The phrase, “Sloppy Craft”, the title of a recent panel discussion and a forthcoming exhibition at Portland’s Contemporary Crafts Museum, had to be checked out. Whatever could it mean? How could the Contemporary Crafts Museum have been drawn into featuring sloppiness? What kind of provocation was intended by the title? What are the implications of honoring such a concept as sloppy craft for art as well as craft? Tell me more, tell me more.

A bit of background: when I was working textiles, I regularly engaged in a “discussion” with quilters (some traditional, some contemporary) about whether the stitching work done on my textiles ( specifically in construction and quilting) should strive for perfection. I always maintained that my goal was “competence.” My attention was entirely on the image and impact (on, I maintained, the art). The craft was there only to hold it together and/or to add to the art. Hence my seams were not necessarily straight and the back of the art was decent but not flawless (I didn’t bury my threads, for example, simply tidied them). I used the quilting stitches as part of the design, which meant that they were generally not even in length and that they were heavy in places and light in others; this can make the quilted art hang wonkily, requiring heroic measures to make it perform well.

This is an example of a old piece of mine that I claim has “competent” craft:

Sophie, Emerging, 84 x 73″, 2002, Materials: hand-painted cotton, canvas, silk, stretch-polyester, felt. Methods: hand- painted-and-dyed, airbrushed and commercial fabrics. Machine stitched.

Sophie, Emerging, 84 x 73″, 2002, Materials: hand-painted cotton, canvas, silk, stretch-polyester, felt. Methods: hand- painted-and-dyed, airbrushed and commercial fabrics. Machine stitched.

Sophie Emerging, Detail

Sophie Emerging, Detail

I violated all kinds of quilting craft standards here — you can probably see that the center has been lightly stitched while around it the stitching is quite heavy. I mixed materials so wildly that my friends burst into laughter when they heard that I hoped the canvas, silk, light-weight cotton, and stretch fabrics would hang flat on exhibit. I did exhibit it, with aluminum rods inserted top and bottom, one of which got lost so the piece buckled badly (the uneven stitching, not to mention the range of fabrics, will do that). At one point I almost took it out of an exhibit because it showed up so badly next to the much finer craft that it hung beside. We replaced the rod, which helped a little, although it always did look like sloppy craft (albeit not “sloppy craft.”)

I didn’t reform much in the following years, although I did throw away the stretch fabrics in my collection. But I continued to have discussions about how “fine” the craft which gets put into art should be — how much it should conform to finely crafted quilts, for example, that regularly win large awards at national quilt shows. Is competence sufficient in quilted/stitched textile art?

Which brings me to the panel discussion “Sloppy Craft”. “Sloppy craft” is described by craft theorist Glenn Adamson as the “unkempt” product of a “post-disciplinary craft education.” The panel here in Portland featured The Art Institute of Chicago’s Professor Anne Wilson (Fibers and Materiality), Wilson’s former student Josh Faught (now teaching Fibers at the University of Oregon), Nan Curtis (professor and head of many departments at the Pacific Northwest College of Art), local artist Jessica Jackson Hutchins, and Namita Gupta Wiggers, the head curator of the Contemporary Crafts Museum. The discussion was held in the Commons at the Pacific Northwest College of Art, which in itself startled me — it seemed an unlikely venue for the old Contemporary Crafts Museum. While the CCM has recently moved downtown to the heart of Portland’s art scene and has had some staff shake-ups and financial troubles, they were traditionally a quiet force for High Craft in Portland. Whereas, the College of Art (PNCA) has a highly contemporary, conceptually-based, post-modern orientation.

All the panelists have had wide exposure in exhibits and reviews and writing about their respective areas and seem clear about their own artistic journeys.

Josh Faught, according to his instructor at Chicago Anne Wilson, knows his craft (fibers — weaving, crochet, knitting) inside and out, and is currently working in sculptural mode:

Josh Faught, Untitled, 2008 crocheted hemp and garden trellis

Jessica Jackson Hutchins, the youngest panel member, also does sculptural work.

