Posted by Sunil Gangadharan on January 30th, 2008

There is a certain cosmic element about large battles described in epics like the Iliad or the Mahabharata. Maybe the forces unleashed from the large seething masses of humanity numbering in the tens of thousands as they stand to square off in what could be the last day or night in their lives evokes out of control celestial bodies – or maybe it is the magnitude of destruction about to unfold while rational thought remains crucified at the battlefield entrance helplessly watching the bloodletting that ensues… I am not sure, but there is something other worldly about them that pricks our atavistic core. Childhood memories are fairly strong – or so neurologists say – it must be because our brain cells have not fully formed then and any available sliver of information is indelibly singed on our neurons… For some reason, to this day, I remember vicariously participating in the imaginary battles while the warring clans clashed under the overcast demeanor of Kurukshetra through comic books such as the Amar Chitra Katha…

One such scene from this epic tale unfolds with two very large armies about to face off each other over a vast battleground. Moments before the time of reckoning draws near and that first arrow rends the sky, one of the commanders experiences a sudden burst of self-doubt and starts a dialogue with his charioteer on the nature of humanity, the soul, our existence and filial duty. A striking tableau develops when his charioteer drives the chariot out to the midlines of the battle field and starts to explain the answers to some of the questions posed. The interesting exchange between the doubtful commander and his self assured charioteer is so powerful that it forms a separate section of the Mahabharata called the Gita. Though I would consider certain portions of the conversation between the two to be bit facile, a lot of the principles laid out in this conversation that took place thousands of years ago resonates even today.

Even if the words did prod my thinking in many ways, the aspect of the epic that was most retained in my mind from all those surreptitious nights of comic book mythology was the battle. This painting (below) is an attempt at trying to capture some those crucial moments before the impending battle. This scene is a familiar one and numerous Indian homes have a semblance of this tableau in some framed format. Owing to the scale and the gravity of the scene, I decided to try something large scale (though it was not really necessary) – I had not done anything so large before and the aspect of size in and of itself presented its own peculiar problems. Finished, the painting is about nine feet wide and six feet tall. I did make a mess of our basement completing the thing and am not sure how long that is going to take to clean the oil paint mish mash left on the floor. It took about two and a half months for me to go through the motions of the initial measurements, sketches, gesso ground and finally painting the canvas in three sections – the middle first, followed by the left and then the right side.

Sunil Gangadharan, ‘Everyman and the charioteer’, Oil on canvas, 101″ X 73″

Posted by Sunil Gangadharan on January 17th, 2008

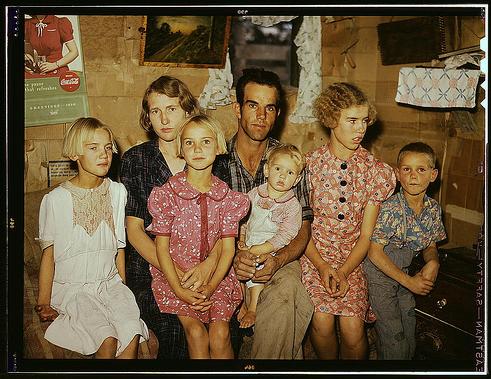

The United States Library of Congress put up thousands of archival pictures from the Great Depression to World War II on Flickr today. A classic collection of photos, they capture in full color an era generally seen and imagined in black-and-white.

The photographs convey a more innocent time when a country did not have to mount multi-million dollar campaigns to elect a president. These photos are in public domain and have no known copyright restrictions. The flickr library here.

Jack Whinery and his family, homesteaders, Pie Town, New Mexico, Sept 1940, Photographed by Russell Lee

Posted by Sunil Gangadharan on January 9th, 2008

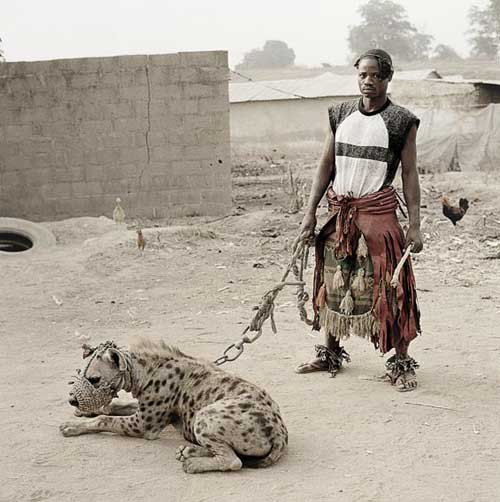

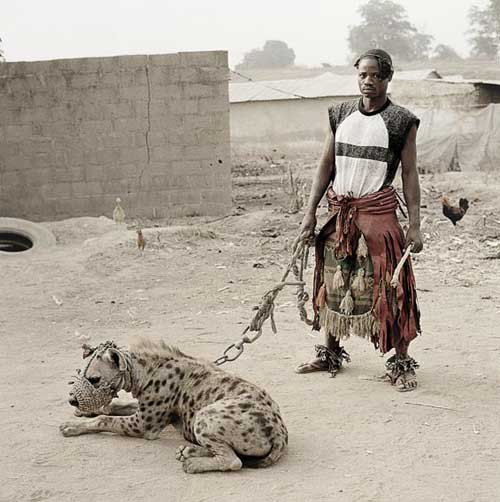

I was over at the Yossi Milo gallery the day before yesterday intending to look at their latest photography exhibit that was getting a lot of press in recent times. The exhibit features the journey of a photographer (Pieter Hugo) to Abuja in Nigeria and his chronicling the lives of an itinerant group who are known as the ‘hyena handlers/guides’ (Gadawan Kura in Hausa).

