As Steve noted not long ago, perception — how, as well as what, we see and record — is prime territory for this group. Some weeks ago I wrote about painting in the desert, the Great Basin to be more precise, and, even more specifically, the Amargosa Plain just outside of Death Valley.

After having spent 6 weeks in the desert, perceiving and painting, mostly plein air, I am now back in Portland reading about desert perception in William L. Fox’s The Void, the Grid, and the Sign.

Fox has spent most of his life in and around a variety of deserts and back-of-nowhere lands, but in The Void he’s primarily concerned with the Great Basin, that large space between the Rockies and the Sierras, where water flows in, but never out, where there is no river coursing to the sea. He says that outside of Afghanistan, this area contains the most mountain ranges (316) in the world, but there are also 90 basins, places where what little water exists is captured between ranges and sinks or evaporates. The best known of these basins is perhaps Death Valley, although that lies outside Fox’s attention. The place I was painting, the Amargosa Plain, is also just outside his wide-ranging travels. However, much of what he says is apropos of the Amargosa and Death Valley.

Death Valley at the Beatty Cut-off, March, 2009

Fox’s interest is in the intersection of geography (and some geology), cartography, personal experience, human perception (of land voids such as the basin and range) and art. He’s a poet, and the first third of The Void, the Grid, and the Sign revolves around Michael Heizer’s City, the enormous earthwork begun in about 1970 and premised to be finished by about 2010.

Fox’s description, found on his website, of the basin and range area is better than any I could create: “The Great Basin, my home desert, encourages … recursive thoughts. Covering almost all of Nevada and western Utah, it is a deeply repetitive landscape of arid basins and high ranges that betrays the cycles of earth, fire, and water underlying it. The entire region continues to swell, uplifted from underneath and pushing apart Reno and Salt Lake City at opposite ends of the Basin. Nevada alone carries three hundred and sixteen mountain ranges, some of them more than thirteen thousand feet in elevation, all separated from each other by valleys that can run a hundred miles long by twenty wide. The basins and ranges tend roughly north by south, massive wrinkles reflecting how the North American plate overrides the Pacific one. The bones of the land are naked here, and so is the syntax of the poetry.

“No water runs out of the Great Basin, all of it falling inward either to sink beneath the ground or to evaporate. Forming its western rim is the two-mile-high Sierra Nevada, an escarpment of granite that casts a deep rain shadow over almost the entire Basin. This is the largest, highest, and coldest desert in the contiguous United States. Because the air is so devoid of humidity there is little blurring of ridges thirty and forty miles away, confounding our sense of distance. Because the spectrum of color in the vegetation is so narrow, our expectations of atmospheric perspective, of a shift in color from a warm foreground to cool background, are distorted likewise.

“The ground at our feet and the distant mountains are all that we see. Nowhere is there a familiar tree or building against which we can measure ourselves. The cognitive dissonance is severe. We don’t know where we are. Traditional wisdom about being lost in the wilderness—follow water downstream until you reach civilization—does not often work here. Follow convention and you are likely to end up stranded in the middle of an alkali flat.

“The only way to understand the enormous space of the Great Basin is to invest time in your experience of it. Slowly your eyes will adjust to the extended reach of vision, and your ears become accustomed to hearing only the wind and your heartbeat. You will learn to read your way around, cutting across the grain of the land instead of following it in order to find your bearings.”

Prior to going to Nevada, I had a vague notion of the basin and range country from having traversed it on route 50, perhaps 40 years before, being astonished at its desolation and at the highway, cutting across basin after basin, rising slowly to the top of inclines, where it would slop wildly down steep backsides, to cross the next basin.

This is a view of a small California basin, the Panamint. The photo was taken from a small unnamed range that we had been traversing in the car; it looks back toward the big Panamint Range (the west wall of Death Valley), which is beyond the top of the photo. The photo has been enhanced a bit to show the road we had just traveled, moving from right center, reappearing to go off center left after crossing the saline flats. The photo may give some indication of the kind of territory that Fox describes and that I tried to paint.