Jessica Jackson Hutchins Convivium, 2008, table, linen, paper maché and ceramic, 52.75 x 56.75 x 53.75 inches

Nan Curtis is an installation artist (she did 52 “street signs” along 12th Ave, two blocks away from my house, signs which were posted on telephone poles, like rock band flyers, but having official government looking typeface and material). She has installed complete versions of her home (“Homebody,” Manuel Izquierdo gallery, 1998), and many other conceptual installations of that sort.

Nan Curtis, Role Model #1: She has always served him well 2005

Nan Curtis, Role Model #1: She has always served him well 2005

digital photograph on gator board 22.25″ x 29.75″

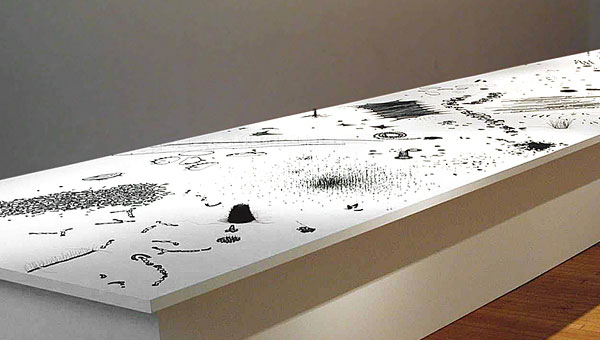

Anne Wilson too works in installation mode, although her imagery seems less rough to me:

Anne Wilson, Topologies*, 2002

Namita Wiggers continues to make her imprint on the Contemporary Crafts Museum (she oversaw its transition to its highly visible downtown location) and has become a force on the Portland Art Scene. She writes and interviews extensively, is a regular participant in the national crafts scene, and brings exhibits of the highest quality to the CCM.

So, what did this diverse group of artists, three who have roots in traditional fine crafts, have to say about craft and art.

Anne Wilson was perhaps the most interesting interlocutor: she said that “sloppy” was really a sound bite, irresistible once uttered aloud. “Sloppy” indicates intentionality, which she didn’t think was the case with the art she was describing. She would favor terms like “informal” “casual” or “raw” rather than “sloppy” to describe contemporary art that has some base in traditional crafts. Most interestingly, she observed that artists now seem to “take on” crafting only when they need it.

Traditionally, a craftsperson would spend years polishing her craft, working at the highest level until she was so good she could let it go; she would have behind her all the knowledge needed to return to “fineness” if the art required it. To some extent Josh Faught fits that mold. He self-identified as a Fibers Major at Chicago, while his fellow students in fibers always made clear they were “Fibers-and-…” “…and performance,” “…and installation,” “…and assemblage,” “…and collage.” But at some point Faught let go of the fine work of Fiber Craft and turned to rawer work.

Another example of the fine craftsperson turning to raw work after years of exquisitely fine craft is Peter Voulkos.

Peter Voulkos died in 2002 but a look at his biography shows a continuing movement through the highest worlds of craft, then into the fine art world. His craft won him honors over and over again. And his art gained him access to the most formidable museums of high art.

Peter Voulkos died in 2002 but a look at his biography shows a continuing movement through the highest worlds of craft, then into the fine art world. His craft won him honors over and over again. And his art gained him access to the most formidable museums of high art.

That model, learning the craft inside and out and then letting yourself go, however, has changed to “learning on need” which means that you might teach yourself how to sew a straight seam but can put off learning to sew curves (not to mention French seams). And you might marry stretch/polyester to silk, which violates a lot of traditional sewing standards, for a number of reasons.

Beyond the Need to Know response of current students were a couple of other aspects of “sloppy craft.” One was the recycling of materials — trash art, one might call it. It’s everywhere these days, at least in Portland, and no one bats an eye at exhibits with “wedding dresses” made from plastic bags picked up on the streets. The other aspect of this kind of casual crafting is that it appears most often in assemblages and collage. Assemblages and collage have clear ancestors, dating back to Picasso, through Rauschenberg and arte povera and are seen and made by thousands of people who may not even think of themselves as artists.

