You must forgive me if my language about SE McLoughlin Boulevard is a bit crude. I refer to the Boulevard, actually a long strip of sleazy or derelict buildings, warehouses, and defunct businesses, as “the armpit of Portland.” It is fairly unsightly and often smelly.

McLoughlin Boulevard was originally US Route 99E, part of the major north-south Pacific Highway through Oregon’s Willamette Valley to California. US Route 99E had its heyday just after WWII until it was eclipsed by Interstate 5, finished in 1966. Thereafter, the Boulevard, demoted into Oregon Route 99E, declined as Portland grew. The decomposition of the Boulevard, helped along by the curbing of the highway which restricted access to businesses, was accompanied by its enclosure by warehouses and industrial compounds, all gone slightly to seed. The farmland and residences that had been behind its initial length of business ventures got pretty much decimated over the years by other kinds of cheaply built warehouses and small factories.

I first learned about McLoughlin Boulevard because, when we moved to Portland 18 years ago, the Pendleton Mill End fabric store was located along it. I would take the bus to the Mill End store; to return home, I had to cross 8 lanes of heartless traffic and wait for the return bus in front of The Odysseus, a saloon and strip joint. I avoided looking at the patrons — and they avoided looking at me!

It was that kind of street — an American urban highway that makes used car lots look good.

Still, however sleezy the street has become, it still speaks to my love of urban archeology and history. Jer and I have been investigating the Springwater Corridor bicycle/pedestrian trail that has a new bridge over SE McLoughlin. The Trail runs along Johnson Creek, a major urban creek wont to flood in the wet season and stink in the dry. But between the creek and the biking trail, there is a pretty wondrous set of scenes through the Portland cityscape, including McLoughlin Boulevard.

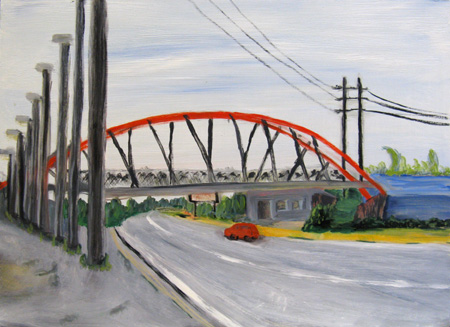

Springwater Trail over McLouglin, Oil on board, 18 x 24″

Springwater Trail over McLouglin, Oil on board, 18 x 24″

The advantage to the painter of this particular spot along McLoughlin Boulevard is that the Springwater Trail bridge goes over it at one of its less savory (and most fully itself) spots. The view from above is of the street, the traffic, the desolate buildings, working warehouses and small industrial buildings, an occasional private residence, lots of highway debris and macadam, Johnson Creek, bogs and wetlands surrounded by fencing, and the Oregon Liquor Control Board’s campus (which is a model of contemporary urban office architecture, including lawns, fountains, and winding drives.) All viewable from a quarter mile stretch of walking path.

So painting McLouglin, in many of its versions, became, over the last month or so, a passion with me.

McLouglin at Mid-day, Oil on canvas, 30 x 40″

McLouglin at Mid-day, Oil on canvas, 30 x 40″

I posted one of my McLoughlin photos earlier to A&P:

Ochoco Street from the Springwater Trail, Oil on board, 12 x 16″

Ochoco Street from the Springwater Trail, Oil on board, 12 x 16″

Ochoco is a side street, running perpendicular to McLouglin. It is where you gain street access to the Springwater Trail near the bridge.

McLouglin, Early Morning, Oil on board, 18 x 24

McLouglin, Early Morning, Oil on board, 18 x 24

McLouglin, 7AM at the Bog, oil on board, 12 x 16

McLouglin, 7AM at the Bog, oil on board, 12 x 16

McLouglin, Early Evening, Oil on canvas. 30 x 40″

McLouglin, Early Evening, Oil on canvas. 30 x 40″

Obviously I got caught up in that yellow paint that the two derelict buildings had in common. I made up stories about a traveling salesman with an excess of yellow paint on his hands; or, alternatively, an owner of both buildings who in 1952 was enthralled with the receipts from the tavern and the circular “entertainment” center, and upgraded them, using the peculiar ribbed roof (on the circular building) and the excessively yellow paint to signify his pride. Or perhaps it was more like 1964, when the street was already on its way down and business owners were desperate to bring in customers and the salesman sold the owner on the efficacy of yellow, how it would bring in hordes of excited customers.