In Pieter’s own words: more… »

Posted by Sunil Gangadharan on January 3rd, 2008

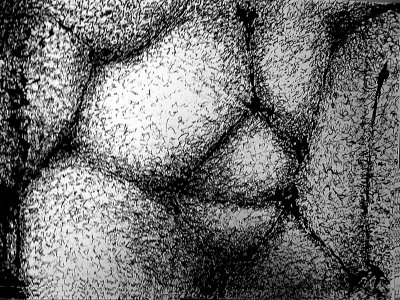

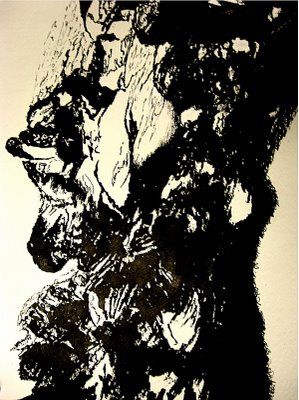

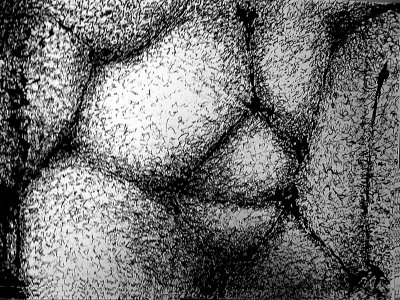

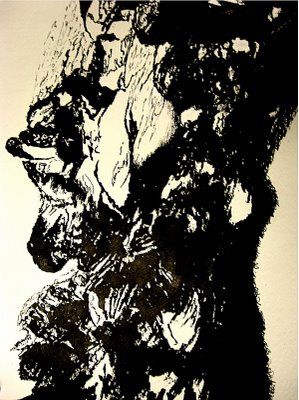

Sunil Gangadharan, ‘The United States of Adipose’, Sumi ink on 400 series watercolor paper, 11″ X 14″

There was not much to write about today. These drawings are some of my recent ones. Nothing serendipitous, (if Steve were curious), but a slow burn and thrill involved in teasing ink using a bamboo pen over the creases and crevices of highly textured paper.

Sunil Gangadharan, ‘Untitled_12_26_07’, 11″ X 14″, Sumi ink on 400 series watercolor paper

Posted by Sunil Gangadharan on December 27th, 2007

Roberta Smith wrote a lively piece in the Sunday Times last week titled ‘What we talk about when we talk about Art’ (link here). She weighed in on the use of commonly used clichés used by the artworld that inherently reflects and harbors intellectual insecurities. As an example, she talks about the oft over-used ‘Referencing‘ (as in the statement “this work referencing male chauvinism uses…”), ‘Privilege’ (as in “privileging the leftist agenda”) and ‘Practice’ (as in “my studio practice”). I have seen these used and sometimes abused in many artist biographies, statements and exhibition descriptions. While Referencing really means ‘referring to’ and Privilege means ‘favoring’, it is the term Practice that has the biggest potential for being misconstrued…

She makes three assertions:

#1. First off, there’s the implication that artists, like lawyers, doctors and dentists, need a license to practice. Many artists already feel the need for a license: It’s called a master of fine arts. But artists don’t need licenses or certificates or permission to do their work. Their job description, if they have one, is to operate outside accepted limits.

#2. Second is the implication that an artist, like a doctor, lawyer or dentist, is trained to fix some external problem. Art rarely succeeds when it sets out to fix anything beyond the artist’s own, subjective needs.

#3. Practice sanitizes a very messy process. It suggests that art making is a kind of white-collar activity whose practitioners don’t get their hands dirty, either physically or emotionally. It converts art into a hygienic desk job and signals a basic discomfort with the physical mess as well as the unknowable, irrational side of art making. It suggests that materials are not the point of art at all — when they are, on some level, the only point.

While I completely agree with #1 (that a formal degree while definitely useful is not essential to the development of an art mindset in an individual) and #3 (the subversion of materials around an artist constitutes an important part of artistic expression), I do have questions about #2 (the assertion that artists have a self-help, therapy based relationship with their art and it serves to solve personal, subjective problems rather than focus on larger global issues)…

I would say that in a large number of cases, the output produced by an artist may be directed to induce the viewer to think about (and in the ideal case, acting to alleviate) a problem hitherto unknown or underrepresented (sewer cleaners in India or a film about plantation workers in Dominica are two cases that come to mind). I might also add that artistic expressions such as the above stems from strong sincerity that the artist must have for the problem rather than being an accidental by-product while the artist indulged in self therapy…

Feedback appreciated.