Two exhibits, Unmonumental at the New Museum in New York and From Trash to Spectacle: Materiality in Contemporary Art Production were specifically referenced as examples of what has happened in the national scene when informal craft became firmly entrenched in the world of art. These kinds of works — ready-mades, gritty street junk, messy — are contrasted to the highly commercial and polished art of say, Jeff Koons’ Balloon Dog or Takashi Murakami’s Vuitton bags, which are “finely crafted brands” (the phrase used by Kathryn Hixson at the School of the art Institute of Chicago in her discussion of Trash to Spectacle).

Anne Wilson made another comment at the panel discussion that stuck with me: she said that so-called sloppy art required the highest level of attention to detail — everything counted, because the meaning of the art is so central. No lapses into mumbling or side-trips into irrelevant detail could be allowed to interfere with the meaning of the piece. Her example was of a student working with clay and fabric, who wanted to indicate the spilling out of fluid materials from the hardness of the clay. But the student closed the ends of her fabric spillages with stitching and that attention to a “craft” detail stopped the sense of things spilling and in some sense stopped the art from succeeding.

One audience member at the panel noted that because we are now mostly knowledge workers, with few workers in the general public who craft anything besides digital artifacts, fine craft may be accessible only to aficionados of specific fine crafts. In my experience, people are piqued by color and image and like to see stitching, but really can’t see or don’t care if the stitches are tiny or big. They are aware only the overall force of the wall-hung or sculptural material.

In fine craft, attention must be paid to every detail of the crafting — stitches must be buried into the interior of the quilt; wood grains must enhance the flow of the entire piece and be carved and sanded to perfection. That’s the “need” of fine craft, focusing attention on the material itself. But the “need” of contemporary fine art, according to Arthur Danto, philosopher of aesthetics, is to pay full and whole attention to the meaning of the work; every detail must express the meaning of the whole.

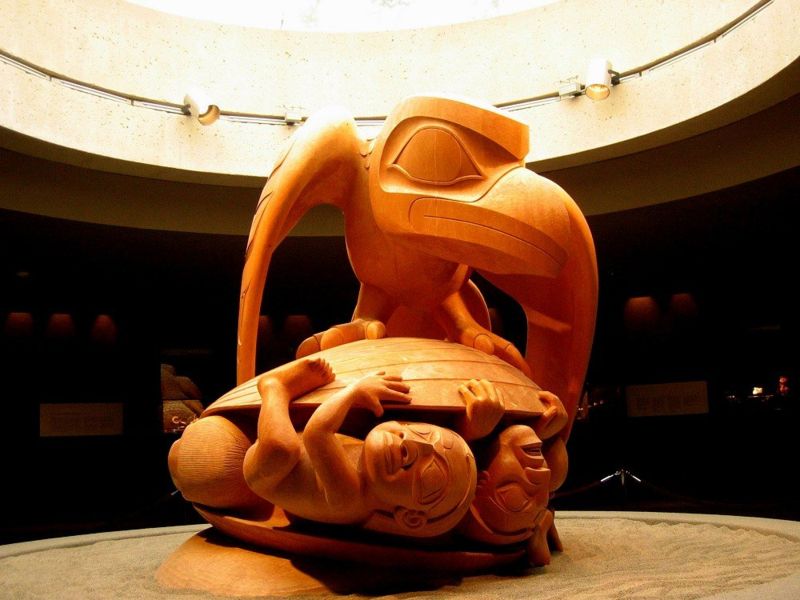

I would add another difference between high art and high craft which is that art tends to be individually identified: Anne Wilson is the artist, even though she may work with a large crew. But much of fine craft is community-identified: the Gees Bend quilts, the totems of the Pacific Northwest indigenous peoples; African masks. The craft may be formed by a single individual, but it arises from the standards of a community. Sometimes at the highest level, the two overlap, so we may know Bill Reid’s name as one who sculpts items such as were crafted by Pacific Northwest indigenous peoples. But much of finely crafted work is anonymous, perhaps done communally. And the standards by which it is judged are set by a community of craftpersons, those who know exactly how many stitches there are in that particular inch, just by looking at it.

