As an oil painter who tends toward “moosh” rather than clean graphic edges, I have found myself pondering the stitched line intrinsic to my quilted paintings. They change the moosh that I so often fall into, adding a different set of visual ideas.

So, if you’ll forgive me, I want to explore notions of line — line mostly as it is generally described and discussed in design classes, but more particularly as it works in quilted art. [ed. note: This turned out to be more of an essay than I had intended. If you wish, you can just look at the pretty pictures.]

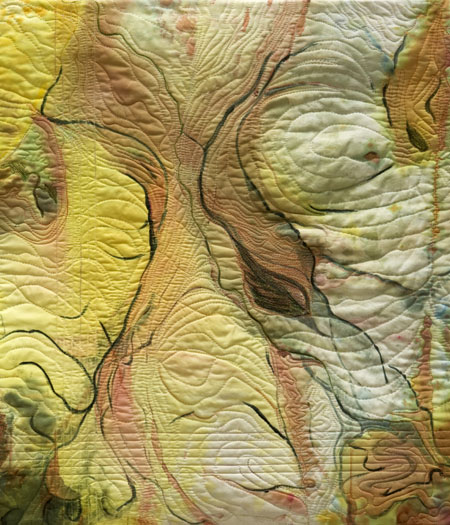

Painted Hills Bluff, detail (Work in Progress)

Line is important in design, particularly, of course, in drawing. It moves the eye, evokes feelings, defines or suggests shape, can make value and depth, and can be varied to vary its expressive quality. In quilted art, line functions in all these ways, but can have a weight and value different from that found in drawing and is far more inportant than line is in painting. In conventional photography, line seems to have minor function, but art photography often makes extensive use of line.

Originally the quilting line was structural and functional. Over time, its usage in the US acquired certain conventions and standards (probably because of dressmaking conventions and county extension agents). The convention was that quilting stitches should be small and even, that the back thread should be hidden by burying it in the middle layer of batting, that regular patterns of grids, feathers, florals, stitch-in-the-ditch, and echo quilting were sufficient designs for the quilted stitch.

However, as artists took up stitching fabric and making quilted art, the conventions quickly gave way to attention to design elements, and the quilted line began to evolve. It became as important to the visual effect as the more obvious surface design.

The quilting line can be of many colors and weights, and decisions about whether to choose a hue similar to the background or to pick a complementary hue, whether to use a thin embroidery weight thread or a thick yarn sewn from the back, all became tools with which the artist could work.

Shore Pine. detail

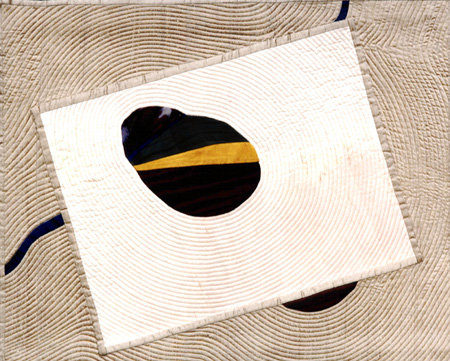

Some stitching is meant to be unobtrusive, to push the background back. The basic stitch that serves this purpose is called a stipple stitch, which varies in its character and shape but has as its purpose flattening and giving an all-over appearance to the stitched area.

Arabesque, detail

Line, as we know, describes shape, and the quilting line can also serve this purpose. It can describe a contour or outline a shape. A shape echoed by a quilting line has a clarity about it that is pleasing. It can be a kind of shorthand for a more thoroughly painted out form.

Above Cant Ranch

However, the stitched line can also serve to contradict the shape, to pull and distort it, and in this, it serves the purpose that only an impasto line of paint can serve.