But other tales can be told also. In 7 AM at the Bog, I was trying to recapture the moment (truthfully, not at 7 AM) when we parked alongside the derelict rectangular building, with its debris of a burned car in the parking lot. When I opened the car door, the sound of birds in the little triangular bog in the middle left of the painting overwhelmed the sounds of Boulevard traffic. Cattails grew behind the sagging fence and water fowl paddled through the reeds. I could only imagine how magical it must be on an early May morning and how astonishing life was, able to reconstitute itself in the most unlikely spots.

Amidst the warehouses and industrial buildings that can be seen from the trail are a couple of perfectly kempt and charming cottages, painted and spruced, with gardens in the rear. I saw a guy in a yellow ball cap wheeling a heap of grass to his compost heap behind his garden. I couldn’t fit him into the painting but he fit into the real scene perfectly. And up on the Trail itself a lone flutist wandered along the trail, making sweet sounds, like the birds, momentarily refuting the traffic noise. Almost a John Cage moment.

I think I could go back to McLoughlin and paint another 5 paintings without beginning to be bored. There’s something about the melange of history and lived existences that that view from the Trail gives to me. I can see a painting of the riparian zone being rehabilitated, just on the other side of the trail from the derelict rectangular building. I could paint the mysterious low brick building with no windows and a large parking lot, set into a grove of forbidding trees, across Johnson Creek from the riparian zone. I could even include the transient with his dog and rusty bike, peddling desultorily along the trail — maybe an erstwhile denizen of one of the yellow buildings when they were warm and alive.

In other words, these paintings are as much about my imaginative meanderings as they are about the place. And they are least about the paint and canvas, which are mere conveyances of the stories I hear in my mind.

So I’m wondering — Steve, in your abstracts, do you tell yourself stories? And Jay, that view through the window, all your slighly unfocused foam excavations and the chains within chains — what stories do they tell? Melanie, are the stories in the medieval scenes you love what attract you to them? I make up stories about Birgit’s paths, of course, and even her mud scenes are anecdotal. What place do stories, a medium based on time, have to do with canvas and paint, a medium based on a single sweeping moment, anyway?

June,

Making up stories! What a wonderful thing to do. And, you do like geology, archeology, history.

Exploring your boulevard together with you reminds me of the industrial landscape along a canal in my hometown. I drew it and then carved it into linoleum. It was exhibited as part of my high school show. In New Jersey, to satisfy Karl’s interest in railroads, the family explored a defunct railroad yard with a turntable.

The Bowery in NYC in the sixties was pretty derelict. So were parts of Harlem a while ago. How long will it take for your boulevard to reinvent itself as a desirable neigborhood?

You have gotten good at doing cars! I love the blue truck. My favorite among your paintings is the Springwater Trail over McLouglin.

Birgit,

I have a feeling that McLoughlin might be the next artists’ nesting place — all those derelict warehouses, just waiting for some painters to take over. And once the artists are there — well, there goes the neighborhood…

The real problem is that the Boulevard was built solely for automobile traffic and is very unfriendly for everyone else. Rehabbing would be a challenge. But then, Portland is rehabbing things I never imagined could be made clean and habitable. So I’ll keep an eye out.

I do love the “making up stories.” It sounds as if you do, too, and not just about paths through dunes.but even about the industrial landscape.

I remember going through the Bowery in the late 60’s in a Volkswagen bus that we felt could have had its tires removed while it was ostensibly moving — it was that slow. So if the bowery can be renovated, McLoughlin should be a breeze.

Thanks for checking in and making me think about other industrial landscapes.

June,

I too felt drawn to areas that fell into temporary disuse. I mourn the loss of the waterfront of my childhood where I roamed with my dog seeing only an occasional other person, an area that is now groomed and peopled by exercise-hungry citizens. I was fortunate to have that real estate as my playground, historically sandwiched between its use as submarine naval base and now, as North Sea resort.