As Kathryn Hixson comments, trashy and fine art and craft may represent continuums rather than opposites (so I’m in the running with my middling concept of “competent”.) I am fond of Bill Reid’s sculpture, finely crafted of course, which seems to exemplify in its imagery some of the difficulties this kind of discussion is always running in to:

Bill Reid, Raven and the First Men, 1980

Bill Reid, Raven and the First Men, 1980

Reid’s humans, working to escape the clam shell, may exemplify the struggle to understand as well as produce, and to produce out of understanding, that forms the most singular element of our current state of art.

As a kind of PS, I would venture to say that Jay’s work fits perfectly into the informal craft mode, while Hanneke’s seems to harken back to the traditional crafting of fine art. And I just heard about a class in figure drawing at a local university, which runs for 3 quarters. The first quarter features only the bones of the human figure; measuring and drawing bones is all that students do. The second quarter moves on to muscles (with more measuring); the third allows for some flesh — always measured. The mind boggles, but there are at least 15 students in the class who are opting for this model of traditional high art crafting.

And this just in: in today’s NY Times, Denis Dutton,a professor of the philosophy of art at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand and the author of “The Art Instinct: Beauty, Pleasure and Human Evolution.” takes on the whole question of permanency in crafting and art.

* And as a further PS, I thought it might be worthwhile to present some official textual presentation that accompanied Anne Wilson’s Topologies exhibit, as a sample of the kind of thinking brought forth by her work in “informal” crafting.

project statement from Anne Wilson’s Topologies

While our society faces a growing fragmentation and specialization that seems at times to alienate us all, we have also started to view our world as a series of integrated, even entangled networks. One way we can begin to understand this contradictory state is as a matrix of field phenomena – repetitive patterns of texture, growth, turbulence, sound, light, etc., within a given system or space.

— Douglas Garofalo, architect

Textiles, in their expandable and accumulative structure, can be seen as metaphors for such a matrix. In this new project, the webs and networks of found black lace are deconstructed to create large horizontal topographies, ‘physical drawings’ that are both complicated and delicate. This work is a constantly unfolding process of close observation, dissection, and recreation. The structural characteristics of lace are understood by unraveling threads; following the impetus to remake, mesh structures are also reconstructed through crochet and netting. The computer affords another means of close observation: lace fragments are scanned, filtered, and printed out as paper images. These computer-mediated digital prints are then re-materialized by hand stitching and are placed in relationship to the found and re-made lace in the topography.

The logic of organization within the project is based on the concept of like kinds. Never exactly repeating, areas of proximity are formed on the basis of the structural and visual characteristics of likeness. There is both unity and formlessness as parts coalesce, separate, and collide.

As a physical material, black lace has diverse cultural implications in relation to sexuality, death, and gender. These aspects of material context are embedded in the work, yet are not the dominant voice. This project references many things simultaneously: relationships between systems of materiality (textile networks) and systems of immateriality (Internet and the web); microscopic, specimen-like images of biology and the internal body; and macro views of urban sprawl – systems of organization of city structures, interdependent and/or parasitic, processes of expansion. No single theme or position is privileged over another.