Fox is interested in cartography, how people perceive and map land, and more particularly, how they map apparent voids. Americans, starting with Jefferson and taking cues from much earlier civilizations, map in grids, so John Fremont mapped the Great Basin, disregarding its natural formations and placing it with the rest of the grid that the US was forming. (Other cultures, such as the Australian Aborigines, map in very different ways, through stories and spiritual places, and even city slickers in 21st century America will map the distance from here to the nearest Peets Coffee Shop by time ( 25 minutes) rather than gridded space (15 blocks directly north),

Grids can be comforting, but strangely at odds with what one attempts to paint in the desert. Painting without much middle ground, and without much to focus on, can have strange effects on the painter’s psyche.

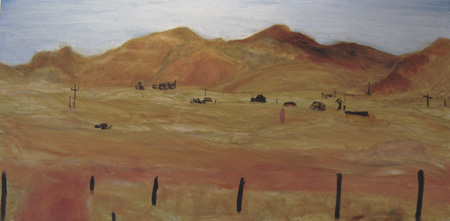

This is one view of the ghost town, Rhyolite, from a point south of the Red Barn, where I had my studio for those six weeks. The dots here and there in the center of the photo below the hills are what remains of the town. In its heyday, it had gridded streets, the tracks of which still can be found, as well as three railroad lines, and the usual array of post office, banks, a two-story school, saloons, and whorehouses, all placed on a grid. Just southwest of the ghost town is the sculpture area known as the Goldwell Open Air Museum, about which I wrote earlier. And southeast of Rhyolite is Ladd Mountain, now sculpted on its southern flank by a vat leach mine.

When I painted this scene (plein air) the first time, I was flummoxed by its randomness. Even when looking with my own eyes rather than through the flattening and distortion caused by the camera, the scene had no focus, no way to get hold of it. Here’s one discarded attempt at a plein air work of the subject:

It tooka number of weeks before I found the only spot around where the scene could make sense:

Rhyolite and Sculptures Panorama, 18 x 36″, oil on board

Only on a curve in the paved road going to the ghost town (marked by a big asphalt patch on the right side), can you see that the mountains, Ladd on the right, Busch Peak behind, and Sutherland (and Bonanza Hill) to the left formed a 3-sided wall. The town sat within these hills and looked out over the Amargosa Plain (alternatively called the Amargosa Desert), where that “wretched trickle” known as the Amargosa River sinks. [Digression alert: the Amargosa Plain is not legitimately a “playa”, because its water does not totally sink in its depression. A slight decline leads the existing water down to the end of the Funeral Mountains where it finds further slight declines around the end of the mountain and into a further declination that leads it to below sea level to Death Valley].

One of my earlierst paintings of the Amargosa Plain didn’t capture the void. It’s not a bad painting, but it isn’t the desert that I was confronted with, even though I was painting plein air. My brain simply couldn’t see the void in front of me:

Amargosa Playa 1, 12 x 16″ , oil on board

I painted that desert straight on at least 3 times and obliquely, a large number of other times. The oblique approach was definitely easier, because the mountains gave a place to go with the brush:

Funeral Mountains, Early Morning, 18 x 24″, oil on board

The middle ground is still lacking, so the mountains, which are perhaps 15 miles away to the west, look much closer, but at least they are there; and there’s a road, a sign, that leads one to know what is being depicted.

Perhaps the most successful painting of the void I’ve managed thus far was very late in my stay in Nevada. It is directly down the Amargosa Plain (desert/playa) in front of the Red Barn. It was painted in late afternoon, when the slight haze that the unseen river causes to rise over the ground surfaces gets played with by the sunlight:

The Amargosa Playa 3, 18 x 34, oil on board

The Plain isn’t fully empty at its southern end. A “pinch” allows the Amargosa to work its way between two mountain ranges before it turns west. So in some lights (like this one at 3 PM in mid-March) there is some edge to the void of the desert.