I am glad to be in the company of an artist with an archeologist, historian, geologist mind.

I can relate to Volkswagen buses. Commuting across the Whitestone bridge on stormy days, mine felt like a sailboat.

June,

It’s interesting how you can use story on two levels: not only within individual pictures, but also through the series. I’m not sure if there’s a sequence to the paintings in this post, but one could imagine ordering them chronologically, or geographically (e.g.along your bike route), or according to how you came to know this area better.

I don’t usually think in terms of explicit stories, though the sense of story is very important to me, as I say in my statement about my ghost town project. Where those images become somewhat more abstract, such as the torn curtain in the window (see a previous post), they can suggest a story which could differ depending on the detail, from perhaps that of an individual shack inhabitant (last of the window sequence) to the rise and decay of a town.

Your mention of story as based on time resonates with Jay’s recent comment about time. In effect, story and time are as entangled as content and form, neither possible without the other. Thanks for helping me re-realize this.

I have a series underway that is overtly linked to story. I’ve found myself in a conversation with Moby Dick — a book I’d successfully avoided for decades, finally read out of guilt, and am now captivated by (especially the much disdained Cetology chapters). There are two main challenges associated with the series. One is the format, the pieces are all 12-inch square, so keeping the composition from falling into a bull’s-eye is an ongoing challenge. The other is to keep the pieces relevant to the book without falling too overtly into illustration.

And I do usually start with some greater or lesser verbal unit – not usually an entire Great Work of Western Literature, but usually a word, or a quotation. Words are very bossy, there is a limit to the nuances that can be explored without veering into ridiculousness. I find the limitation helpful – things that are so open-ended that they can be anything tend to end up being not much at all.

Steve,

In fact, I was thinking of your ghost towns as I was writing this post. They seem loaded with tales — and yet are perfect compositions in themselves. Not as abstract as your later work, but I have very strong memories of them

Time, that beast with the sickle, is hard to stop; immersing oneself in it might be one way to deal with it. But I’m always bemused by artists who can actually stop it with an image or poem.

Melanie,

I sometimes find my titles in quotations — and even my meanings. But I seldom begin a work of art with a word or quote — and to begin with Moby Dick — well, that sure doesn’t lack ambition. And I shudder at the square format — I think for me it could become a black hole into which I would fall every time. I like your comment about words being “bossy.” That’s perfect.

I’m thinking of the book I’ve avoided reading — Joyce’s “Ulysses.” I may have to wait until I’m grown up to try to deal with it.

By the way, I met Jane Davila last evening, who raved about your Moby Dick art. When might we get a chance to see it here on A&P?

June — Yikes.

1nd

I’m so glad you’ve had an opportunity to meet Jane. She is one of the kindest and most generous persons I’ve ever known. (Her whole family is as well — apples not rolling far from trees and all that). I know she was very much looking forward to meeting you IRL (in real life).

2st

I don’t have decent pictures of the MD pieces. I have a semi-fancy digital camera that I am having a very hard time getting comfortable with. The MD pieces have a lot of contrast and some shimmer — they’re mostly black and white (some are very, very white) and shades of gray, with a little red and gold thrown in for Symbolic Import — and I’m having such a horrible time trying to tame distortion and exposure that I usually leave practice sessions for days that start out bad and couldn’t possibly get any worse. Then there’s that scary cascade of technology: get the pictures from the camera to the computer and from the computer to the web. If ever I can master this newfangled machine, I’d be happy to share, but for the moment I don’t think my Medieval heart is quite up to it (and I don’t have readily at hand the kind of pre-teen for whom “histogram” is “intuitive”).

3th

Early in every term, I shock my students with my list of Sacred Cows of Literature that I can’t abide. At the the top of list are Woolf, Joyce, and Dickens. They find it very freeing. It sounds like you’ve had a lovely and fulfilling life thus far sans Joyce. There’s no reason it couldn’t go on that way.

Ah, Melanie, you are reassuring. I have mostly mastered my guilts about “Ulysses,” but once in a while, they crop up again. In my youth I did read “Moby Dick,” but don’t ask me what it said (insert snort).

