I have just joined Facebook (thanks, D.) and of course, instantly found a group dedicated to a textile artist’s focus: namely, texture.

The photos of “texture” on the group site were close-ups, both of quilted fabric and of objects that showed as textured. I started through my photos and quickly realized that deciding on what shows texture is not as easy as might be imagined. Here are some possibilities from my files.

The High Note, JOU, Computer images on Silk, quilted, 12 x 12″, 2008.

The upper layer (of computer-printed sheer fabric) is turned back to show under layer. Normally the sheer would fall over the entire piece, showing through as it does on the right bottom. This dropping of the sheer obscures much of the texture while at the same time, contradictorily, adds to it.

Vilhelm Hammershoi, Sunbeam (and various other titles), 1900, oil on canvas.

I was thinking of writing this post on Hammershoi, so I had lots of photos of his work easily accessible. He’s Danish, died at age 52 in 1916, was in Paris while the Impressionists were impressing people (he wasn’t, impressed, I mean), and shocked his contemporaries by not making paintings with stories, content, mytholgies, or “meaning.” Of course, we’ve added all those to his paintings since then.

Photo, Main Street in January, Portland Oregon, 2009

More often than not, we see texture, even if we know the thing we are looking at is flat, like those tree tops that look soft.

Vilhelm Hammershoi,Gentoft Lake, 1905, oil

Hammershoi’s techniques included using paint thinly, in layers, ala Vermeer. His work is near-abstract, although the images are clearly identifiable. He has been highly touted because of the flatness of his images, although his late paintings of city buildings in London have been less than positively reviewed — mostly, I suspect, because they use perspective so classically. But in the Gentoft Lake image the water has great texture, as do the doors in Sunbeam.

Charley Bierly, Little Pine Creek in Snow, photo, about 2005

JOU Little Pine in Snow, oil on board, 2008.

So texture isn’t just a matter of medium (as seen in the quilted piece, The High Note) or a kind of technique (as in my version of Little Pine Creek). It, like most art, is a matter of illusion. Even though we know the tips of the trees would lash rather than soothe and the hills are solid and stony, they still look soft.

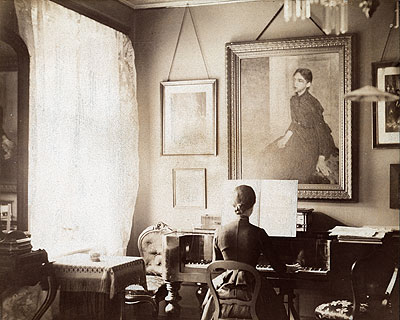

Photo of Vilhelm Hammershoi’s parents home in Copenhagen (portrait above piano is by Hammershoi, of his sister, who is most likely the pianist, also)

Vilhelm Hammershoi, Interior with Woman at Piano, Strandgade 30, 1901

Hammershoi gives us clear texture in the table cloth, the woman’s hair, even the butter (which has more goosh to it than can be seen in this internet version).

I’m still maundering about the question of texture in photos (and, necessarily, on the internet.) Shadows, hue changes, and recognition of objects seem to be the most immediate elements that cause us to “see” texture. More often than not, we see texture in almost all representational images, even if we know the real thing (the computer screen, the photograph, the painting) to be flat or relatively thus. Only in true abstraction is texture sometimes obliterated.

Clement Greenberg and the abstract expressionists knew that flatness was an essential of painted art. Greenberg said, ” The essence of Modernism lies… in the use of the characteristic methods of a discipline to criticize the discipline itself… What had to be exhibited and made explicit was that which was unique and irreducible not only in art in general but also in in each particular art.” ( Modernist Painting, 1961 ) He also said, “It has been established by now, it would seem, that the irreducibility of pictorial art consists in but two constitutive conventions or norms: flatness and the delimitation of flatness (After Abstract Expressionism, 1962).

We have come a long way from the ab exes and C.G., but we also, because of media explosions, see more and more in 2-dimensional imagery in which we insert our own sense of texture.

So I still haven’t resolved in my own mind what I should be looking for when I’m thinking about photographs of art that contain “texture.” Anybody have a brilliant (or even a generally interesting) thought on the subject?

PS: For more about Vilhelm Hammershoi, see also the Ragged Cloth Cafe recent post.

June,

Is the black bird part of the background textile or is it part of the overlying veil with the computer print-out?

Putting a transparent veil with texture over a work of art appears much more interesting than, what I believe, some artists did, namely obscuring some aspects of their painting with opaque cloth.

What is the function of a veil? Protection? Protection from the elements? These days, I arrive at work with a wind-burnt face – icy weather in Michigan. Protection from being spied on?

In your artwork, besides adding texture, the veil adds mystery.

About Vilhelm Hammershoi, I envy your colleague from Ragged Cloth Cafe for having seen his exhibition in London. I was tempted to go but never made it. His work is spell-binding.

But I don’t know whether I think of his minimalism of peaceful. I read, hopefully remembering correctly, that he was quite tyrannical in protecting the emptiness of his apartment. From what I remember his wife had to put up with a lot.

Birgit,

The bird along with the branches was printed on a hand-dyed silk sheer (the sheer is the overlay/veil). All the imagery is computer printed. The under-layment is a painting, printed from a digitized image, cropped, and stitched. Then I put the sheer with the bird and tree branches over the quilted printed painting.

The function of the veil, for me, was compositional. The painting, for whatever reason, didn’t have much impact directly printed and stitched. But with the birds overlaying it, I think it gives it a bit of mystery. It also fills a hole in the underpainting.

Here’s the URL for the piece as it looks with the overlay dropped properly, as it is currently being exhibited: http://southeastmain.wordpress.com/2008/12/12/new-focus-at-coos-art-museum/

As for Hammershoi, I think he and his wife has a rather fraught relationship — he refers to her genetic “madness” and another artist flees from their apartment to get away from her, but H. also rearranged all the furnishings of their space so he could paint what he wanted to without the interference of real life stuff. The apartment, while more sparse than might have been conventional at the time (but then the Danes do have great style), actually had more “stuff” in it than the paintings show.

I am fascinated by the doors, myself. He paints a lot of them. And the backs of the figures, too. The minimalism to me seems enigmatic (did I say peaceful? or was that elsewhere?) as do those doors. Some critics have found them claustrophobic — I assume those writers were from California. Having grown up in an old house and a large family, doors were very important to me, particularly as they could be closed.

June,

Computer-printing the tree really works. Painting it wouldn’t preserve the filligree effect of the bare branches. It looks great!

I have been starring at the Hammershoi. Like most people (?) my eyes are drawn to the window. It reminds me of windows on top of a door in a house that we lived a long time ago. I remember photographing it.

I am married to one of these Copenhagen minimalist. In his Manhattan apartment, there are only pictures in the bedroom. The walls of the living room are bare. It works, because the window looks out on the Hudson.

June,

I like the two-for-one of the veil over the quilted painting. I imagine it would work particularly well in a room with the window open, on a not too breezy day. It also reminds me a bit of Birgit’s superimposed photos.

In abstract art, I take “flat” to mean fairly even in texture, not totally texture-free. Thus the surface of Hamershoi’s lake or Bierly’s photographed hillsides can acquire a life as larger patches, which can have interesting shapes and relationships independent of their interior details. I like that, as one peruses such an artwork, one can have alternately, or even simultaneously, the realism and the abstraction of it.