Here at the Montana Artists Refuge, I find myself limited to the materials and ideas at hand. In Portland, I have access to two physical locations of Powell’s books as well as various used book stores and the big national chains. I also am within easy travel distance of four large art supply stores. Delivery of online orders is fast and easy. In Basin Montana, none of the above are present. So I have to make do with what I have available to me. And what I have available is sometimes just eccentric enough to be more than merely useful.

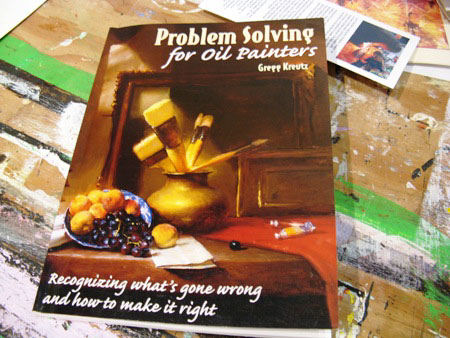

Along with my Phaidon biography of Cezanne (by Mary Tompkins Lewis) and a Dover book of Durer’s Drawings, I brought a copy of Gregg Kreutz‘s Problem Solving for Oil Painters. The book resides in my studio where I thumb through it when I need to rest my fingers and arm and eye from the physical act of painting.

I’m not recommending (and yet not not recommending) the book exactly; Kreutz is a bit too dogmatic for my tastes. Yet he does give me some things to push off from.

Sometimes he says the obvious, but when it’s placed with other ideas, it feeds my own delight in structuring thoughts. For example, he says “turning reality into painterly effects requires not only creativity but insight and empathy…. Insight and perception — each element must create an idea in the painter’s mind.”

And a bit later, “Every painting must have …two subjects — the person or still life or view that you are looking at and the painterly concept that you will have decided will best express your reaction to that [motif].

Not bad, says I, but I would add a couple more elements to the requirement for making a good painting: first there’s the subject itself that must be depicted, explored, played with, and, duh, painted; then there’s the empathy and insight that the painter brings to the subject; third there are the painterly constructs, the actual materials and handling and delivery, that go into making a physical object to look at — these differ widely but must be thought about and made to work with the object and the empathy; Finally, the controlling idea of the painting has to be there when it’s finished.

The High Note Cafe, 12 x 16, oil on board.

So I find myself pleased — Kreutz has started me thinking and I’ve completed some thoughts beyond what he says. Of course, this might well be what he had in mind, since problem solving is his subject.

However, while much of what he says is ho-hum or immediately useful in solving a problem, some of what he says makes me argufy.

For example, he says, “For the painting to give satisfaction to you while you’re painting, and to the viewer afterward, there must be a sense of problems being solved.”

Huh?, I say, “is this true?” Sometimes it’s the absolute lack of of a sense of problem that leads me to love work. I think of Hanneke’s still lifes and it’s the effortlessness that they give the appearance of that thrills me.

Of course, Kreutz’s further observations on any given dogma often are useful, which is why I brought the book with me. For example, in discussing shadows on faces, he says, “remember, the shadow doesn’t get lighter as it nears the light, the light gets darker.” That seems quite close to a philosophical position, found in the center of a “how-to” paragraph. i’m still pondering the implications for aging and tired concepts that “the light gets darker” can have.

Kreutz’s position on organizing the palette tends to send me into snits: “Is your palette efficiently organized? he asks, and then recommends a rigid structuring of color and layout, with a palette that’s bigger than many of my paintings. While his basic concept, that “making pictures is hard enough without the material and craft side of it holding you back” is a good one, he talks of spending forty-five minutes in the morning, setting up his palette, cleaning off the dried skin, adding paint, cleaning the mixing area, and so forth.

If it took me forty-five minutes to start my day’s work, I’d be frustrated and bored ( a terrible combination of feelings) before I began. For my palette processes, I use a wax paper layer over an ordinary sized plastic palette, throw it out when it gets messy, have a general notion of where the three primary colors go with white in the middle and blacks around the edges. It takes me three minutes to set up in the morning. But at night, I generally get ready for the next day, not just cleaning brushes and tidying messes, but also refilling medium containers, saving or tossing the paint, and studying what I have done during the day so my brain can be thinking about the next steps while I sleep. It’s almost exactly the opposite of the process that Kreutz uses.

