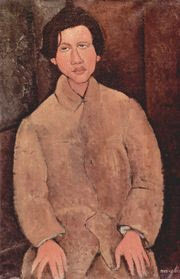

Modigliani, Portrait of Soutine

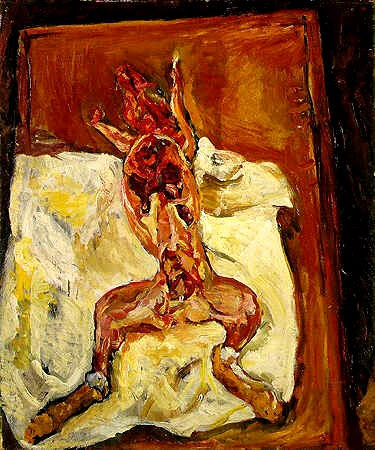

The artist Chaim Soutine’s still life paintings of animals, what I prefer to call his carcass paintings, can be unsettling, especially given the fact that Soutine was known to have never worked from memory, but rather used live, or dead, models for all his works.

Nearly all of Soutine’s art can be jarring to the viewer for a variety of reasons; his use of color, his lines, his brushstrokes and overall style as well as his subject matter are startling, but after our initial response what are we to make of these works? And what is it that Soutine was trying to say?

The bulk of Soutine’s carcass paintings cover a span of ten years, from 1916 to early 1927, as well as a couple of works completed around 1933, and include depictions of fish, rabbits and various fowl. They increase in their intensity and graphic content by the early 1920s before leveling off again to a calmer style.

In the scholarship on Soutine, much has been made of his use of food imagery in his still-life paintings. I’ve learned that his many years of poverty and continual stomach illness often made food unattainable; so with that in mind it makes perfect sense to have forks jutting out like arms from a plate of fish, as in an early example, Still Life with Herrings, from 1916. In addition to this, the traditions of his Jewish religion and culture relied heavily on food rituals.

Still Life with Herrings, 1916

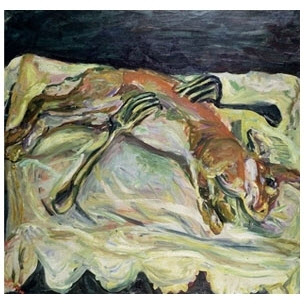

The 1924 painting, Hare with Forks, also depicts a dead animal with forks on either side like a pair of arms reaching in to grab the flesh, while the more visceral Flayed Rabbit from 1921 depicts the animal without forks; yet both animals lie on white cloths like sacrificial martyrs, leading one to the conclusion that there is a greater unifying theme besides food issues to the series of works.

Referring to the Christian imagery commonly used in Medieval and Renaissance paintings sheds an interesting light on how the animals in both of these paintings are carefully posed; the flayed rabbit is in the crucified position or possibly as a St. Sebastian, tied to a tree and awaiting the many arrows. And the fact that the one rabbit is flayed points to the fate of more than one saint and also most famously the painting by Titian, The Flaying of Marsyas. Yet there is still a sense of defiance in the upraised arms and stretched legs.

Flayed Rabbit, 1924, Barnes Collection

The Flaying of Marsyas, Titian 1570s

In Hare with Forks, the hare lies on its side slightly curved like a fetus, with fur intact and two forks resting gently on either side of its narrow torso; while a sense of heartbreak permeates, there is little sense of violence in this painting, rather the hare looks like it is asleep, but one understands it is still a sacrifice. It should also be noted that according to Jewish dietary law, rabbits are treyf, or forbidden, food and further, the word treyf is not only used to describe forbidden food but also a bad person.

Hare with Forks, 1924

Where did these ideas come from? In my research I learned that Soutine adored the Old Masters, Rembrandt in particular, and reworked many of their paintings in his own style. So in this respect it isn’t that unusual to think he would use the imagery of the martyrs that he studied in painting after painting in the Louvre.

A Woman Bathing, 1654, Rembrandt |

Woman Entering the Water, 1931 |

When reading the stories of those who knew Soutine and who witnessed his intense and at times religiously ecstatic reactions to art it also makes sense that Soutine would incorporate these Christian themes in his works, but what of his Jewishness? One may look at the carcass paintings through the above described lens and think that Soutine, born Chaim Sutin in a shtetl in the Pale of Settlement, would have truly abandoned his Orthodox upbringing as many claimed he did, or as Soutine himself stated.

Self Portrait, Chaim Soutine 1918

And while it is true that Soutine did not practice any form of Judaism in the traditional sense after he left Belarus and moved to Paris, it is my belief that he did continue to practice his own form of the religion, with his artistic process taking on the form of religious ritual and metaphysical exploration and all the while a tug-of-war taking place between an outright defiance and embrace of Judaism and its laws.

Tree,

These are almost the opposite of the June’s expansive landscapes. About the only subject of Soutine’s besides dead animals that I’ve come across in browsing the web is flowers, a seemingly very different choice. I found nary a portrait or landscape–do you know of any? He was evidently not an outdoor person; I imagine him working in his dim rooms, not even a separate studio.

