This touches lightly upon some of our prior discussions.

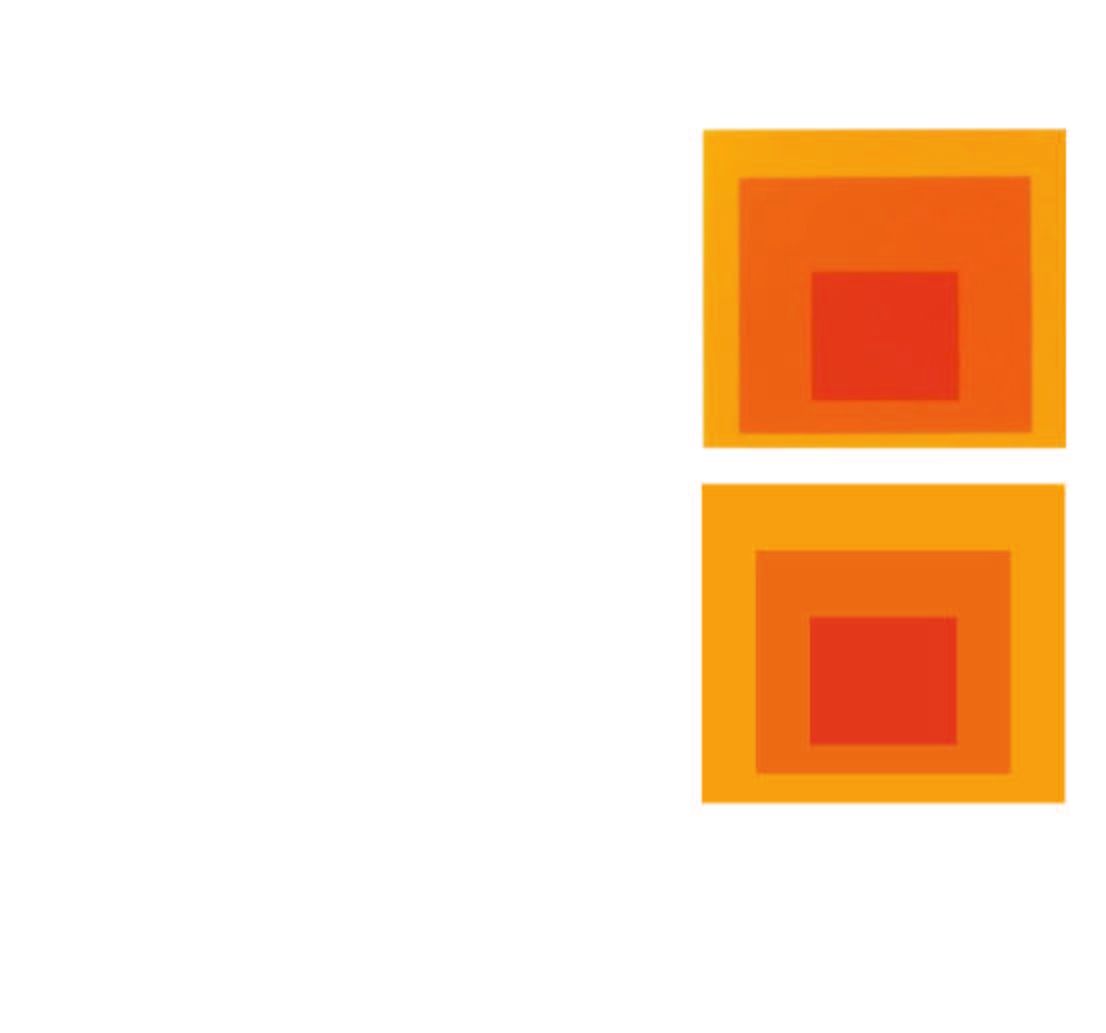

I wanted to compare an Albers “Homage To The Square” iteration to a similar, but mechanical version as rendered in Adobe Illustrator.

The Albers image was chosen because it appears that he was trying for a gradation in a single hue. I lifted from a site where it is being offered as a poster. Therefore, it may be chromatically inaccurate – but what hey.