Kreutz endears himself to me when he validates my own processes, of course. He says more than three colors in combination are redundant — and then admits he often violates this concept. Exactly.

He speaks of attacking a bad painting with his palette knife; in a “fit of pique” he scrapes off all the paint and finds good things in what remains. He also uses his palette knife to blob paint on a painting where it needs emphasis, a most satisfying combination of physical action and resulting vision corresponding. I use the palette knife in almost exactly these aggressive physical ways. And my textile training gives me the additional tool of scissors:

I would never be mulling much over Kreutz, except that, here in my Banker’s building studio in Basin Montana, my resources are limited. I find that the bits and pieces I read feed my thinking in a way that a larger set of resources and long pieces of dogma wouldn’t. It’s lovely that limitations can springboards for some thinking about my own ideas and processes.

What ideas or processes used by someone else have set you up for refining your own concepts and processes? Have you ever found that being forcibly limited in access to materials or ideas to be a broadening experience? Do you work better when you disagree with the “expert” opinion?

To that last question, I must admit that, yes, disagreement often fuels my creativity, even when I come around to agreeing in the end.

June,

I’m intrigued by the subtitle of the book: does Kreutz have anything interesting to say about recognizing what’s gone wrong? That seems the hardest part to me.

Perhaps it’s trivial, but the problem solved by Hanneke’s still lifes may be simply how to portray the subject so realistically. Some of the particular issues have been mentioned in her previous posts.

As for refining concepts and processes, that can happen as I’m thinking about something I’ve done. But you’re right, it happens at least as often when I’m trying to understand my negative reaction to something someone else has written or said or done. For example, I have an antipathy toward postcard-style scenic photographs, even though some are quite well done. I try to figure out what is lacking there (if it is), despite an initial “wow” reaction.

June,

I am impressed by your determination at painting. All I have done so far last November is to do two under paintings of dune scenes. Instead, I spent my free time enjoying photography with the wonderful camera that I bought last spring. I have also been reading photography news and lusting after one of the new full-sensor cameras.

As you know, I continued taking pictures in Germany over the holidays when suddenly my original dream to play with perspective resurfaced in my brain, making me laugh at my desire for a new camera. My ‘old’ camera will serve me well capturing textures and colors.

I am now ready to spend more time drawing. Oil painting probably will have to wait until I am further ahead wrapping up my day job.

In my case, I think, it was not a limitation of materials but rather the break in my routine that allowed my brain to remind me of my original interest – playing with perspectives.

June-

I feel like my work comes out of a deprivation of not only materials but any kind of artistic community/humanity around me! I live (for now–hopefully not forever!) in a very rural part of the world and my job involves working with practical & grounded country people.

The physical isolation and the contrast of my inner life to my outer cirumstance probably is why I find myself writing about art so often–I find that I don’t need the external validation I once needed because I have gotten so used to creating and thinking without it.

Hawthorne spend nearly a decade working on his craft in isolation (age 26-35 or something) and often referred to his work as “shadowy” and without substance since he had so little experience out in life…it was all out of his imagination. But this incubation period seemed to work for him. Perhaps, as you say, some deprivation of both materials and subjects is good.

Whatever the resource limitations, June’s production doesn’t seem to have been slowed much. Apparently it’s at 44 pieces and counting, according to a local newspaper article.

Steve:

Could you comment further about “picture postcard” photos? The reason I ask is that I fancy that I can recognize such a thing, but am not sure. Is it a matter of image size, choice of subject matter, response to a perceived preference in a target market? It might be profitable to compare scenery a la the postcard to that which graces a wall calendar. Calendar pictures can breath better and can carry a Monet picture, for example, much more successfully than can a 3×5 format. I agree with your comment about the relative merits of post cards, but I wonder if choices aren’t made for reasons particular to the format. It seems that anything committed to 3×5 will become a “postcard” view, be it something rote or one of your excellent images of the mountains.

Steve,

Kreutz begins each section of his book (“Idea, Shapes, Value, Light, Shadows, Depth, Solidity, Color, Paint”) with a statement of what is needed –for example: “Every painting must have an underlying abstract idea as well as its more obvious subject.” So you have to be able to spot at least the area of the problem in the work before you can find his advice for fixing it.

