A while back, Birgit and I had a short discussion in the comment section about “Transcendental Art” but neither one of us were unable to expand upon the subject in a satisfactory way at the time.

I checked out the clippings from that long ago art magazine article and found, happily, that there is in fact an artist’s name listed with the art work. And I’m also happy to report that my Art History degree has paid off because after all these years I recognized the name of the artist.

So without further ado, the artist is…Richard Pousette-Dart (1916-1992).

Richard Pousette-Dart was an early member of the Abstract Expressionist movement that reached its apex in 1950s New York, and was not a stranger to Peggy Guggenheim’s This Century art gallery. He is one of the figures in the famous, and preciously titled, Life photograph The Irascibles, standing alongside de Kooning and Pollack.

Pousett-Dart on far left, second row

Despite his early association with this group, claiming Pousette-Dart is an Abstract Expressionist is putting a round hole in a square peg. However, his influence on artists such as de Kooning and Pollack is unmistakable. Pousette-Dart was also the first of these artists to create art on a large scale, something Pollack would do later to great effect.

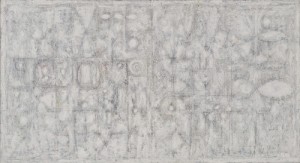

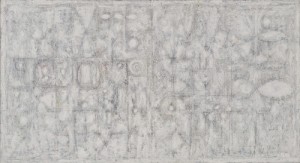

One of de Kooning’s greatest works is Excavation. And while it may seem tenuous at first, I believe Pousette-Dart’s influence is evident, as one can see here in the early Pousette-Dart piece Desert from 1940 which was made ten years before de Kooning’s Excavation.

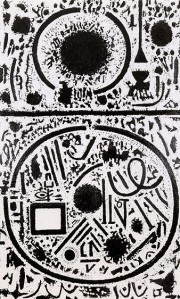

Desert 1940

Excavation 1950

Pousette-Dart was influenced at a fairly young age by the works of Jung and Freud, Northwest Indian culture and European Modernism. His body of work is an amalgam of these and more. Today one could be tempted to call it New Age but I feel that would weaken its meaning, given the heavy baggage the term New Age carries.

On his artistic journey he traveled through, in no particular order, the Modern art movements of Abstract Expressionism, Symbolism, Surrealism, Color Field painting and neo-Pointillism.

Pousette-Dart’s primary goal was to experience spiritual transcendence and expanded consciousness through the creation of his art, as well as the viewing of it. He believed that the spiritual was ever present.

Spirituality has many outlets, one of them being esotericism. Esoteric beliefs rely on symbols as teaching methods, the idea being that these symbols are ancient forms of communication which unveil profound truths to those that unlock their meanings.

Pousette-Dart’s work often uses symbols to describe the spiritual. In Desert one sees, although maybe not immediately, the eye at the center of the painting. There are also other, stylized eyes seen in the painting. More than likely in this case the large central eye is the Eye of Providence, also known as the all seeing eye of God, which is often surrounded by rays of light. This image can be found as far back as ancient Egyptian times, with the eye of Horus, and has been used in many cultures over many different periods, all with the overarching idea of a higher power.

In the esoteric the most basic of shapes can carry multiple meanings so that an eye, a triangle or a square may represent divinity, mathematics, physics and by extension, alchemy. And while Pousette-Dart was not overtly depicting esoteric beliefs, one can never assume a square is just a square in his works.

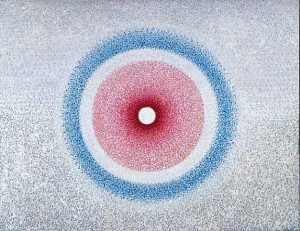

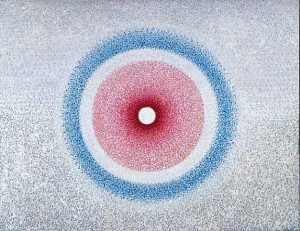

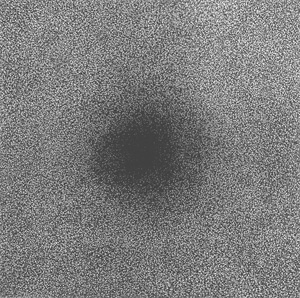

Light plays an important role in Pousette-Dart’s work, and appropriately so as light is an integral part of any transcendent experience. In the early work Desert, light is depicted primarily through the use of white, but through the years, Pousette-Dart’s imagery becomes overwhelmed by the light, fading into the background then returning in different forms so that the symbol itself is the focal point, often created in a neo-pointillism style as in Eye of Light from 1969.

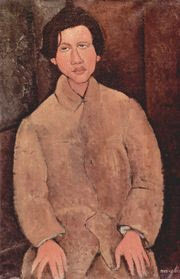

Chavade, 1951

Eye of Light

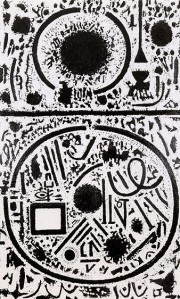

But where there is light there is darkness, and Pousette-Dart did not shy away from depicting the darkness, in fact he seemed to engage in a rather Manichean depiction of the two such as in his work Wall of Signs.

Wall of Signs

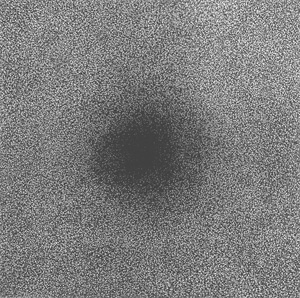

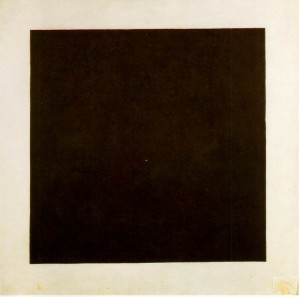

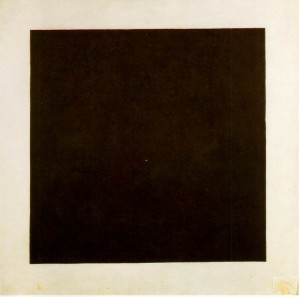

Black is used to great effect in his work Presence Number 3, Black from 1969. While the use of black and the word Presence can conjure a feeling of dark foreboding, I am reminded of Malevich’s Black Square. If the square is God, neatly self contained, if at the same time endless, then this is God exploded out into tiny specks, i.e. “us.” Given the large size of the work, I’m sure a physical viewing would also make for an intense experience.

Presence Number 3, Black, detail

Black Square

I believe there are relatively few who speak the true language of spiritual transcendence and expanded consciousness. Often these experiences are cheapened by religion, fake gurus and televangelists. The real experiences are more often than not solitary and inexpressible; as the experiences are so profound there simply are no words to explain them. For those who have had these experiences, viewing much of Pousette-Dart’s work is a silent communion. For those who may not understand that, there is still much to absorb in the way of cultural imagery and symbols as well as a tour through a variety of Modern art styles.