I have a canvas painting that presents the perspective in a different way; In Aereality Fox describes a variation of this form from an earlier painting The painting was found on an excavated wall at Catalhoyuk, Anatolia (Turkey): “This ‘volcano painting’ a panoramic view done around 6200 BC, shows the town in planimetric (a plan view, as if seen from straight above) and the then active Hasan Dag volcano, its twin summits sixty miles away reaching 10,672 feet, in elevation (in profile, as if seen from a horizontal view)…. there are no hills nearby Catalhoyuk, and athough the residents apparently climbed up the volcano to obtain obsidian, the town was effectively invisible from that distance… why make this composite image in plan and profile…. this is more than a map, but a highly mediated and thus expressive aerial view of the world.”

It is this “highly mediated and … expressive view” of the Amargosa plain, with a plan (aerial view) as well as a horizontal one from the Red Barn Studio, which I am still reworking. In other paintings, I managed to capture the grids with telephone poles and desert tracks, and even the signs, with speed limits on metallic boards and billboards. The rocks of the mountains have bold layers of folds and geologic structures and chemicals that made them explicable in paint. But the void is harder. And (therefore?) somewhat more interesting. And I swear, I read Fox’s description of the somewhat older art work after I painted the unfinished but blocked out plab/horizon version I’m now working on. I’m hoping to somehow do other versions of that Amargosa void, working the question of perspectives.

I would also say that Fox himself finds it difficult to discuss the void — mostly he discusses its edges, either by driving, hiking, climbing, or flying above them. Rocks and mountains make stops and points of reference; only artists working on the ocean, or someone like Michael Heizer, can make the void fully expressive.

Incidentally, Fox’s discussion of Heizer’s City, in The Void, the Grid and the Sign, is the best I’ve seen anywhere about this reclusive artist’s work. I’m hoping that when City opens (Dia: Beacon says 2010; right now it’s totally closed to the public) that I can spend some time there. Heizer seems particularly aware of the void he faces; he says City is not “in a place; it is place.” From Fox’s description, I can believe it.

June,

As usual, your post is full of ideas to follow up on. I will be digesting for weeks, at the least.

William Fox sounds fascinating, I’ll definitely be following up on him. Do you have and recommend Aereality? And speaking of books, you must read John McPhee’s Basin and Range, if you haven’t already. Great writing, great geology, quite relevant to your work.

I’m very interested in the dealing with the disappearing middle ground and the void. That can happen here, in fact this weekend I was driving in spots somewhat similar to basin and range topography–though with more water, having rainfall intermediate between the Amargosa and back East.

The plan-profile concept is intriguing (and reminiscent of recently-discussed Hockney-perspective), but I found that there is significant controversy regarding the “volcano map” from Çatalhöyük, which some think is not a map at all (see here, here, and here). I’m particularly interested in this because I’m writing about an artist, Sara Mast, whose work incorporates map elements from early sites in Turkey. Anyway, very looking forward to your expressive view in progress. Getting up high, as in your viewpoint in The Amargosa Playa 3, somewhat captures both aspects, giving a large middle ground. But of course that’s a different experience than looking from the plain.

A related problem I was thinking about, during that driving, was representing that huge void, the sky. Even when it’s a large proportion of the image, one doesn’t get the feeling of it arcing over you and all the way around.

More anon.

To me, ‘space’ shows up most strongly in paintings 3, 4 and 5 where it is filled with mist. Mist provides a sense of continuity such as water does in the ocean. Does this mean that it is impossible to paint the void without filling it with something?

Looking at your pictures reminded me of Leslie Thomas. More than ten years ago she lived in Michigan, longing for the big sky back home in Utah. Moving back to Salt Lake City, she started painting the desert around her.

A confession: I have a phobia of naked mountains that so far, I have only encountered in Southern California. They remind me of biblical movies. I do like the desert vegetation.

Hi Steve,

I do recommend Aereality, although it sometimes repeats what’s in “The Void…” It was the first Fox I read and lead me to ordering three more. And McPhee/Basin and Range/ and our trip across US Route 50 are intertwined in my mind so thoroughly that I don’t know which came first. That said, I realized it was time to reread Basin and Range, so I’ve ordered it up. (Of course, I will read McPhee on anything, even Lacrosse, and rereading him has a pleasure all its own).