I created a replica of the outer limits and the innermost rectilinear shape in their respective relationships. I then sampled the poster for the colors of the outermost and innermost elements and then blended the elements, calling for one interim shape.

Obviously the interim shape is at issue. The Illustrator version splits the difference in size between inner and outer, as it does the color. Not so with Albers who made the interim more imposing in size and saturation, and to my eye it looks a whole lot better.

Correction: Albers may have been trying to mediate between two hues.

Jay,

The Albers version is dramatic while the Illustrator version reminds me of interior decoration.

Jay,

Did you happen to choose that example because it came up first among the thousands in the series in a Google image search?

I guess the top one is the Albers. In any case, a little detecting (I use Color Cop, a free program, for Windows only) on the Red-Blue-Green components shows that the middle hue differs in having a larger green component in the lower version. The inner and outer colors also vary mainly by the amount of green, and are different hues, at least technically (subjective definitions of hue vary quite a bit).

Jay,

Comparing the pictures again, in the upper image, the red center projects forward while in the lower image, it recedes in my perception,

Jay, your use of the term “hue” needs clarifying — See the Wiki Definition of HUE The red in the Albers painting looks close to Cad red Light or about 10 degrees (a little orangish) on the HSB color wheel. The outer band is probably a cad yellow orange/or deep and, around 40 degrees on the color wheel. I’d bet the middle orange is halfway between.

Color theory really is rocket science so I won’t get into it. For a painter the HSB/HSL color space is much more convenient for visualizing color.

Imagine the color wheel starting at Red at 0 degrees (almost Cad red medium – I think Liquitex does something with this BTW) — Opposite, at 180 degrees is Cyan

The rest of the colors, Yellow = 60 deg, Green is 120, Blue is 240, Magenta is 300. So yellow is “yellow” with no tint (orange or green) right around cad yellow medium/light. A warm yellow is around 50 deg, a greenish one around 65-70 degrees.

Adding white reduces the saturation while maintaining the brightmess.

Adding black maintains the saturation while reducing the brightness

In practice, burnt umber is close to a dark orange (40 deg) and mixed with a ultramarine blue (or similar about 220-240 deg) you can get a neutral grey. In other words, one can use the color wheel to visualize what will happen when any two colors are mixed (in their pure states) This was essentially one of the things Albers was doing.

FWIW, the center red area looks to be about half the size of the orange square, this makes the orange-red area ratio 3 to 1

More:

The geometery of Albers can get esoteric. The diagram is worked up around the Google source image – conclusions are pixel fuzzy but indicate that Albers was good with a ruler and a compass

Steve:

It happened to be the only image where it appeared that he was splitting a difference in such a manner. Why chosen? Because it was there.

George:

Have we met? Seems Albers knew his straight edge. Interestingly a shot of him at work would suggest that he didn’t use tape, but instead freehanded the edges.

David:

I have a question if you’re following this…if Albers’ “Homage” series makes you think of one composer, then to whom would you relate Rothko in his late work? I’m thinking ambient composers here for Rothko, but I can’t come up with anyone whose work would embody the crisp and geospiritual nature of Albers.

Jay, I doubt we’ve met, but I’ve followed Angela’s paintings for awhile.

George,

Thanks for the link on the geometric construction for the nested squares. However, I’m skeptical that this is more than coincidence in this case (some look for the golden section everywhere). The diagram doesn’t really make sense to me. And in fact, it looks like Albers used a variety of different relationships for his Homage series. See, for example, the collection at the Albers Foundation. Albers was very sensitive to the effects of the relative areas of different colors, and I would expect him to vary this in his paintings to get the desired effect, depending on the hues used, rather than slavishly follow a fixed construction.

However, I haven’t found anything at all definitive on this, and I’d love to hear of any information about the construction process.

Steve,

I’ll agree it’s open to debate. I made the diagram I linked, it seemed fairly obvious on first glance. Alber’s actual working process, I don’t really know but his whole program seems fairly stilted and boring, so it’s not unlikely that he worked the geometry every now and then.

What was more interesting to was the nearly perfectly even spacing (HSB) of the three colors. This was done in the old days and done by eye. FWIW, in the 90’s I managed a team of programmers making color-correction and printing software, I know more than I’ll ever need and tend to find Albers boring.