This project is large in scale, but the specific configuration of installation is flexible, the size determined by the space at each venue as the project travels. The horizontal architectural support is created on site — a white painted wood platform.

exhibition history

Topologies (3-5.02), 2002

Installation, “2002 Biennial Exhibition,” Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, March 7 – May 26, 2002

Lace, thread, cloth, pins, painted wood support, 31 inches high x 74 inches wide x 18 feet long (overall dimension) Topologies (9-12.02), 2002

Installation, “Anne Wilson: Unfoldings,” Sandra and David Bakalar Gallery, MassArt, Boston, September 4 – December 7, 2002

Lace, thread, cloth, pins, painted wood support, 31 inches high x 74 inches wide x 36 feet long (overall dimension) Topologies (4-5.03), 2003

Installation, “Anne Wilson: Unfoldings,” University Art Gallery,San Diego State University, April 7 – May 7, 2003

Lace, thread, cloth, pins, painted wood support, 31 inches high x 74 inches wide x 36 feet long (overall dimension) Topologies (1-4.04), 2004

Installation, “Perspectives 140: Anne Wilson,” Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, January 16 – April 4, 2004

Lace, thread, cloth, pins, painted wood support, 31 inches high x 74 inches wide x 36 feet long (overall dimension) Topologies (11.07 – 2.08), 2007

Installation, “Out of the Ordinary,” Victoria & Albert Museum, London, November 13, 2007 – February 17, 2008

Lace, thread, cloth, pins, painted wood support, 31 inches high x 74 inches wide x 20 feet long (overall dimension)

A provocative phrase, that — “sloppy craft” sends craftspeople ballistic — and some collectors, too.

Excellent article, June!

Very thought provoking.

I know some of the “sloppiness” in my work is a rebellion against machine made copies of handcraft (think sewing machines that do “perfect” embroidery, as well as the perfection of stitches desired by machine quilters with stitch regulators). I believe that the irregularity of my work is the human factor made visible and is uniquely mine.

I am also guilty of learning what I need to know to achieve a desired result without spending months or years learning everything there is to know about that technique.

I’m not too happy about the term “sloppy” as is it has so many negative connotations. I think I would prefer something more calculated like “raw” “irregular”.

I’ll be mulling this over for a while.

Wonderful article. I subscribe to this mentality since it is the way I was taught in school. One art teacher would not let us abstract a figure until we could draw it in proper proportion. I feel I reached the technical pinnacle many years ago in traditional quilting. Recently a judge’s comments on a thread painted piece were transcribed as “distoriated stitching.” I’m wearing that as a badge of courage that she had no idea I had never intended for the stitching to be even and merely used it as another element of design.

Namita Wiggers also blogged about another in her series of panels and lectures about craft’s placein contemporary western society. This one is about Garth Clark’s lecture called:

“How Envy Killed the Crafts Movement: An Autopsy in Two Parts.”

You can find Namita’s overview at

http://www.craftcouncil.org/conference09/?p=1329

And the lecture is available as a Podcast as well as an on-demand book from the Contemporary Crafts Museum in Portland: http://www.museumofcontemporarycraft.org/salesgallery_publications.php

Thanks for this very interesting explanation, June. I think I get it!!

Very interesting essay, June! As usual, well written and well researched. I am particularly interested in the ‘sloppy craft’ movement because I have seen it used as excuse for not doing things the ‘right’ way- in order, with intent, and with meaning. (see any local indie craft show). Thanks for your efforts at clearing this out for us!

I can be ‘neat’ and ‘well crafted’ with the very best of them A high standard of finish has always been a matter of course in my work, until I got to where I began working in what is now my ‘Tracks’ series. I’d never have thought of it as sloppy and yet, it is, although I don’t like that term – but the rawness is integral to the series concept and so quite deliberate. To work this way at first was not easy but absolutely essential, and I had to think and concentrate on not tidying up, not neatening off the slightest thread, and absolutely not unpicking anything, and then burning it. http://www.alisonschwabe.com

A fascinating post with some very interesting links. Thanks June.

June,

Your post made me think of my grandmothers, one crocheted lace, the other a virtuoso on the sewing machine and last week’s Eureka about my own journey.

My distant past: At a high school in Germany, I learned fancy hand stitching and machine sewing.

My recent past: During the long evening of a winter vacation, I handmade a wall hanging showing a landscape with crude shapes symbolic for events and beings in my life. I saw myself on the path to some sort of textile adventure when I bought ‘The Embroidery Stitch Bible’ by Betty Barnden because it was such beautiful little book.