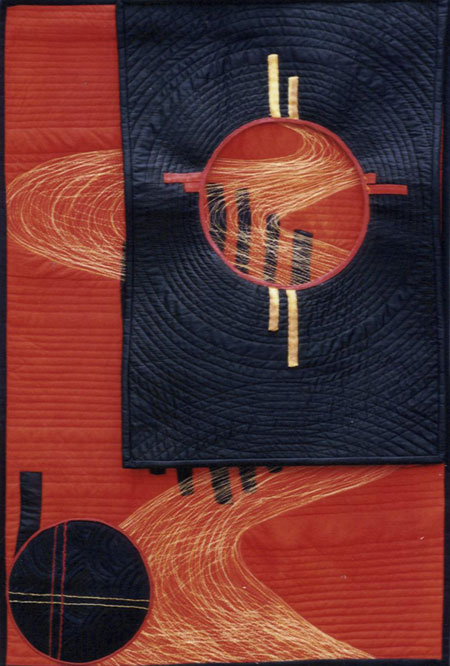

Updraft

And the extended use of the echo stitch, a continuing of the contour, enlarges and makes fir outward movement. In the example below, the image is relatively static, but given movement by the stitching. The regular spacing of the stitched lines reminds me of etchings, but the shadowing and puffing of the fabric can only be done in textiles.

The Dream

And a quilted grid or regular figure behind a painted surface can help control or change the emotional weight of the surface figuration:

Ms Patsy

The quilting line, like the lines found in drawings and paintings, can be implied as well as obvious. They can provide movement around the canvas, following the implied lines.

Zen View Red

The direction of the line, as design instructors have told us since time immemorial, can indicate peace (centered/horizontal), calm vitality (vertical), or movement (diagonals).

The Mother of Us All, Detail

The quilting line, in short, is extremely expressive — as it varies in its tight or looseness, the weight of the thread and the density of the application, the curve or flow or jaggedness or griddedness or angularity — it can enclose or jolt, dance or confuse.

Interior: all Silk

Line can even be overlapped until it becomes shape — traditional etchers were masters at this, and the use of embroidery in quilt art can likewise make its own forms.

Pussy Willow

A few other ways line is used — for perspective:

Montana Garden

And for suggestions of ideas or emotions, not quite clear but highly evocative:

Mrs. Willard Waits, detail

Finally, part of the difference between the line on the canvas or paper and the line in a quilted surface resides in the textured quality that only quilting can give. A quilting line makes a shadow because it pushes the quilt sandwich into itself and puffs the non-quilted space outward, shading the edges. A quilted line engaging the abutting cloth makes shading and modeling of its own accord. It isn’t merely a moving dot, it becomes a swath across the surface of the cloth. It make air palpable; it creates folds of meaning and desire where only color existed before.

Clothesline, Detail

Miocene, detail

What part does line have in your work? Hanneke used an exquisite line around the edge of the open peach, a line that feels precisely right. Sunil is moving away from line into more painterly work. Steve is abstracting his photographs until line and shape become predominate.

For me, as enamored of stretched canvas and oil paints as I am, I still find enormous power in the stitched quilting line. .

Painted Hills Bluff, work in progress (see the pins?)

This is so well thought out, June! I had a lightbulb moment while reading it. Those qualities of relief and line, complimentary or contradictory, the play of light and shadow, is what drew me to my first medium, etching and intaglio printmaking, and is what draws me to my current medium of art quilting. In my head they’re the same, (even though they’re really not), although I’ve never given conscious thought to it before. And now I see why I’ve been compelled lately to try to combine the two, because of all of the qualities they share.

Thank you for the opporunity to stop and think. If more artists realized how very much we quilt artists can do with line, there might be more artists exploring quilt as medium.

June,

I’m flabbergasted (and I never use that word) with what you are doing here. Amazing. I have to confess that the line/non-line issue is not so important to me in this initial intake of all of this lovely work. I’ll need to ponder the topic more carefully.

(P.S. loved you recent landscapes, if you didn’t see the comment).

June,

This is an amazing compendium! What is especially interesting to me is the quilter’s ability to use line independently of form and color. In photography, line generally arises at the boundary of significant forms. My last image two posts back, of the crack lines within the roof planks, attracted my attention partly because it was unusual in this regard.

Is every line you sew a commitment? Is it feasible to sew a trial stitch and then remove it easily if you don’t like the effect?

Jane, Karl, and Steve,

Thanks for the comments.