Now Dickens, though, is lots lots lots easier than Melville — I mean, he writes plots. And he has a great moral sense that shocks students who are accustomed to cool irony. It was always fun to read aloud the chapter in Bleak House where he shoves the body of the young street sweeper (who dies of typhoid) under the noses of the aristocracy “Dead, my lords and ladies. And dying thus around you, every day.” Well, the original goes on much longer…

Woolf I dip into once in a while, again. I still like “A Room of One’s Own” (which has another peroration I loved to read aloud).

As for photographing your work — well, breaking it into smaller parts helps. If you learn to offload from your camera (and that’s not too hard), you’ll feel so empowered the next step won’t be as difficult. And “histograms” I leave to the professionals. I just use the automatic changes in Photoshop — and if they turn all the reds into blues, I Undo and play with the little manual lever for dark and light. Oh and Jay taught me a wonderful trick about the distortion caused by the lens bending, which I invariably get when I’m photographing rectangles. For that I will be eternally grateful — or at least for the next ten years.

I think you don’t dare think of everything you don’t know all at once. That way lies paralysis. Which reminds me of John Barth’s riff on trying to leave home. He gets stuck in a bus station, after he has asked the clerk where he can go for $47.52 (I’ve made up that amount). He can’t figure out whether to go to Athens or Cleveland or Columbus or Cincinnati, or whether to go anywhere at all. So he sits, struck motionless by indecision, until rescued by a kindly passerby (who is, of course, central to the plot, although don’t ask me how….)

And indeed, I liked Jane a lot. Wish I could have spent more time with her.

June:

How much do you want for McLoughlin at Midday? Along with Melanie’s pieces that’s one whale of a work of art.

There’s something storytelling about my map paintings. Any connector has a tale to tell. That gloaming image presents a feeling for me; a cozy busy light set against pervasive blues.

I know that I would make a lousy cartoonist as action sequences don’t come readily to mind. Maybe that’s why I feel as I do about the linkage theme – a way around a creative block.

June: I am taken by the various positions of the yellow building in your sequence.

My favorite is also “McLoughlin at Midday”, and its strong red/yellow/blue relationships.

On the other hand,”Street from the Springwater Trail” is also my favorite, with it’s neutrals and earth colors. I could see how both of these palettes have lots of potential for future paintings of the area.

I also like the last painting, in that I really feel the light hitting the yellow building and the building to its right.

and, not incidentally, I think the bare trees in Street from the Springwater Trail and (especially) in McLouglin, Early Evening are wonderfully vibrant.

June,

I sense something wonderfully simple: I am who I am and this is my world and I will act.

Thanks.

Thanks, everyone, for the feedback on the paintings. And the ideas! Jay, your Gloaming (which I see you continue to explore) set up some notions for me.

Stories, being made up of words, are generally linear — in the way that Melanie explains so clearly in Steve’s post. But something like the instant of vision of a painting or photograph might put you smack in the middle of a story but you have to make up the rest. The Gloaming photos are interesting not just because of their visual qualities, but because we all have perhaps had moments of voyeurism, evenings when we spy into windows before the curtains are drawn. Likewise the muddle that SE McLoughlin presents — the tidy cottage between the cement warehouses next to the derelict bar beside the 8 lanes of indifferent traffic — this plunks me down in the middle of a story, one that I have to make up with nothing but visual clues to go on.

June:

My apologies: I discussed your comment in the Gloaming post without answering you directly.

McLoughlin represents a set of historical confluences that is quite common in Pa. where we grew up.

There are some spots in my hometown – log houses, wide spots that were market squares – that resonate. One of my favorites is Rt.230 as it crosses the Swatara Creek. There you will find an old grain mill that was powered by an adjacent canal that served other mills down the way and was likely linked into the Union Canal. Up the hill is a housing development that replaced one, designed by Louis Kahn during WWII and across the road a bungalow that was home to a soothsayer. Running alongside the canal is an old railroad that once connected Middletown and Hershey, but now hosts the occasional tourist train. Stand by the mill and one is in the Harrisburg metro area with its upriver progression of rusted industry; cross the bridge and one is immediately in the farm country of Lancaster County which finds its greatest expression down among the Amish. Unfortunately this is more to be written about than painted.