Last year: I got sidetracked into painting water from photographs.

Last month: Inspired by a local artist, I painted large shapes vaguely signifying landscape motifs. While I liked my imitation of the artist’s colors, overall my picture did not appeal to me. Am I reduced to painting from my photograph?

This week: After carefully painting parts of a wooden dock, a duck and their reflections from a photograph, I filled in the streaming water with colors that pleased me without much attention to detail. Standing back, I felt a void. My photograph puts me into a ‘meditative’ state, but that did not happen with my painting. Thus, I erased the water by overpainting it. I am now studying the water patterns by drawing them with a pencil. After having sufficiently learned the details of its changing colors, I will attempt to reproduce them in color.

Using this comment as a sort of diary, inspired by your post, I write that patience and close observation of detail will be an important part of my art/craft endeavor in the near future.

Sandy and Alison,

“Sloppy Craft” is an unfortunate phrase — Given the word’s meaning, it sounds as if the work is sloppy intentionally, when it’s meaning that is intentional — the work and material are more incidental, as Alison puts it, to a deliberate concept.

I just read an article on Urs Fischer, showing at the New Museum in NY, who works at the size and in sort of the frame of Jeff Koons, but whose work is “sloppy.” The curator of next year’s Whitney says “Urs sloppiness is absolutely perfect sloppiness…. It’s almost the platonic ideal of sloppiness. That’s the interesting part.” Urs’s work is in that continuum that Hixson talked about in conjunction with the Chicago exhibit Spectacle/Trash — he has a crew of constructors who work up his models on the computer and then send them to China to be made. But they must be made “sloppy,” perfectly sloppy.

Birgit,

Not much was made by the panel (as I remember it) of the imperative of “process” in contemporary art — but some of the most acclaimed contemporary art deals with process — like the guy who set up a kitchen in the museum, cooked dinner, and invited spectators to join him in eating it.

But the DYI movement, I think, is not just about “learning at the time of need” but also about process — and tactility — getting the hands into the threads and paint and knitting wool.

It’s also about people living longer and having many different lives to live through — so your process sounds like mine and the kind of process that we urge our (grand)children to work through — “try things out when you are young.” Well, now, we are into the “try things out” mode, only at the other end of the age spectrum. Alas, by the time the world figures out that grandma Moses wasn’t the only elder who took up art seriously, we’ll probably be long gone. Or maybe that isn’t an “alas.” Maybe, it’s the process, and only the process, that’s so exciting.

By the way, why did you paint water with watercolor. Watercolor is maddeningly difficult. I actually did some terrific water in oils using both big and little brushes to form the surface texture. The rest of the painting stank, but the water was [she said humbly] terrific. I recommend you go back to oils, but then, I’m prejudiced.

June,

This post got me contemplating. I make mosaics, and there’s a lot of discussion among mosaic artists advocating it as “fine art” rather than craft. Mosaic was a craft for most of its history from what I can tell–an artist would design the mosaic, and mosaicists would actually choose the tesserae and apply it. But in traditional craft, mosaic seems an outlier, and the closest category is “mixed media,” or “ceramics,” or “glass”–maybe at the Society of American Mosaic Artists conference there would be conversations about “perfectly cut” pieces or fabulous grouting–I haven’t been to one, so I don’t know what would get the most appreciation, but I’ve heard that “conceptual” pieces have been winning the major prizes at the conference. Some mosaics are all about a perfectly flat surface, and mine are many levels, a rough terrain, so perhaps that is “sloppy craft”.

Caveat: I did not attend the lecture. I am responding to the post and the comments and do not intend to do more than ponder.

“sloppy craft” – is this an oxymoron? Coming up through the “fine arts” in my formal education, I was taught that respect for tools and materials is the basis of all good work in the arts. That good craftsmanship is simply that: a respect for tools, materials and the uses to which end results will be put.