Jane, I have a friend who is a classic printmaker and I am always astonished at his work. I find that he and I have a lot of artistic concerns in common and we form a mutual admiration society. Of course, there are differences as well — quilting makes such a yummy texture.

Karl, thank you for the lovely words. I did see your comment on the landscapes and I was deeply flattered, since I know you do pleine aire work. Please do think on the issue of “line” and let me know if you have further thoughts. I’m trying to suss it out as deeply as possible.

Steve, I was definitely seeing your work when I realized that, generally speaking, photograpy is not about line, but sometimes it is.

I can rip out a quilted line that I’ve misplaced (and believe me, I’ve done lots of such work — the quilter’s joke is the frogs and quilters have something in common — rib-bit, rib-bit, rib-bit.) With some textiles, the results of taking out a line are virtually unnoticeable — the fabric heals itself. In others, particularly if the fabric is heavily sized or has been painted with acrylic paint, the holes which the stitching leaves have to be incorporated somehow in the design — they are very visible.

But on the other hand, because I quilt densely and on imagery that has a lot of flex, I almost always can make do with a line that is slightly off by balancing it with another line or some such.

As for trials, people can use plastic overlays to draw tentative lines for quilting. You can also put a crease in the fabric with your thumbnail and get an idea of what would work. But after 15 years or so of using the quilting stitch intensely, I almost always work intuitively and with only the sparest of pre-viewed lines to get me started. Then I am off and running, improvising as I go.

June,

I can appreciate much more what you are doing by seeing these blow-ups. Amazing.

More later,I am totally preoccupied with my ‘day job’ in a good way.

You have done a wonderful job of explaining why I work with fabrics instead of just painting canvas–the texture of the quilted line adds so much to a piece. Lately I’ve been including both organic shapes and geometric closely spaced lines just to further exploit this added benefit of using textiles.

This essay of yours belongs in print–maybe the SAQA or SDA journal?

June,

“Painted Hills Bluff” is stunning, absolutely gorgeous. Not simply the lines, but the light and texture. Superb! The quilted line adds a literal as well as figurative depth — visual and tactile texture. Perhaps the interplays of these add more than the sum of their parts.

Birgit,

Preoccupation in a good way is good — regardless of the context. Enjoy!

BJ — I would love to work this up for a printed source. But I lack the connections to get an editor’s attention. Thanks for the compliments, though. I think I’m also explaining things to myself….

Clairan, I’m happy with the way Painted Hills Bluff is coming out — it’s pretty heavy quilting duty on the framing tree.

We’ll see what happens when I get to the foreground — sometimes lines, like that of the fence railing, can go terribly awry (ribbet, ribbet, ribbet). When I was first learning to quilt I had 5 seam rippers. Now I’m down to 1.5 — the .5 is for when I can’t find the 1.

June,

I broke 2 rippers this week! Toadily true!

June,

After writing and backspacing here for many minutes, I realize I’m at a loss for words.

I cannot match the magnitude of these pieces. The first just sent me spinning, and it was overwhelm thereafter. I wish I could afford one of these. You are brilliant. Thank you.

Thank you, Rex, and welcome back. It’s good to hear your voice again. And particularly when you are saying such good things (now you have to insert that snort).

By the way, someone who saw this wrote me to say that I missed a whole set of elements of the quilted line, those in which the line makes shapes which form images. I don’t do that sort of thing (or at least not very often) but I have seen great and whimsical examples of it.

To make images of the quilted line is to assert the independence of that line even more strongly. Interestingly enough, the technique has a basis in traditional bed quilts, which often had floral patterns stitched across them while the top was, perhaps, pieced squares. But to integrate the subtlety of the line into an image which then is composed to work with the surface, more obvious images — hmmm, that’s an interesting problem.

What a well thought out exposition on the role of line in quilting. You force me to think about my own work with a fresh perspective; thanks for that!

For me, line defines shape; color is secondary. Because in my best efforts, my “Spirit Works,” I quilt first, then paint after, line is virtually EVERYTHING.