This may be one reason why I thumb through the book when I’m resting my painting eyes — in the hopes that I’ll spot the precise concept that is missing in what I’m working on. But you are right — seeing the problem is often all that’s needed — and can often be the most difficult pursuit.

As for Hanneke’s paintings, I disagree that it’s merely the resolution of the problems of realistic presentation that makes them seem so, well, unproblematic. I think she is striving for a kind of joyful serenity and when she achieves it, there is no sense of a problem being solved. All that’s there is the serenity itself. At least that’s the sense I get and the reason that I found Kreutz’s comment that for viewer as well as painter “There must be a sense of problems being solved” not right. It’s that “being” — which involves an on-going state — that bothers me. Hanneke’s work “is.”

Birgit,

My obsessive painting really does have to do with a break in routine — I heartily recommend such breaks (especially if they come with vacation). I’m now going into my second month of the residency, with my 10 –12 hours of painting being done, and wondering if I might be getting burned out. I haven’t been in the studio for 4 days (and here I am on the computer rather than smooshing around linseed oil) and perhaps am putting off that crucial moment when I find out if a month is all I can take of this.

Enjoy your new perspective on perspective – and congrats on figuring out that the tool is less important than the concept and the work.

McFawn,

I’m a fairly gregarious person, but had to learn to limit my sociability. That lesson was hard but may have served me well ultimately. This residency has been an experiment in deprivation — the weather keeps me indoors, the lack of familiar chores keeps me in my studio, the materials at hand are all that I have. But I find that contrast is useful. I spend a lot of time alone, but when the social hours appear, I am ecstatic to be relieved of my own company.

Unlike Hawthorne (and yoursel), I can be a most boring companion to myself. I work better when I have some moments and some external things to push off of. So Kreutz is coming in handy. As is A and P.

Jay,

Like Steve, I find there’s something specific to postcards that goes beyond their size. Most landscape postcards are static. They don’t indicate movement or change of any sort. It’s probably a matter of design — important stuff either centered or directly in the sweet spot, naturalistic color — nothing to disturb your mind.

In a class once, a fellow student remarked that one of my paintings, if cropped by five inches on the right, would be a perfect postcard. He meant cropping would perfect the painting. I couldn’t stop myself from saying, with some sarcasm, that that’s exactly why I needed that extra five inches — the postcard vision is anathema to me.

That said, I have painted things that resemble postcards. But I tend to dismiss them once painted as unworthy. I like the rough (“sense of a problem being solved????) better.

June:

Could be that I haven’t had the requisite experiences for this discussion. To me a postcard tends to be a modest little affair that offers one side to an address and a personal message, and the other to a thematic visual. No pretensions beyond that – and chances are slim that anyone will liken any of my stuff as being ‘pretty as’. That said, I have seen post card images that reflect considerable talent on the part of their makers. It is said that behind every great post card stands a photographer looking to support a fine art habit. Renoir painted porcelain in his early days.

Malcolm Morley comes to mind. I’m looking at something of his called “New York Foldout” from 1972, which is a loving recreation of an accordion fold post card, likely bought in Times Square. In this painting he embraces the card as subject matter and also pays homage to the anonymous people who crafted the images.

Please excuse me if I appear to be riding a high horse: Steve could likely make me look good, striations and all. It’s just that my empathic side is trying to accommodate to the importance that this subject appears to possess.

Jay,

I didn’t mean to condemn all postcards by any means, and even the worst may have their place. What I meant by “postcard-style scenic photographs” were those that aim for some clichéd ideas of beauty, usually trying to cram everything in, from the foreground flowers to the distant mountains to the technicolor sunset. Even these can sometimes have merit, and, more in recent years, better ones are becoming available. The problem for me is not only with possible artistic compromises, but with the high frequency of such scenes in the culture and consequent lack of intrigue.

June,

I guess I’m not sure what “sense of problems being solved” should mean. I agree with your sense of Hanneke’s paintings. But part of what happens to me when viewing one is that I think, how could she make those grapes so luscious and real? I imagine the huge difficulty it would be for me to attempt it.