleeping Bear Dunes. They can be terrifying.

I don’t really understand about Emily Carr yet.

June,

This is very inspirational, thinking about the outlining of boundaries. You introduced Emily Carr and Karl emailed me about de Chirico, both surrealistic in their approach. Both of these painters outline their objects, am I right?- de Chirico in black and Emily Carr in black or in a light color. [Earlier this year, I studied how Janet Fish outlines objects in white looking at one of her paintings in the MSU art museum. On my yellow canoe picture, I played some with outlining in white.] Until yesterday, I had thought that doing the outlining of objects in black would make the painting too heavy, thinking of Braque. But then, Karl emailed me a Botticelli, totally revising my thinking about the power of outlining in black.

After this longish rambling preamble, I want to comment on your Amargosa Playa paintings. In your AP 3, you painted the wide-open space in a misty sort of way, without indicating boundaries between the foreground and the mountains in the background. Likewise, in your AP2, draft 2, the upper aspect of your painting invites me into an indistinct mystery sort of space. In your AP2, draft 5, the boundaries have become more distinct. There is greater definition and less dreaminess.

Now back to Kant’s comment that the beautiful is surrounded by boundaries whereas the sublime has no boundaries and may instill something akin fear. My question is why do the some of the surrealistic pictures by Emily Carr and de Chirico inspire awe, perhaps tinged with a slight degree of fear? Is Kant wrong and the sublime does have boundaries?

Birgit,

I’m still working on your first comment and the Kant translation; the original in German seems very different from Wikipedia’s (presumed) translation. I have to muddle around both sets to see if I’m comprehending.

However, you are correct about the edges. I have been taught, if “taught” is the correct word, by my mostly plein air companions that edges should be “soft” or blurred. In fact, I remember one of my instructors look of shock when it was pointed out that Cezanne sometimes drew a sharp black edge around or across something he wanted to separate out.

I assumed that the blurred edge is in part to provide a separation of painting and commercial design, where clarity is extremely important. Even cameras provide a sharper edge in general than do painters (generally speaking).

Perhaps (to go back to the by-now overworked idea of binocular vision), the binocular vision creates blurs that we generally ignore but which in truth are what we are seeing. So plein air, which directly addresses what’s being viewed (as opposed to studio, which manipulates for the picture plane impact) would be more likely to have blurred edges.

This does not address your question about Kant, the Sublime, and boundaries. Nor mine, about Carr, Kant, and the desert. Conundrums, conundrums.

Perhaps the difference lies in the subjective nature of “dreaminess.” Some of us day-dream positively, some negatively. Some love the potential of limitless space, some dislike it.

When I was on-site, the space spoke volumes of breath to me. I wanted to capture that ability to breathe deeply, limitlessly. Back in the studio, I became aware of a kind of blurriness, a lack of resolution, to AP draft 2, so as I worked with Carr, I “tightened” it. I think I like draft 5 better as a painting (particularly now as it is draft 6, even more tight) but less as being the desert as I experienced it — of that time, of that place.

I have not resolved the conundrums and you have added depth to my thinking. The irresolution, alas, remains. We will be going to the Oregon desert next week, where, perhaps, I will find an answer — or six (we’re to bring at least six supports on which to paint).

And, your Sleeping Dunes is quite stark, having a grand clarity about it. Nothing blurred there. And yet you sometimes find them terrifying. More conundrums.

Here’s a Mary Oliver poem from today’s Writer’s Almanac http://writersalmanac.publicradio.org/

that captures, somehow, what I think I am doing: “tomorrow” here becomes a metaphor for the desert, and my “dreaminess” about it.

Walking to Oak-Head Pond, and Thinking of the Ponds I Will Visit in the Next Days and Weeks

by Mary Oliver

What is so utterly invisible

as tomorrow?

Not love,

not the wind,

not the inside of stone.

Not anything.

And yet, how often I’m fooled-

I’m wading along

in the sunlight-

and I’m sure I can see the fields and the ponds shining

days ahead-

I can see the light spilling

like a shower of meteors

into next week’s trees,

and I plan to be there soon-

and, so far, I am

just that lucky,

my legs splashing

over the edge of darkness,

my heart on fire.

I don’t know where

such certainty comes from-

the brave flesh

or the theater of the mind-

but if I had to guess

I would say that only

what the soul is supposed to be

could send us forth

with such cheer

as even the leaf must wear

as it unfurls

its fragrant body, and shines

against the hard possibility of stoppage-

which, day after day,

before such brisk, corpuscular belief,

shudders, and gives way.

“Walking to Oak-Head Pond, and Thinking of the Ponds I Will Visit in the Next Days and Weeks” by Mary Oliver, from What Do We Know. © Perseus Books Group, 2001.

…I would say that only

what the soul is supposed to be

could send us forth…

June,

Your paintings are so wonderful. I love your colors and brushstrokes.

I remember learning about Emily Carr in a women artists class, her work always brings me a sense of balance.

Thanks, Tree,

Given your moniker, it seems appropriate that you should love Carr’s work; she clearly loved Trees.

Soon I may be somewhere where I can paint ponderosa pines. I’ve tried these before without success — and they aren’t coastal plants, so Carr never encountered them paintbrush in hand. It will be interesting to see if I can manage to make them as exciting as Carr made the Cedars.