In a recent critique session of quilted art, conducted by two “fine” artists, I found myself having a “eureka” moment. Then, a few days ago, Jay and Melanie’s discussion of Jay’s intaglio technique on board and foamcore (published prior to this post) pushed some of my insights a bit further. All this was added into a melange of thinking I’ve been doing about where I am in relation to quilted art and painted art.

The eureka moment came through the phrase used by one of the fine art critics: the phrase was “working the surface.” “Working the surface” in the traditional fine arts means adding, deleting, scraping, underpainting and overpainting, sanding, gouging — all the kinds of things one can do that either uncover and/or add to a planar surface. It seems clear to me that Jay’s process of working his boards and foamcore are fine examples of “working the surface.”

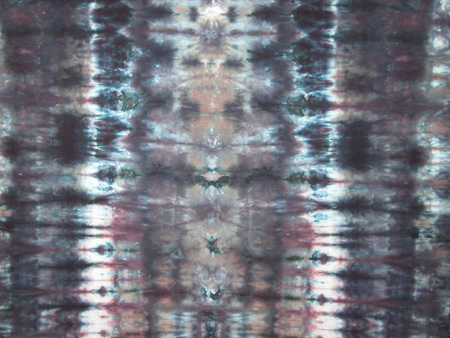

With quilted art, “working the surface” seems to show up in two ways. One is what is called “surface design,” which basically alters the flat plane, by dyeing it, laying rust on it, discharging (bleaching) it, monoprinting on it, and even digging into it, tearing and unraveling the threadwork. This work sometimes adds texture (especially with elements applied to the surface (applique) or taken away from it (“cutwork” or just plain gouging holes). These kinds of working of the plane are singular, patterned for the effect in a particular work, not meant to be turned into a commercial design for fabric (the original use of “surface design” had a strong commercial element.) The other part of working the surface with textiles is the work of embroidery and quilted lines that make for a frieze effect; when stitches are pushed through the two layers of fabric and the in-between batting or wadding, the stitched line makes an indentation, beside which the surface becomes raised by the pushed-aside materials.

I have never heard the phrase, “working the surface” applied to quilted art before, but when I heard that and then saw the intricacies of Jay’s working of his surfaces, I realized that the language may give me new insights into what can be done with quilted art.

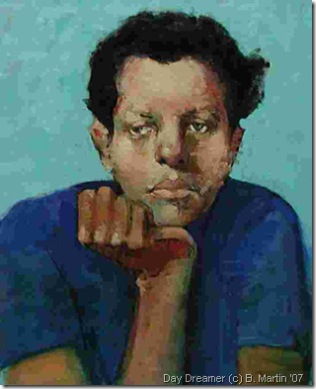

At the critique, the guest “critics” (very kind observant folks) looked at two pieces I had brought, comparing them.

The first was one you’ve seen before: Mrs. Willard Waltzes with the Wisteria, 76 x 61″, 2003, hand dyed and painted cotton, embroiderie perse with computer-generated prints, and dyed overlays.

detail

detail

more… »

detail

detail