Sara Mast’s work is very interesting — I shall return to her site.

I fear that I myself am a bit confused about the void stuff and that that confusion became part of the post. Fox’s focus on Heizer’s “City” turns out to add to the problem, since City is so huge that it encompasses some large factor of the void. Not something one can do with paintings, although Fox mentions the Abstract Expressionists’ large canvases, as least in passing.

And of course, the middle ground problem is worsened when the normal middle ground becomes the entire background — take away the sky entirely and with the playa you can omit middle ground views.

Ah, it’s all very much too much for my wee brain at the moment. Yes indeed, the desert sky is yet another void, particularly during the day, with that blank mid-day sun. Fox’s book on LA, which I found less compelling, mentions the way the mist and the dust (not smog) interact in Los Angeles to make a perfect haze for movie makers. I remember seeing something of this in Wechsler, probably his book on Hockney.

Birgit,

Your comment made me realize that the point of the Void section of “The Void…” is about Heizer’s City, which apparently is trying, with great geometries and greater earthmoving and rearranging, to make the void present. But of course, he can only do it by filling the edges. Great conundrums that even Fox admits.

Your confession about naked mountains saddens me — I love them. They are far more interesting than the wash of green that goes on and on in my native Pennsylvania (or it’s equally boring wash of dirty gray in the winter). I like seeing the evidences of those tectonic forces. And I was stunned by the east side of the Sierras. As we drove back from Nevada, we followed them for a long way and at times, the highway would, for whatever reason, turn right toward them and there would be this massive, enormous, amazing granite wall, straight up, that you would be hurtling toward at 60 MPH. The clarity of the air made the granitic structure seem very close and at times I had the sense that we were simply going to squash like bugs against the enormous space.

Now that’s a different kind of “void” as I think of it. Anyway, you’ll have to spend some time with John McPhee and William Fox and you might grow to love the crazy folded pink and green and gray and black and white and granitic stoutness that the naked rocks give you.

June and Birgit:

Your reference to “naked” mountains hit a spot. Those mountains in Nevada are definitely naked and provocative as such. June, you may remember the logging museum in northern Pa. where one can see photographs of the hills shorn of cover, shaved, de-nuded. It is so good to see a forest reassert itself in that area and in the Grand Canyon of Pa.

And, June, please overcome your aversion to flying and take a flight out of L.A. for points East. No red eye as you really need to see the void from a perspective seven or eight miles up and hundreds of miles out. Anybody who reads the Sky Mall catalog while that multi-hued vastness is shouting at you, has wood for eyeballs.

June,

This isn’t quite on track, but talk of Heizer and near and far ground reminded me of a passage in Varnedoe’s Mellon lectures on abstract art I was just reading:

See images of Double Negative here.

Steve,

The Varnadoe quote is very much in line with what Fox is tracking (and it may be Varnadoe I was thinking about earlier). In fact, Fox says that at times City looks like “the traces of an ancient civilization.” Here’s Fox on Heizer’s “City.”

“‘City’ is a structure built in the middle ground of a desert valley and as such there is no competition for our attention. Like the poet Wallace Steven’s proverbial ‘Jar in Tennessee,’ it orders all around it — or rather, enables us to do so, though as a work of art it holds a few caveats for us. Viewing ‘city’ is not as simple as looking at telephone poles or a barn on a farm. If, for example, you don’t know the size of the sculpture, it can be very confusing: the valley looks looks much smaller than it really is; your walking time up to the leading edge of the site seems to take forever. ….’City’ doesn’t look what we expect of art; it’s too big and geometrical, too unexpectedly both a part of and apart from the land in which it sits.”

“In the just-before-dawn light, the absence framed by “City” is much more palpable than in the strong unfiltered daylight of the hight desert. Last year Heizer made two new “negative paintings.,” empty square and circular steel frames. They need to be watched at for a while before it becomes apparent that the frames are not the art. They are devices to focus our attention on what’s not there. the spaces enclosed by the steel. That’s also one aspect of “City”. The geometrical lines and solids of the complexes are more than just a frame, are indeed objects to be looked at and considered, but they also define and articulate an empty space, an absence, that is an essential component of the sculpture.