The forks are curious, especially in their placement, which does not fit a meal setting, either a set table or in the midst of eating. That suggests a kind of ritualistic or allegorical meaning, or a reference to the human who has determined the fate of these animals.

Tree,

Thank you for bringing Chaim Soutine to my attention. I love his magnificent use of color as, for example, the reds/yellows in Les maisons rouges. c. 1917 or the yellow/green/blue in Deux enfants sur la route. c. 1939 and the occasional wondrous blues.

In terms of shock value, I cannot bear looking at Titian’s painting. Considering skin a beautiful organ and having dedicated much of my life to learn about its sensory innervation, flaying of live humans strikes me as an abominable torture. In contrast, skinning of dead animals, I take as a normal procedure having visited slaughter yards as a child. Not being much into religious symbolism, I am more excited over the striking juxtaposition of red and yellow hues in the flayed rabbit than over the subject matter.

It is not surprising that his skinned animals commanded much attention because of the novelty of the subject. It excites a sense for the macabre as evidenced by Roald Dahl short story skin.

Birgit,

Thanks for showing up my too hasty research. Somehow I got on a site with over 100 Soutines, almost entirely animals or flowers. It looks like he did indeed paint in other genres throughout his career. Les maisons rouges looks quite placid compared to the reeling distortion of Cagnes landscape with tree or The road up the hill. The two children in Deux enfants sur la route seem not to notice the landscape buckling up behind them. Reminds me of van Gogh and Munch.

Steve, Soutine did a great many portraits. A well known example is The Little Pastry Chef. He also generated a large output of landscapes, particularly landscapes of Ceret, France. However, he hated the works and destroyed many of them. One scholar, whose name escapes me right now, did some great research on Soutine’s unique portrayal of the landscape and in particular his trees, which he compared to the beliefs of the ancient tree worshiping pagan religion that had existed in the area where Soutine was raised.

The last work he ever created was of two children walking down a road, by the way.

I agree with you about Titian’s painting, Birgit. I remember Medieval/Romanesque art history classes where I sat with a queasy stomach studying slides of flayings and other horrible tortures.

As often happens, the copy of Flayed Rabbit posted here doesn’t do the painting justice. The original is really something to see.

Have you seen the gladiolas he painted? You would enjoy the intense reds.

Tree and Steve,

I will be able to see the gladiolas in the Brooklyn museum on a trip to NYC. Seeing the landscapes at the Tate will be more of a challenge.

I do like Soutine’s trees a lot. Associating the way that they are painted with ancient tree worshiping of the pagan religion is interesting. Naively, from my remote position in time, I prefer pagan tree worshipping to Roman Catholic symbolism.

It is touching that the theme of his last paintings were two children walking towards us on a road, holding hands.

Soutine must have been an interesting person – paganism, Christian symbolism/Jewish dietary laws and finally trust and hope.

Looking at these pictures again, I realize that, with the exception of Woman entering the water, they seem quite uncomposed and direct, focused more on the subject matter than the context. Like Soutine just wanted to get down the thing that he saw, and a pleasing balance was of no interest.

In the self-portrait, is the second figure just the back side of a re-used canvas?

Looks that way, Steve. I always assumed it was a canvas but I haven’t studied this work extensively and don’t know if there’s a story to it. It does bring up interesting ideas about double image and such.

I’m wondering if it’s Modigliani, as they were good friends and painted one another’s portraits.

One gets the impression that Soutine had blinders on when painting– he was just so focused on what was in front of him and tuned out everything else around him.

Tree,

Your comments about Soutine and religion seem on the mark in the paintings you’ve posted. Comparing those still lifes with the images that Steve linked to makes me think that your comment: “Soutine had blinders on when painting– he was just so focused on what was in front of him and tuned out everything else around him.”

The forked rabbits (so to speak) pull that focus inward to some kind of metaphysical feeling or meaning, so that the outward “reeling” trees that one painting shows becomes the inward reeling sense of religious horror — or honor — of the other. I can’t help but sense the intensity of the painter — like Van Gogh or a slightly deranged Cezanne — but the meaning of the intensity resides within the artist and is only somewhat able to be understood by the viewer.

Thanks for this view of Soutine. It’s been a long time since I looked at or thought much about his painting. I am interested, as perhaps are Birgit and Steve, in the intensity of the experience of the artist which becomes manifest but not necessarily explained, in the work. I think Birgit’s Lake Views in “Sand Painting” are a partial result of her continued experiences of that view. I am eagerly awaiting the results of that clearly intense experience.

Soutine’s carcasses, especially of large animals are spiritual — great suffering when the insides have been exposed,the bones crushed, bleeding and twisted almost beyond recognition- express life and it’s aftermath — there is no joy in these paintings, but great beauty.In hindsight – I look at it and see the Jewish Crucifixion

Michal,

That’s a very interesting and profound observation. Thank you.

I think you might be interested in an article I wrote about a contemporary artist named Jennifer McRorie – http://page51.ca/jenn-mcrories-passion/