Posted by Karl Zipser on July 22nd, 2007

Art can take a lot of time to make. What should one occupy one’s mind with during that time? Does an artist need to think about each brush stroke? Or does the creation of art become intuitive?

If art making becomes intuitive rather than thought-based — and to me that sounds appealing — what should become of word-based thought when one is working? Is it better to think about something else, to distract oneself with music, a book on CD?

This is something I’ve been thinking about while painting. What do you think about?

Posted by Sunil Gangadharan on July 5th, 2007

Under the catchwords of accessibility and inclusiveness, a lot of artifacts in the art world are losing its original meaning and interpretations thereof. Simply put: We inhabit a culture of simplification and generalization with the hopes that unpretentious agendas would be understood and assimilated by a larger audience. This has been documented extensively in other fields and is now seen to be creeping into the arts as well. Two examples from either sides of the Atlantic would further illustrate my point. more… »

Posted by Karl Zipser on July 2nd, 2007

Painting

From Life vs.

From Photos

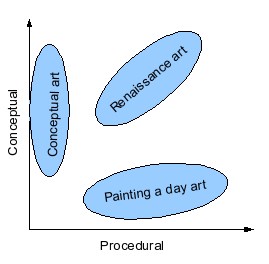

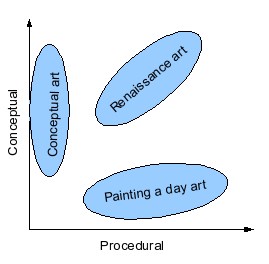

In my previous post I discussed conceptual- versus procedural-based art and asked how an artist could have the two dimensions interact. This got me thinking about how different art forms mix these aspects. Contemporary conceptual art, for example, tends to be big on ideas and light on craft, whereas something like the Painting a Day movement is more procedure-based. Renaissance art, in contrast, combined conceptual and procedural components.

Below I try to express this distinction in a two-dimensional plot where the axes are Conceptual and Procedural.

Note, nothing about this hypothetical representation says anything about the quality of the artwork. It is possible to have a technically developed artwork, full of ideas, that is just plain bad. Conversely, a simple, non-conceptual painting could be something wonderful.

Where on this graph would you like your work to be? Where do you think you are now?

Where is the money today? It seems that the conceptual gets rewarded more than the procedural.

Posted by Karl Zipser on June 30th, 2007

Painting

From Life vs.

From Photos

Jeffrey Augustine Songco recently posted about different modes of art making. [UPDATE, Jeffrey kindly pointed out (comment 3) that some of the points I make about his work are oversimplifications]

He divides his art into two types, which I’ll call x and y. I use these neutral names because the names that Jeffrey used, although descriptive, are somewhat distracting for the point I want to make here.

Art type x “is thoroughly planned (at least as much as I can) and must specificaly state the meaning that I am ultimately trying to convey,” Jeffrey says. He almost never displays art type x in his studio on a normal day. It is what someone else would hang up and call art, but he prefers to look at type y.

With art type y, Jeffrey says “I find myself getting lost in during its creation. It is something that has no specific goal other than to explore my mind creativity.” This type of art is what Jeffrey would (and does) display for himself, and calls art.

Thus, art type x is “concept first” art. It is focused on an idea of what an artwork could be. Art type y is “process first” art. In terms of tangible product, the type y art seems to yield better results — as Jeffrey says, this is what he likes to look at.

Reading about art types x and y in the original post, I wondered, why make art type x at all? Why not simply do type y? I asked Jeffrey this and he replied: more… »

Posted by Karl Zipser on June 25th, 2007

Painting

From Life vs.

From Photos

Mind you, the most perfect steersman that you can have, and the best helm, lie in the triumphal gateway of copying from nature. And this outdoes all other models; and always rely on this with a stout heart, especially as you begin to gain some judgment in draftsmanship. Do not fail, as you go on, to draw something every day, for no matter how little it is it will be well worth while, and will do you a world of good.