“I say “watched” instead of “looked at” because the active elapsing of time in the process of consideration is important. We don’t just look at, or even into, a void, though that’s how we usually “frame” the activity with words. We actively engage it. We first look at it, then into, then all around it to see if we can find its edges, not least of all so we don’t fall into it. Our vision penetrates the empty space, and our eyes attempt to focus, an automatic and uncontrollable reaction of the nervous system that is doomed to failure, there being nothing our binocular gaze can coordinate upon in space. All of this takes a few seconds before either we begin to move away from what has become an unsettling experience, or we settle down to see what happens.”

I (June) quote at such length because I think that’s what was happening to me and what I was doing for those six solitary weeks, although I had no words for it — a kind of articulation void.

Later Fox says “City” is the “first exhibit in my contention that the void is an imaginative construct necessary for us to place ourselves in the world. We need a perceptual frontier over which we can peer in order to imagine that there is still an unoccupied space to go into, at least in our imaginations if not in reality. We need a space where the grid fails to cocoon us …. We need a space where our customoary perceptual protocols fail, and we find ourselves in the presence of some other, some nonhuman sensibility”… Heizer has made the void visible by the only means we know, surrounding it by perceptible form and making geometry and nature coextensive.”

I(June) am susceptible to this idea of the void if only because of the mystery that it contains. It’s a mystery we face with a blank canvas, although there at least we can hurry up and obliterate the void. In certain medical tests, they test inner ear functioning by boxing the patient in with no visual cues; all the cues for standing upright have to taken from gravity as it acts on ears and on proprioceptive (body) sensations. I find David’s paintings actions upon a void, in part because I cannot imagine, until I see them manifest, how he will parse that void of the canvas. A video of the process, set up within wall without visual cues, would be fascinating.

Jay,

I have seen that landscape (many years ago), but from too far above, with no cues as to what I was looking at. What I really want to see it from is a Piper Cub.

It isn’t flying I object to — it’s airline protocol and ugliness. I can’t imagine why anyone would spend any time taking a commercial flight except in matters of life and death (and maybe paying the rent). The experience in the terminal and seats is horrible beyond anything my regular life presents me with, so I avoid it.

June,

I’m re-reading Seeing is Forgetting… on Robert Irwin, and was reminded that at a critical point in his career–he’d given up his studio, sold his things–he started driving out in the desert and noticed the kinds of presences he felt in certain places. Perceptual, not spiritual ones.

Steve, — brilliant connection. I have pulled out my Weschler’s Irwin and am rereading parts of it and am thinking I need to be 25 and feisty again.

Sometimes I feel like that fellow in George Eliot’s “MiddleMarch” who keeps saying vaguely, “ah yes, went into all that at one time.” My memory is the pits so I’m totally delighted you reminded me.

We are having some remodeling done to the house and I’m going to have to pull my fabric/sewing storage area apart and stash it elsewhere. I have a roll of wool batting — about, oh, 2 feet across — a lot of batting, as well as tons of fabric, much of it blanks in cotton and silk. Now it seems to me that the underlying premise of the desert vista is that it gives you nowhere to stop your eyes except the somewhere that might be a horizon, if only the mist would allow you to see it. If I were 25 (or even 50) I would consider buying a 12 foot ladder and using all my fabric to turn my 400 square feet of studio into a space where nowhere stops the eye, although there is much to see everywhere and yet not much to see. All the narration would be within and with whatever was around, behind, moving the materials; the meaning would have to come from the environment and from within, not from the art, although the art would be the precipitating factor.

Anyone around Portland who is young enough to hoist 12 foot ladders and daft enough to want to try something? Ah, I thought not……….. But there’s still that roll of batting and the clerestory windows that would shine through it, mucking up the greens behind……

June,

Inspired by you, driving up, or rather, being driven, to Northern Michigan, I trained my eyes to perceive the 3-dimensionality of the landscape passing by.

Yesterday, I sketch the dunes. It was fun, distorting what I saw to put more on the page than was in my binocular vision, laterally.