Without line, I would have no form. I simply would not know where to place which color! My work depends entirely on the sewn line. And it’s nice to know that even after the piece has been painted, I can always go back in and add some more lines if I want to.

I’m only terrifically envious of your sensitivity. Why didn’t I write this article first?!? ;-)

Dena in Kenya

Dear June,

You have done it again…sent my head spinning. Thanks so much for the wonderful explanation of why I love this fabric medium. For me line is the key.

Peg

June,

I now understand why you do not sew by hand. It would be totally ridiculous even to attempt it.

At school, I learned to do different kinds of stitches by hand. A few years ago, I bought a book on ethnic stitching. Some of those stitches are lovely.

But that is not what you do. Your stitching is etching using fabric. I assume that if you did not invent this genre, you advanced it a thousand fold.

I admire your breadth, playful to

awesome, somber to flashy.

Of the pieces that resonate most with me this morning are Updraft, Mother of Us All, Montana Garden, Miocene, and Painted Hills.

Line plays an important part in all my work, textile or otherwise. What I’m finding interesting at the moment is making a drawing on a piece of (say) handdyed, handpainted cloth, rather than using the shapes and tones of the handdye to suggest the drawings. I also like to vary the length of the machine stitch (anathema to purists!). I’m only at the beginning of this particular journey, and think I’ve got quite a way to go.

Interesting article, June, thanks.

June, a lovely essay. I hope you can get it in print. SAQA Journal? Would Quilt Art publish it (although they go in so heavily on embellishment, but shame on them if they ignore a query from you.) Surely there is some magazine I don’t know about that would snap it up.

I myself avoid handwork in my own art quilts, but admire the hand stitch in many quilts. It was a revelation to me that relatively large *uneven* stitches were much more interesting than even small ones, especially when used over an area instead of along a single line.

Comparing our stitched line to a painter (mainly from a ‘mechanical’ viewpoint) – with a brush you can make a line of various widths in a single stroke. Our thread is always thin in comparison. If we build up the thichness with repeated stitching, is it still a line, or has it become a shape (with area)?

Your landscapes are awesome, June. You seem to have really found something of such meaning to you. I was at the Georgia O’Keefe museum last month, and was surprised to see she painted pure landscapes (I had seen only her flowers and skulls and cities before). The first thing that popped in my head when I saw her landscape of a river valley was “June Underwood!”

… and one more comment on the stitched line in making a quilted landscape – one difficulty with such a line is that it doesn’t convey perspective well. In a piece like Above Cant Ranch, you get the same ‘hard’ line if it is 10 feet from you or on a distant mountain, which makes the landscape appear to be all in the same plane. A painter could blur or soften that line so it was less apparent on distant landscape features.

Perhaps if the distant lines were sewn on the quilt top only, and not during the quilting, it would not get the shadowing affect from the dimensionality of quilting and that would give it the ‘blur’.

Clear as mud, I’m afraid…

Thanks, all, for the comments. I’m afraid the non- quilting artists on this list will realize now that I’m not the sui generis that they may have assumed — that there are lots of us out there playing with the stitch. Sigh — I have to admit to being just one of many.

Dena, I’m going to have to go back and look again at your work. Painting after the stitching is something I’ve tried, but without much success. Perhaps I quit too soon.

Peg, good to hear from you.

Birgit, I love “etching using fiber.” That really works for me. Hand stitching is related but very different in effect and flexibility. Dorothy Caldwell does amazingly beautiful huge pieces with hand stitching, eccentric and moving. But I love working with the machine — it really does feel like a collaborative effort to me. I talk to it, it talks to me, we rush or rumble or jive around the fabric. It even bulks and complains when I’ve neglected it for the oil painting.

And Birgit, your list of favorites is a delight, in part because they feel so unlike one another in my brain. But then when I think about it, they are all products of the last two years, whereas many of the other works come from as far back as 12–14 years ago.

Marion, you and I have been playing with the stitch (sometimes together) for years. Marion is from the UK and I’ve never seen her in person, but I’ve admired her work and processes and she has set something of an example for me in her on-going explorations.

