Pursuing my two favorite motifs, water and the anatomy of movement, I started making composites, extracting from one image and pasting onto another.

Showing the first version of this composite to a mentor, he questioned me about shadows.

a multi-disciplinary dialog

Pursuing my two favorite motifs, water and the anatomy of movement, I started making composites, extracting from one image and pasting onto another.

Showing the first version of this composite to a mentor, he questioned me about shadows.

You must forgive me if my language about SE McLoughlin Boulevard is a bit crude. I refer to the Boulevard, actually a long strip of sleazy or derelict buildings, warehouses, and defunct businesses, as “the armpit of Portland.” It is fairly unsightly and often smelly.

McLoughlin Boulevard was originally US Route 99E, part of the major north-south Pacific Highway through Oregon’s Willamette Valley to California. US Route 99E had its heyday just after WWII until it was eclipsed by Interstate 5, finished in 1966. Thereafter, the Boulevard, demoted into Oregon Route 99E, declined as Portland grew. The decomposition of the Boulevard, helped along by the curbing of the highway which restricted access to businesses, was accompanied by its enclosure by warehouses and industrial compounds, all gone slightly to seed. The farmland and residences that had been behind its initial length of business ventures got pretty much decimated over the years by other kinds of cheaply built warehouses and small factories.

I first learned about McLoughlin Boulevard because, when we moved to Portland 18 years ago, the Pendleton Mill End fabric store was located along it. I would take the bus to the Mill End store; to return home, I had to cross 8 lanes of heartless traffic and wait for the return bus in front of The Odysseus, a saloon and strip joint. I avoided looking at the patrons — and they avoided looking at me!

It was that kind of street — an American urban highway that makes used car lots look good.

Still, however sleezy the street has become, it still speaks to my love of urban archeology and history. Jer and I have been investigating the Springwater Corridor bicycle/pedestrian trail that has a new bridge over SE McLoughlin. The Trail runs along Johnson Creek, a major urban creek wont to flood in the wet season and stink in the dry. But between the creek and the biking trail, there is a pretty wondrous set of scenes through the Portland cityscape, including McLoughlin Boulevard.

Springwater Trail over McLouglin, Oil on board, 18 x 24″

Springwater Trail over McLouglin, Oil on board, 18 x 24″

Architecture Students Present their designs at the Savannah College of Art and Design

Architecture Students Present their designs at the Savannah College of Art and Design

On the Ragged Cloth Cafe blog, I wrote about the nature of critiques, mostly summarizing James Elkins’ Why Art Cannot Be Taught; I won’t go into his ideas — you can read a summary on Ragged Cloth if you are interested — but I have been evolving my own thoughts on the subject.

Last Tuesday, in a painting class, the instructor failed to show. We were scheduled for a long critique session, and, being self-sufficient and interested in each other’s art, we continued with the critique ourselves. The critiques in this class had always been group affairs, ones in which the instructor led but did not direct the conversation. So we could easily emulate his processes.

Elkins’ speaks of critiques as fraught with dangers, having multiple ways to can go awry, and he loves the fascinating explications of human nature and thought in action which critiques provide (which is also why they are fraught with dangers).

Some of the danger, as I see it, lies in the fact that while the artist wants information that will help improve her work (and also is hoping to impress the viewers with her artistic abilities and insights), the “panelists” — students or professionals in the field — are almost always struggling to explain what they are seeing. If the panelists (in our case, the other students) are to be successful, they must have insights into the work they are looking at, and then find ways to articulate those insights so that the artist will benefit. It’s a struggle on both sides, since the artist has to be totally alert to the thoughts of the panelists — sorting out, when comments seem confused, whether the speaker are struggling to find her idea, struggling with expressing the idea, or struggling with explaining the idea in terms that will benefit the artist.

And when comments are not confused and the panelist clearly states an opinion or question or makes a comment, the artist has to sort out whether the comment comes out of a concern which the panelist has with his own work or obsession or whether it is truly applicable to the art that is being presented. Other kinds of interface problems can occur — the panelists may get off course and meander into digressions; they may find themselves hostile or overly sympathetic, and so forth.

All this is outside the sometimes awful experience of attack critiques, those legendary events that leave the artist a quivering heap of jelly. I think they arise not out of art or articulation or ideas, but an entirely different culture and one that I haven’t encountered.

Nevertheless, critiques, as I know them, are a substantial and important part of my art education.

In this critique, I limited myself to three works, a “straight” naive/realistic painting of a nearby street scene, a more complex and abstracted view of a warehouse area from above, and a semi-abstract “forest” scene.