Make it any color that looks good — almost always works

George,

Thanks, I very much appreciate your input. It is interesting to see how Albers’ subjective choices relate to numerical color systems. But I also tire of them before long. I would find them more interesting if they were accompanied by some notes about the effect he was seeking (though perhaps that defeats his purpose). And doubtless I would appreciate Albers better if I were a painter learning my colors, rather than a photographer more or less at the mercy of the world.

Rigorous color printing is still hard, I can imagine the difficulties a decade ago.

Not knowing if Albers began with a nested construct of rectangles to which he added colors, or chose colors and then pushed them into mutual relationships.

Seems like I would have done a few sketches before proceeding. And, George, I agree with your assessment as I dealt with an “Homage” on a daily basis at the museum, and very few people showed much of an interest in it. Moreover, to paraphrase a quote, it seems to me that color theory is often to an artist as ornithology is to a bird.

There are certain geometrical arrangements which are pleasing in their pictorial structure – say their appearance as doorways or hallways. Additionally, these geometrical constructs can be used to produce whole number and golden section ratios between the various color areas – the eye sorts this out for itself as pleasing. I think once Albers made the geometric set ups, he then worked with the color according to his theories,

Today we have Photoshop. What once was quite difficult, or took time consuming trial and error can be accomplished easily using Photoshops simple drawing tools. The paintings by artists like Noland, Albers, Vasarely, Riley and even Al Held were difficult to construct and color more than 20 years ago. Today one can fool around with “stripe paintings” on the computer creating endless variations in an afternoon.

As a tool, drawing programs allow the painter to create simple mockups and quickly test out the visual effects of various color palettes. I doubt that it will make a better painting but sometimes you can solve a painting problem on the computer

This also touches on Steve’s comments about the difficulty in achieving accurate color output. Anything capable of producing or recording color has what is called a “color gamut” which is by definition the contained range of the producible or reproducible colors. Paint has a color gamut, so do inks and the two are closer to one another than the gamut of film, or digital recording and displaying devices. The cyan blue on a monitor RGB 0,255,255 is not reproducible with most inks, it is lighter and more saturated. By contrast, a pthalo cyan blue is not reproducible on a display device, it is too dark and saturated. In fact RGB 0,255,255 only means something on a particular display or recording device and is not the same on a different device (it’s possible to calibrate printers, scanners and displays to smooth over the rough spots) Because the artist typically is daisy chaining several input and output devices together, this process can get very complicated very fast.

In the end, what matters is how the final output looks, not how you get there.

I just obtained my ‘Interaction of Color’ and I look forward to studying it.

A couple of notes: Josef Albers, in his Homage to the Square paintings, did not mix color. He made the compositions using unmixed colors available in tubes, from various manufacturors. He applied the colors with a palette knife. The colors he used are usually listed on the back of the painting.

See http://www.minusspace.com/tag/josef-albers/

Here’s a quote from that link:

“Throughout the series, also known as the Adobe paintings, Albers used a similar composition with varying colour combinations, applying paint unmixed, directly from the tube onto white primed hardboard.”

I don’t know if the screen prints he made were based on the paintings, or developed as separate images.

In all these images a central issue is the spatial reading…does the red advance or recede? Which depends on whether you read the red as a transparent plane over the orange, or the orange as a ‘translucent’ sheet over the red. There is not a ‘correct’ reading.

Also, the term hue refers to thew redness/yellowness/blueness of a color, and is fairly objective. Even in very grayed (low saturated colors) there is general agreement in observers about which appears redder, or greener, or whatever. BUT…only when they are presented on neutral fields for comparison. When surrounded by other colors they are very subject to being changed in appearance.

Bruce:

O.K. I went back to Albers images with the in-the-tube in mind and can see where he may have done just that. But what was his point? To collect tubes of paint? Did it have a didactic function?

His use of only unmixed tube colors…..why? Certainly related to his asking his students to work with found color paper samples…never having them mix colors. BUT…why? Go figure…..I don’t have an easy answer.

Equally intriguing is that he applied the color with a palette knife. With scrupulous care. I think one must see the paintings to begin to understand this.

Check out this amazing illusion based on Albers-style color influences.