Varying the stitch length is a no-brainer for me. More about that when I answer Eileen’s notes.

Eileen,

I’ll pick your brains privately about publishing — thank you for mentioning it.

Varying stitch lengths as well as the weight of the thread is relatively easy to do with machine stitching, Particularly the stitch length in free motion work depends on the speed of the needle as it punctures the fibers vis-a-vis the speed that you move the quilt under the needle. So that’s under the artist’s control.

More difficult is varying — and controlling the variation — of the stitch width. I have couched yarns that provide varying throughout the skein, but the width of the line of yarn is fixed by the yarn itself — it’s more difficult to decide to make a wider line when the yarn has thinned out. It’s possible but maddening to work with with any intentionality.

And the conundrum of shape/line is of course eternal and what gives art teachers so much to talk about — positive and negative shapes indeed.

And finally Eileen, it’s interesting that you are thinking about distance and the quilting line, as I was just playing (unsuccessfully, I’ll admit) with that concept. (An aside: Cant Ranch is meant to be flat — I was in my “flat” mode, playing with shape as shape, with representation a secondary or tertiary consideration).

My (current) solution to the distance-using-line challenge is to decrease the distance between the lines — making the close-in ones wide apart and the more distant one closer together — just as you would see in fence posts as they travel away from you. Your idea is an interesting one — to remove the shadowing effect by stitching without the batting. I shall have to ponder that and maybe even try it — thin thread, I think. And of course, the toning of the thread into grays and blues to give a sense of distance is a natural — the paint begins the process and the thread can continue it.

Many thanks for the comments — they are valuable and have gotten me thinking through the process again — and again –and again.

Hi June,

Wonderful essay! I want to question the response made to Eileen in the latest response, regarding the use of quilted lines in perspective: is that line still considered ‘quilted’ if the thickness is removed to avoid the shadows produced? Does the quilted line imply a certain amount of shadowing simply as a result of the nature of the construction and process of quiltmaking? I understand that quilting need consist only of 2 layers; does it hold than that the 2 layers can be cotton each, or some other thin fabrics that don’t promote the shadowy effects of quilted lines sewn through more dense layers? Are the shadowy effects of the quilting line an identifier, something that helps shape the definition of ‘quilting’?.

Is this another rule that can be broken in the name of informed art?

Well done June. I am also struck by the range of your art work, both by idea and by execution.

Sue

Sue,

At the risk of sounding snarky, I have to ask — why is the question important? Why ask it?

Well, part of the answer, I’m sure, is that some artists who use quilting techniques exhibit in “quilt” shows, where “quilting” is expected. In that case, the show organizers probably have an answer for you.

As for myself, I use quilting techniques and embroidery techniques and watercolor techniques and acylic painting techniques and old-fashioned sewing techniques (both hand and machine) as well as the computer and digitized imagery management. When I figure out how to include oil painting techniques and material, I’ll be in heaven.

I think a definition of “quilting” is irrelevant when the goal is to make art. When to goal is to make quilts, then it’s a different story.

A far more important question for me is what happens to the image when you use a single fabric layer; what happens when you double the fabric layer; what happens when you use fusible batting (some very interesting things, as it happens).

I hope I’m making clear what I’m trying to do and why I think the definition of “quilting” is irrelevant. The operative phrase is “conventional quilting techniques” which allows me a lot of latitude.

You’ve made your thoughts clear June. I am surprised by the statement ‘the definition of quilting is irrelevant when the goal is to make art’. There are lines of sewing, lines of couching, lines of embroidery,lines of quilting… I suppose there must be a definition of each if they are to be considered as separate and useful tools in the execution of a design. In this essay you are speaking of quilted lines. Does the phrase ‘conventional quilting techniques’ encompass some, or all, or more than, the above?

Just hoping for clarity here. I think my original question was valid, and was not intended as a judgment statement about what is or is not an art piece that includes quilted lines.

Sue

Hi Sue,

I can see that precision in understanding the making of the lines is important. And so it might be useful to have a shorthand method of talking about them — quilting line with batting; quilting line without batting; stitching line on single piece of fabric. But as for a “definition of quilting” which deals with the shadow or lack thereof doesn’t seem very useful.

