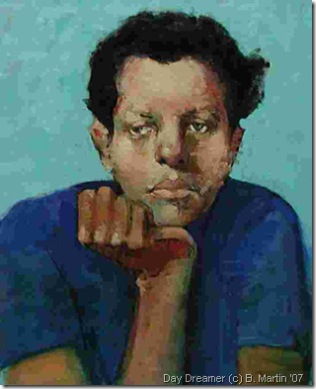

This is the end product of a demo I posted on another site. The process I used was to do a series of acrylic washes until I thought I knew the person I was looking for in this painting. Then started to build in oil, leaving some of the acrylic visible. I kept from moving away from my original idea by avoiding the urge to make everything perfect. I thought about making the hand smaller or detailing the neck line of his T-Shirt, but it remained just a thought. I had the feeling that I was done and it was time to move on to something new.

This is the end product of a demo I posted on another site. The process I used was to do a series of acrylic washes until I thought I knew the person I was looking for in this painting. Then started to build in oil, leaving some of the acrylic visible. I kept from moving away from my original idea by avoiding the urge to make everything perfect. I thought about making the hand smaller or detailing the neck line of his T-Shirt, but it remained just a thought. I had the feeling that I was done and it was time to move on to something new.

Archives for art world

How I Stop and Start Something New

Knowing when to take a break from art

Sunil‘s post Art, life: Separate or unified? raised the issue of whether an artist should try to be an artist all of the time. I commented that doing art requires intense observation and sensitivity — which is obvious. What is less obvious is that observation coupled with sensitivity are another way of saying “emotional reactivity.” That is, an insignificant input — the curve of a leaf — can cause a disproportionately large emotional output (that looks beautiful!!!!!) which, coupled with the act of painting, allows the artist to make the brushstroke that the moment requires.

Emotional reactivity is essential for making art, but out of the art-making process, it can be annoying, disruptive, counter-productive. The soldier and the policeman are trained not to have emotional reactivity, but the artist needs to develop it, harness it. The challenge for the artist it to be able to switch it on and off at the right moments.

There are the simply structural solutions for getting out of the art mode: don’t go to the studio on off-days, turn the pictures to the wall. The psychological solutions are more subtle: don’t think about that difficult painting or series at the wrong moments.

What do you do to take a break from art? Is it easier to get into “art mode” or to get out of it?

Art, life: Separate or unified?

I had the good fortune to go to a very good group show at the MoMA recently with the provocative title ‘What is painting?’. One among the many works that I ran into was by a lady artist of the 1970’s Lee Lozano. Not having studied at art school, I did not know much about her (well, I did later find out that she really is not a household name) until I came back home and read up a little bit about her. The more I read, the more I was fascinated by how she had managed to integrate art and life into a seamless whole. From reading, I surmised that her desire for painting went beyond the confines of the canvas and she tried through her art/life to incorporate the viewer and her life in a strange union.

The NeoIntegrity manifesto: a new movement?

I read yesterday in the New York Times about a show called “NeoIntegrity” at the Derek Eller Gallery, curated by the painter Keith Mayerson. What caught my eye was the charming manifesto Mayerson created for the show (not included in the article). It touches on many points often discussed here on A&P (but apparently still not settled!). Here’s the manifesto:

Half-finished, deleted, revised, and reviled

I was struck by Sunil’s post about his alteration/destruction of work into which he had put so much effort. In fact, I liked his revised “Palimpsest” very much, although I can see that it doesn’t resemble much of what he has shown us before this.

Because I have so many failed, partly completed, destroyed, altered, and despised pieces sitting around in boxes, baskets, photos and my memory, I thought I’d run through a taxonomy of my bad work and its place in my art-making universe. Ultimately my question is whether I’ve made adequate categories of “failure” or if there are others that could be added; in addition, I wonder if you can suss out what “runs” your failures — what, particularly if it’s not just a problem of quality, causes you to throw up your hands and ditch work.

So here are my categories. There’s work that simply fails — period, full stop. There’s work that gets altered, thus morphing into something else. There are series that come to an abrupt halt. And finally there’s work that’s put on hold.

Failed work has its own subcategories, of course, including failures to work the materials, failures of skill, failures of insight, and failures of resonances within one’s conceptual worlds. more… »

The paradox of non-distracting distractions

Mark Hobson: Art-making . . . I ‘think’ about nothing when I am in the moment of picturing. . . Don’t think about it now, just picture it ‘intuitively’.

Birgit posted this from Cezanne: “…if I think while painting, if I intervene, why then everything is gone.”

Hobson and Cezanne are both essentially saying: verbal thought, stay out of the art.

The surprise to me is that highly distracting stimuli — the guys working in the café kitchen next door, the book on tape, can disturb me and leave me un-distracted at the same time. My impression from my own experience and what I have read in the comments of the previous posts is that the non-verbal artist “within” for the most part doesn’t care what kind of distracting words are passing through the mind, as long as they don’t interfere with the art-making.

Cogito ergo sum

When we ask the question, “What do you think about when making art?” the real question is: “When we say ‘you’, to whom are we referring?” They guy/gal inside with all the words thinks he or she is in charge, but the real action goes on separately despite the jabbering.

A bit spooky, no? Because, if you think about it, all that art-making doesn’t just happen. There must be a huge amount of judgement, information processing — thought in essence — without words or access to words. The only way to appreciate consciously/verbally what is going on is, as Hobson says, to ‘listen’, listen to the feelings the work evokes. Not that that’s either easy (with all that distraction) or necessary. Better to stay out of it, Cezanne seems to say.

How to make use of that unnecessary verbal thought while working?

What do you think about when making art? Part II

What to think about when making art? Last week’s post brought some valuable insights. First, Jay helped to refine the question. “Depends upon where in the project you are,” he wrote. “If you’re making aesthetic and structural decisions, then you will concentrate on the task at hand.” Steve agreed that there are different stages of work, adding that he finds satisfaction “in consciously working out ‘problems'” in making art. more… »