—Cennino Cennini, 14th century

Cennino’s statement that studying from nature is the best way to learn to draw is something that resonates today. My question is, what constitutes “copying from nature”? Is drawing from photographs the same as drawing from life? Or is working from photos more like copying the work of another artist? The question is of practical importance, because as Cennino pointed out, studying the work of another artist will influence one’s personal style.

We cannot separate how we see from the way photography has informed our vision.

—Dan Bodner

. . . it is best to remember that every object made by man carries within it the evidence of the time and place of its manufacture.

–Joseph Veach Nobel

If an artist draws from photos, does he or she inevitably absorb the unique “style” of the camera (not to mention the style of the photographer)?

Posted by June Underwood on June 22nd, 2007

It’s interesting to see Sunil lamenting the lack of contemporary portrait artists as I consider my own dilemma — too many landscape artists. Or maybe just too many that follow me into drugstores and gift shops.

How do you respond to the old masters, those artists whose work stuns you and also follows you, ubiquitous, featured on postcards, tea pots, and backsides everywhere you go? This is a question I’ve been pondering.

Recently on the blog I adminster, the Ragged Cloth Cafe, one of the regulars posted a blog on Ansel Adams. My response to her comments was a bit jaded, or maybe even irritated. Another of the regular posters on the blog called me on it: “June, you do sound a bit cranky and a bit unfair to modern landscape photographers. Or is it like seeing drip painting and only being able to think of Pollack?”

As I reread what I had written I realized that indeed I was sounding more than bit cranky (and even a bit incoherent). After a few further comments I sorted out what my head was thumping around with, dissing Adams. Here’s something of what I wrote:

You may have hit on why I am currently in a state of irk-dom about Adams — it’s because I’m trying to find my own way with landscape and his images loom altogether too large in my mind. I have to wrangle and fight with him a bit (Jacob and the angel?) to make my way to my own vision.

I often find this is the case for me — at various times in doing my art, I find myself fighting my way through to my own style, arguing (if only with myself) about the too-much-with-us-giants who block my view.

I think this is yet another version of Karl’s posts here and here) “Why is making art so hard?” I had the same difficulty with the Cubists (see the two homemade oils that flank this post) with whom I spent the last 10 days harrassing and wrestling. Oddly enough, though, I don’t have the same issues with Cezanne. It may be that he is just far enough out of the old masters/coffee-cup loop to give me fresh insights rather than making me strain and struggle to see afresh.

It’s not that I blame the artists for being so outstandingly good (even I admit that that’s a bit over the top); it’s that to see afresh is such a struggle that I want to fling a paint-loaded brush onto my memory book of Adams’ photos and smear them thoroughly so I’m not seeing them while I’m working. It’s a kind of internal thrashing about, trying to break through to the other side.

more… »

Posted by Karl Zipser on June 17th, 2007

Sometime in the 14th century, Cennino Cennini wrote Il Libro dell’Arte as advice for how to be an artist. One of the most interesting passages, I think, is how an artist should go about developing a personal style. Cennini begins:

take pains and pleasure in constantly copying the best things which you can find done by the hand of great masters. And if you are in a place where many good masters have been, so much the better for you.

The point of the exercise is to learn from the source. This means that the choice of master to copy is important. Cennini continues:

But I give you this advice: take care to select the best one every time, and the one who has the greatest reputation. And, as you go on from day to day, it will be against nature if you do not get some grasp of his style and of his spirit.

Selecting the right masters to copy is still not enough. Cennini recognized that the particular interpretations of one artist needed to be studied consistently:

For if you undertake to copy after one master today and after another one tomorrow, you will not acquire the style of one or the other, and you will inevitably, through enthusiasm, become capricious, because each style will be distracting your mind. You will try to work in this man’s way today, and in the other’s tomorrow, and so you will not get either of them right.

By choosing the right artist to study, and by studying his work consistently before studying that of another artist, one will achieve the preconditions for finding a personal style:

If you follow the course of one man through constant practice, your intelligence would have to be crude indeed for you not to get some nourishment from it. Then you will find, if nature has granted your any imagination at all, that you will eventually acquire a style individual to yourself, and it cannot help being good; because your hand and your mind, being always accustomed to gather flowers, would ill know how to pluck thorns.