Posted by Sunil Gangadharan on December 19th, 2007

True to the age of ‘my results NOW!’, the current trend towards digital manipulations of photos is a good case in point. Free image manipulation software now seem to bring out results that sometimes rival established image manipulation software like Photoshop in the aspects of touching up and sharpening digital photographs. Photographs of bananas on our kitchen counter top and a solitary ship in the New York harbor (that were then digitally manipulated using something as low tech as PAINT.NET) are shown below as an example…

Of course, there is a certain school which believes that the instant you alter your photographic images with software tools, you pollute the concept and the resulting image is not worth its salt. This may be true for images produced in scientific journals, but does not seem to hold true for a lot of amateur photographers (and some professional – especially folks who cover the news) who have clearly started to use these tools. Tell-tale signs are visible to a practiced eye and even if I do not claim too much practice myself, I did notice a couple of photography shows down in Chelsea where the images were clearly manipulated to suit the subject or the theme. Personally, I do not think there is anything sinful about manipulating an image. It is just that the chemical laced manipulations laboriously done inside that makeshift and cramped darkroom can now be done fairly easily in front of a computer. Of course, historically, ‘more effort’ is sometimes perceived as being ‘more original’ and the darkroom based morphs of yore were definitely heavy lifting.

What are your views as regards digital manipulation – especially considering that there are some very good photographers here on this forum…?

‘Cold ship’, Altered digital photograph

‘Bananas’, Altered digital photograph

Posted by Sunil Gangadharan on December 6th, 2007

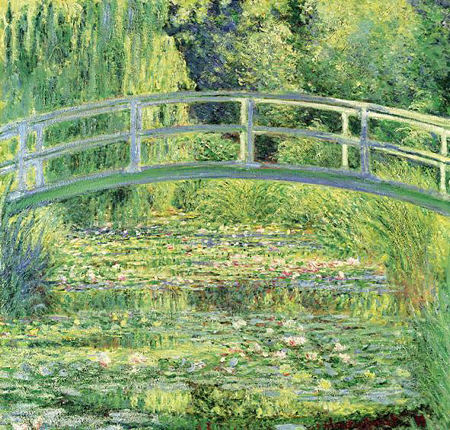

I was fascinated by the research of an ophthalmologist that focused on visual infirmities plaguing artists in their later years and the effects of the infirmity on their art in Tuesday’s New York Times science section.

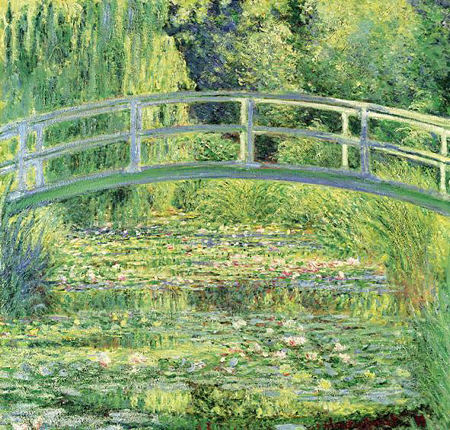

“On the fifth floor of the Museum of Modern Art, a three-canvas set of Monet’s water lilies spreads across a gallery wall in dazzling homage to the artist at the height of his brilliance. Off to one side is a painting of the Japanese bridge at Giverny from the early ’20s, when Monet’s cataracts were at their worst. It is a disturbing mix of dark reds and browns, much darker than the water lilies, yet just as compelling, perhaps, in its brooding intensity.”

“What has long been known about Monet’s later years is that he suffered from cataracts and that his eyesight worsened so much that he painted from memory. He acknowledged to an interviewer that he was “trusting solely to the labels on the tubes of paint and to the force of habit.”

Degas suffered macular degeneration, Renoir had rheumatoid arthritis, Mary Cassatt had cataracts and seizures attended to van Gogh. In almost all of these cases, the infirmities that attacked these famous artists happened after their places were assured in history as great artists.

This has led me to speculate that once an artist gains recognition, it does not really matter what that artist develops, we just look for and want confirmation of the fact that it was indeed painted by the person – be it illegible scrawls, colors incoherently massing into one other to form a dirty mess or just plain lack of attention to details (details that were earlier captured to meticulous effect) – it does not matter. We overlook incompetence (brought on by the onset of disease, drug overdose or otherwise) and reward the artist for what s(he) were once famous for…

Claude Monet, ‘Waterlily Pond’, 1899; Oil on canvas

Note: His vision problems did not start until 1912

Claude Monet, ‘The Japanese Bridge’, 1918; Oil on canvas