Your question, to repeat it, was: “is that line still considered ‘quilted’ if the thickness is removed to avoid the shadows produced? Does the quilted line imply a certain amount of shadowing simply as a result of the nature of the construction and process of quiltmaking? … Are the shadowy effects of the quilting line an identifier, something that helps shape the definition of ‘quilting’?.

As I reread this, it seems to me you are asking about the “shadowy effects” created by the stitched line as the “identifier” of the term, and that effect is dependent upon the amount of material on or through which it is stitched. But the effect — the “shadow” of which you speak — also differs if you are stitching through linen or silk or cottons of various sorts or wools or canvas for that matter. Wouldn’t we have to address the question of whether it can be called quilting if it’s stitched on canvas, even through three layers, because there you would lose the shadow given the stiffness of the fabric. Likewise with wool quilts which are often tied because the stitching line gets very lost but are still seen as “quilts” in the traditional use of the term. In other words, your question gets converted quickly into a quagmire that might not be of any use.

I think I was also startled by your question: “Is this another rule that can be broken in the name of informed art?” In my eyes, about art there are no rules, only useful effects.

I can see that breaking down the “lines” into sewing, couching, embroidery, quilting would be useful for discussions of each, and I definitely glommed them together as “quilted” line. But I do think that “conventional quilting techniques” encompasses all of them — they are sub-categories of the more generalized phrase.

I knew you weren’t intending a judgment statement (and your initial judgment of the work itself was in fact very kind) but as you may have guessed, I think the tendency toward making a description into a definition which then becomes a rule and then applying it to art can be seriously detrimental to our art making.

But then, I concede, yes, the effect of the shadow, dim or clear or middlin’ that the stitcher achieves in making a quilted line (however that line is made) is an important element that distinguishes quilt lines from painted or drawn ones. Does that help?

I’ve fallen, hook, LINE, and sinker for your extraordinarily well-illustrated essay, June. No need to fish for compliments; you are awesome. As I’m in publishing, I’m angling to see this as a little book. However, we often speak about photographs of our fiberart an unfit reflection of the play on light, the tactile, soft fabric, the threads that most often provide the design line, texture, and mood. So, I’ll just have to look forward to seeing your work in the cloth in future exhibitions…a one-woman show, perhaps?–Eleanor Levie

I am finding I cannot get the first piece, Painted Hills Bluff, out of my mind. I don’t want to either.

June, would you consider making a print available? It would take some masterful photography to reveal the texture, and much would be lost, surely, but there is SO MUCH there.

Hi Eleanor,

Thank you. Thank you.

I would love to publish some version of this post (and have a solo show, too). If you know any editors who might be interested, send them my way.

I have had solo shows, but only in the Portland region. One reason why I’m not leaping at publishing is that I can only stand to beg so much before I lose heart. So I save my begging (“please, m’am, would you consider a bit of etched fabric for your gallery”) for exhibits. I do have a list of group shows I’ll be participating in on my website.

You have beautiful work, June. One thing I’ve always liked about quilts is that they tell (at least) two stories; one in the design and another with the stitching.

Hi tree/Kimberly

The quilting line is a tremendous tool — it can be used to expand a single story or to tell a different one that tugs at the original or tell a story parallel to the surface design. I have found nothing that works in the same way in painting, except perhaps impasto.

On the other hand, the images one can achieve on textiles, unstretched and ungessoed, sometimes require the quilted line to fill them out, make them worth contemplating. What was it Birgit quoted from Van Gogh “making a painting that is worth teaching”?? Something like that. The quilted line can make a vision worth teaching out of something that is lesser without it.

Dear heavens, it was Cezanne that Birgit was quoting and the quote is far better than my paraphrase:

Birgit wrote: “just read a Cezanne quote

‘The painter ought to consecrate himself entirely to the study of nature and try to produce pictures which will be a teaching.'”

I think I had one glass of wine too many.

“produce pictures that will be a teaching.” What a fine phrase.