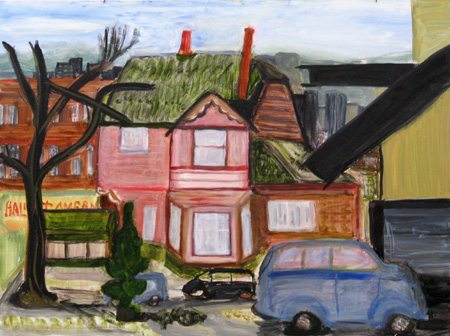

Hawthorne & SE 20th, Mid April, 12 x 16,” oil on board

McLoughlin Warehouse District, Mid April. 12 x 16,” oil on board

Forest Scene, mid-April, 12 x 16,” oil on board

I was interested in people’s responses to three very different kinds of paintings, all done within a couple weeks of one another. I was particularly interested in this group’s comments, because they are very articulate about what they see. I am somewhat intimidated by their ability to explain what they see, what they like, and how they read a canvas. So I am learning as I listen to them, not just about my art, but about talking about art in understandable ways.

The responses to the three pieces were that they enjoyed the corny street scene, that the colors in the warehouse piece were good (the reproduction here doesn’t do them justice) and that the composition in that one was excellent (they liked the water tower, just as they liked the old lady crossing 2oth Street), and finally that the last was puzzling, interesting, weird, Hansel-and-Gretel-ish,or maybe smelt of Hieronymous Bosch. At any rate, the last, for them, seemed to be coming out of some inner state, whereas the other two were evidences of external scenes. There were other comments but these are the ones that I remember most clearly.

But what the group really wanted to know was where I was going in terms of this last piece. Was this a direction I intended to pursue? What would I be painting next?

I talked for a while, and then realized that the the group consists primarily of abstracting landscape painters — people who take their references from landscape and then work those references into abstractions. Here’s David Trowbridge’s work. David is an accomplished artist, currently exhibiting in downtown Portland, whose work I admire. It is fairly representative of the working process and product of most of the group members.

David Trowbridge, Sheffield XI, acrylic and spray paint on plywood, 35.5 x 48″

So when I debriefed myself about the nature of the critique, I had to consider that the abstract attracted the panelist’s attention most because they themselves did art like that. And the questions about where I was going from there were both out of thinking this might be a new path for me, but also a function of knowing that the class was coming close to its conclusion. We were all going to have to decide “where we were going.” I did ask directly and firmly, at least twice at the conclusion of the session, what suggestions they would have for me. They had none.

So my question is, what kinds of critiques have you had that left you with interesting debriefings? Why were the critiques useful? What unanswered questions were there? Do you believe in critiques — if so, what are their limitations?

While reworking and sequencing my Winter Water project, I realized that, for a photographer as well as a physicist, snow, ice, and liquid are very distinct states of water, with distinct texture, tone, and shape. Perhaps because those photographs had no sky, I managed to completely forget about the vaporous state. Last Monday, however, I was vividly reminded of that glorious phase while biking through Yellowstone. Roads were clear but cars not yet allowed, so I had it almost to myself: only a half dozen other bikers all day, and a few service vehicles per hour. Fortunately I had a late start, so by the time I reached the Lower Falls it was well on in the afternoon. The westerly light left the falling water in shade while illuminating the mist.

This is dawn on the Colorado Plateau before I put my glasses on. This particular scene from my bag looks better that way.

I continue to get out and about in my Portland neighborhood, painting whatever resonates with my quirky instincts. I plant my easel on the sidewalk, set up my palette, and proceed to put color on board.

This activity invites community action: sideways glances, deliberate not-lookings, polite “may I see-s?” and full-fledged engagement in conversations.

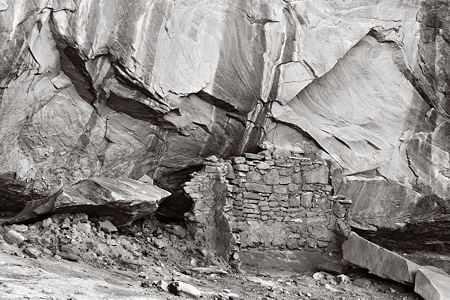

I’ve just returned from a trip to the Colorado Plateau, my third since getting my camera. The canyon and mesa landscape is amazing, but most of my interest lately has centered around the ancient remains of human habitation, and their relationship to the landscape. I’ve focused on the small settlements and structures, and haven’t even been to larger sites like Mesa Verde in many years. My reasons: the small ruins are not on maps, there are no crowds, and the hiking and searching for them is a large part of the enjoyment.