In my less formal “needlearts training” I was taught that the degree of craftsmanship required was determined by the end use of the item. A chair must function to support the weight of the user, a container must hold its contents well, etc.

It is interesting to me that Peter Voulkos was mentioned: A well respected potter, he became, over the course of his career, a “ceramic artist”. He, along with Rudy Autio, are credited with the perceptual transformation of clay as a utility craft to ceramics as an art form.

It is notable that as their work progressed it became less concerned with the standards associated with “fine craft” and much more immediate – an improvement, IMO. But “sloppy”? I think we have a language issue here.

OTOH, the use of the word got my attention .

Laura,

Indeed, it is a language issue and the phrase was, as the panelists said upfront, intended and used (not by them) to get your attention.

I was more interested in the change from craft as something to be apprenticed to and mastered and only then transformed to art to craft as what you picked up when you needed it, and only that which served the immediate need.

Anne Wilson attempted to line up the various reasons why “informal” craft had suddenly become so popular with young artists, but her emphasis was not on the “informal” part but the materiality itself, which she said was what her students felt a lack of in the digital age.

I like your phrase: a “Respect for tools and materials.” I suspect that the more one works with particular tools and materials, the more respect one gains for those who are truly masters of their crafts — even while, like myself, the person who is just learning decides to stop learning the craft when it’s adequate and pursue the meaning instead.

Thanks for checking in.

I saw Anne Wilson’s 2002 installation at MassArt in Boston and was quite struck by it. Like a lot of artists whose work I find particularly interesting, I don’t get the chance to see it as often as I should.

Your “official textual” material is interesting — both apt and overly academic at the same time. It touches on subjects that interest me such as maps and networks. But I’ve read so much stuff on the use of themes in art that I can’t help but rolling my eyes at how cliche it sounds. I think I could do better myself, but maybe not that much better.

Her sensibility in her installations seems to be more that of a picture-maker or environment-maker than that of an object maker. And so I think a different kind of standard might apply: it has to hang together visually but it doesn’t have to do so physically. Things in a drawing can look like their going to fall apart but we don’t want a table or a building to look that way. (Or maybe we do, as the popularity of Frank Gehry seems to indicate.)

Sloppy craft rocks! We’ve been looking at “perfect” art for so long and there are so many beautiful and thought provoking art out there that is “imperfect” to the snobs eye and beautiful to us regular folks. I find that I am more creative when I can just work and not try to be so perfect and the results are much better and the journey is more fun.

There is some very shoddy crafting being done and it will fall apart before too long. Does anyone care? I want my pieces to last so I take as much care as I can to make them sturdy and well-constructed. Loose but tight, sort of.

But craft means something as a word, so is it crafted or …

What about all the “sloppy” paintings that started with impressionism and are not done yet? Numerous famous artists threw out fineness a long time ago and we are used to it now.

The digital age makes things too precise..some of us are going analog with our art, so to speak!

Ma, you are quite right about the word “craft” — crafted means made — which might simply be opposed to “manufactured.” I think the analogy to the sloppy impressionists is a good one.

June:

It may indeed be in the terminology: we have “slip-shod”, “slap happy”, “slob”, “sloppy”. So in craft it may be a choice: excel or “S-L”.

June:

I’ve got to go back over your post here. For some reason I was unable to pay it sufficient attention when submitted.

Did catch the link to Arthur Danto and immediately became opinionated about his thesis. More on this.

Jay, I’m slowly getting back to the virtual, thoughtful world — read your recent post on the chains. I’m still somewhat behind and foggy from the various medical stuff, but hope to be more responsive on A&P soon. I am putting up my latest panorama on southeastmain — this week is the week.

How could you help but be opinionated about Arthur Danto — he loves it so (opinionated opinions, I mean).

sloppy craft is being taught in schools and celebrated. Because of this we are producing a generation of crap. Most artists are graduating with minimal skill and an unformed imagination. People who want to be taught the skills to create fine art shouldn’t go to an art school but a trades school!