Updraft and Painted Hills Bluff are my favorites. I never knew such emotions are possible to put down with quilting. Your work and the complexities inherent in this form gave me renewed interest to read the obituary of Lenore Tawney this morning.

Great topic and discussion June! I have been occupied with the possiblities of the stitched line since I first started making art quilts. It’s often a communication device, especially last week when I thought of making my own hieroglyphs to cover an Egyptian-themed quilt.

http://pamdora.com/blog/2007/09/28/576/

For me it’s also a delicate balance between how much of the stitched line to show in contrast to the prints on the fabric and the graphic symbols that the fabric is cut into.

Other times I view the stitched line as a record of my meditative thought as I quilt.

Sunil,

Interesting that you should mention Leonore Tawney. In part, my essay was prompted by a review I read of her 1990 retrospective. The reviewer, Roberta Smith of the NY Times, is one I like a lot, but she fell short, it seemed to me, in looking at Tawney’s work. It was as if she couldn’t get beyond the idea of weaving and thread to see the art. That led me to thinking about how much education is needed to get people to see what it is that we who use the quilted line are doing — how what we do informs the fullness of the art and is as essential to it as the surface imagery — sometimes more so.

On another blog in which I participate, the Ragged Cloth Cafe, Clairan has a nice post on Lenore Tawney. Clairan comments on this blog from time to time.

PaMdora,

Your “hieroglyphs” in your latest work are a form of what I call, for lack of a better general term, a stipple stitch. That is, it’s an overall stitching, which can take many shapes, but whose purpose is primarily to flatten and secure some part of the materials. It’s fun to use that general quality to achieve a quiet secondary effect — in your case, heiroglyphics. I have a piece called Mrs. Willard Waltzes with the Wisteria, in which I made background stipple stitching into the foot patterns of the waltz. It was great fun.

While I have sometimes thought that the quilted line works to enhance the surface image, I have come around to thinking sometimes just the opposite — the surface images is there to enhance the stitched line.

June:

Wonderful. Love the railings in your last piece and would ask that they remain unstitched.

Dreamed last night that you and Jer had gone out and bought a big shiny sports car.

I posted my copious city and guilds notes on Line on my blog…planned to do a book someday. Have notes like this one all the elements of design. Exercises included

http://www.kimritter.com/weblog/

You have written about exactly what I am struggling and experimenting with right now. The quality and value of line from charcoal and conte drawing is something I’m trying to bring into my quilting.

Jay,

leave those railings, eh? Might do that — haven’t gotten to them yet. I always have to worry about the silk sagging where it’s not stitched, so I’ll ponder on it.

A shiny sports car is precisely what we are all about, right????

Kim, I looked at your blog. How do you intend to go beyond the text-book, class note approach? You have done a lot of ground work but text-wise, the notes are pretty much what has already been done by Ann Johnston and David Lauer. I’d venture to guess that your instructor was working directly from Lauer.

Thanks, Connie, — if you have any insights into charcoal and conte and how they inform the quilted line (and vice-versa), I’d love to hear it.

I will be beyond internet access for a week, so don’t despair if you write and I don’t comment. I’ll be back with you soon.

June:

And please do write a book. I would think that you could do it in a few days.

It was one of those long low things put out by Chrysler and Jer wore those English-style motorist’s goggles and gripped the wheel with an evil grin.

June – all the best with publishing this post and the answers that it has drawn – pun intended. I hope eventually all quilt makers will think more deeply about how we use the stitched line.

The stitched line either outlines shapes or may be manipulated into a texture. As artists, quilters use a wide array of surface design techniques on the primary surface – dyes, paints, collage, piecing and their multitude of specialised forms. plus stitched lines without batting, or ’embroidery’. This can then be enhanced with additional layers and further hand or machine stitching to producing the low relief quilted surface. The choice of an appropriate quilting design is one of my things – even people who spend a lot of time and effort on the surface design can reduce the overall impact with thoughless quilting treatment. Finding nspiration for appropriate quilting design is one of my concerns – I blogged about it oct 7th, http://www.alisonschwabe.blogspot.com